The Feeling of Disorientation

Stepping out of one’s comfort zone. This is a phrase that has become ubiquitous. One hears it almost at every turn, in every circumstance. Do you want to discover more about yourself? Step out of your comfort zone and push your boundaries. Do you want to get promoted in your job? Step out of your comfort zone and be more proactive. Do you want to explore what life has in store beyond the box you placed yourself in? Step out of your boundaries and seek adventure for life is just out there, waiting for you to make it happen. Don’t just wait for life to happen to you. You can make your life happen, just consume a dose of the old prescription: step out of your comfort zone.

