Happy midweek everyone! Wow. We are already halfway through the week. Wow. Today is the last Wednesday and the last day of May. How time flies. How is 2023 going for you? I hope that the year has been kind to everyone. If not, I hope you will experience a reversal of fortune in the coming months. More importantly, I hope everyone is happy and healthy, in body, mind, and spirit.

As it is midweek, it is time for a fresh WWW Wednesday update, my first this year. WWW Wednesday is a bookish meme originally hosted by SAM@TAKING ON A WORLD OF WORDS. The mechanics for WWW Wednesday are quite simple, you just have to answer three questions:

- What are you currently reading?

- What have you finished reading?

- What will you read next?

What are you currently reading?

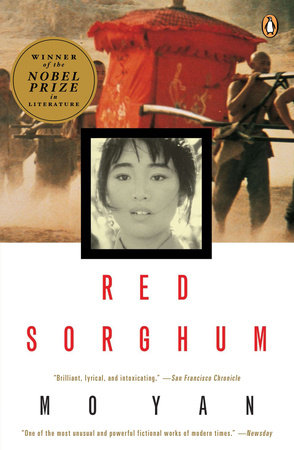

After spending two months immersing myself in the works of Japanese writers, I am now pivoting toward the rest of the Asian continent. I am very much looking forward to this journey for I have a lot of books in mind. One of these books is Nobel Laureate in Literature Mo Yan’s Red Sorghum. The novel is my first by Mo and is also part of my effort to expand further into the realm of Chinese literature, a part of the vast literary world I, unfortunately, have underexplored. Anyway, it is with this book that I am commencing my journey into Asian literature. The novel charted the story of the Shandong family between 1923 and 1976. It is rather bleak, at least in the two parts that I have completed. Death and violence permeated nearly every page of these two parts. The setting did not help as it was juxtaposed to seminal but violent historical events such as the Second Sino-Japanese War. I am midway through the book but I am hoping that this bleakness will slowly be replaced by one of hope.

What have you finished reading?

The dash to close my journey across Japanese literature was certainly mad as I was able to complete four books in the span of five days. The first of these five books was Nobel Laureate in Literature Kenzaburō Ōe’s Death by Water. Death by Water, while it was the first book by the 1994 Nobel Prize in Literature awardee that I acquired, was my fifth novel by Ōe. What held me back from reading the book was my apprehension to explore Ōe’s oeuvre. But my curiosity got the better of me and in little under three years, I have completed five of his books.

Interestingly, Death By Water is also the third consecutive novel by Ōe I read – after A Quiet Life and A Personal Matter – that qualified under the popular Japanese literary movement, I novel. I hoped it would be more like the first two novels by Ōe I read but this is still fine. At the heart of the story was Kogito Choko, or Kogii for short; he was the alter ego of the writer. The concern of the novel was Kogii’s pursuit to complete a novel he started decades ago involving his father’s death; his father drowned during a sudden flooding in their hometown in Shikoku. Ten years after the death of his mother, Kogii (he was already seventy years old) finally had the chance to complete it as he was given permission to open a stack of letters owned by his father but was kept off limits by their mother, and eventually his younger sister Asa. The novel is more about Ōe and discourses on his works form an integral part of the story. It does, somehow, remind me of a previous comment about writers placing themselves in their stories. It feels almost narcissistic. It does apply in this case but I guess it can be attributed to the rumblings of an aging man who wanted to reconcile his memories, his dreams, and his realities. The novel meandered although it did underscore some seminal and timely subjects. It was still a compelling read; Ōe’s works rarely are otherwise.

Speaking of the Nobel Prize in Literature, one name that has been repeatedly nominated for the award is Jun’ichirō Tanizaki. Unfortunately, he never got to win the award although he got close in 1964, a year before his death. Nobel laureate or not, it cannot be denied that Tanizaki has built one of the most extensive oeuvres within the realms of Japanese literature. It is no surprise that he is a writer that I am now looking forward to. Diary of a Mad Old Man, one of his last novels, is the fourth novel by Tanizaki I read.

The titular old man is 77-year-old Utsugi Tokosuke. He lived in Tokyo with his wife and son Jokichi and Jokichi’s wife, Satsuko. The couple also had two daughters who were living with their husbands. When we first meet him, Utsugi was also recovering from a stroke that paralyzed his hand. He then started writing his journal, pouring into its pages his innermost thoughts. The looming presence of death was prevalent. However, there was one subject that the journal fixated on: the old man’s growing erotic obsession with his daughter-in-law. Now, this subject is not something new in Tanizaki’s works so I did not find it particularly off-putting. Moreover, the premise did remind me of Yasunari Kawabata’s The House of Sleeping Beauties and Gabriel García Márquez’s Memories of My Melancholy Whores, particularly in how they captured aging and sexual desire. Diary of a Mad Old Man probes into this obsession, resulting into a compelling read.

One thing I wanted to address during my foray into Japanese literature is my limited exploration of the works of female Japanese literature. As such, I planned to read Banana Yoshimoto’s Asleep, on top of Yōko Tawada’s The Last Children of Tokyo which I read earlier in the month. I originally planned more but I guess I failed. Nevertheless, I looked forward to reading Asleep because it is going to be my second novel by Yoshimoto; the first, of course, was her popular debut novel Kitchen.

Yoshimoto established a reputation as a short story writer and this quality came across in both of her books I read. Asleep was advertised as a novel but it is actually a collection of short stories that were visibly connected by the overriding theme of sleep and some other similar elements, e.g. young women as main characters. The first story, Night & Night’s Travelers conveyed the story of 22-year-old Shibami who recently lost her brother Yoshihiro to a car accident. Her grief made her sleepwalk barefoot on the snow; the snow was another leitmotif. The second story, Love Song, was pretty similar to the first story. Fumi, the main character, was an alcoholic. Before she could sleep, she hears a song that reminded her of Haru, a woman she once fought with over a man. In the third story, Asleep, the readers meet Terako, a chronically tired woman. The novel’s slender frame belies the big punches it has in store. It is a compelling story about death, grief, change, and life in general.

Although it was without design, I closed my May Japanese Literature reading journey in the same way I opened it: reading a novel by the highly-heralded writer Haruki Murakami. Murakami just released his first novel in six years and also received Spain’s Princess of Asturias Award for Literature, the highest literary award in Spain. While waiting for his latest work to be translated into English, I decided to read Dance Dance Dance – this was deliberate – and South of the Border, West of the Sun – this was unplanned. In reading the latter, I am just one novel away from completing all his novels; yes, the last one was the most recent.

Anyway, South of the Border, West of the Sun chronicled the story of Hajime. He was the only child of a couple living in a small Japanese town. While attending school, he met Shimamoto, the newest transferee. She had polio and like Hajime, she was an only child. Inevitably, the two developed a deep friendship with hints of a budding romance. They drifted away during their high school years as Hajime moved towns. Memories of Shimamoto, however, would haunt him even when he got married and had two daughters. With help from his father-in-law – rich but with some hints of underground dealings – Hajime became the owner of two successful jazz bars. Who’d have thought that a simple magazine feature would lure in Shimamoto? They would rekindle their lost romance but at what cost? The novel was classic Murakami but it also showed other aspects of his writing, something that I have observed in his works with lesser elements of magical realism. It was a quick read but memorable nevertheless.

What will you read next?

From China, I am looking at traveling to South Korea; this is essentially a literary tour of East Asia. I was surprised when I learned that Han Kang released a new work, or at least one of her previous works written in Korean was translated into English; the book was originally published in 2011. As such, I did not hesitate to buy Greek Lessons when I came across a copy of the book. All three of Kang’s novels I read gave me different experiences. I think I can expect the same with Greek Lessons.

From East Asia, I plan to move to South Asia. Like Chinese literature, Indian literature is one part of the literary world I admit I have underexplored. However, I plan to redress this by reading at least three novels by Indian writers this year. One of them is Deepti Kapoor’s Age of Vice. The book is also part of my 2023 Books I Look Forward To List. I am basically hitting two birds with one stone. Up next, I will move further west with French-Iranian author Négar Djavadi’s Disoriental. Disoriental was originally written in French and, from what I understand, provides an evocative portrait of contemporary Iranian history and politics.

That’s it for this week’s WWW Wednesday. I hope you are all doing great. Happy reading and always stay safe! Happy Wednesday again!

💜

LikeLike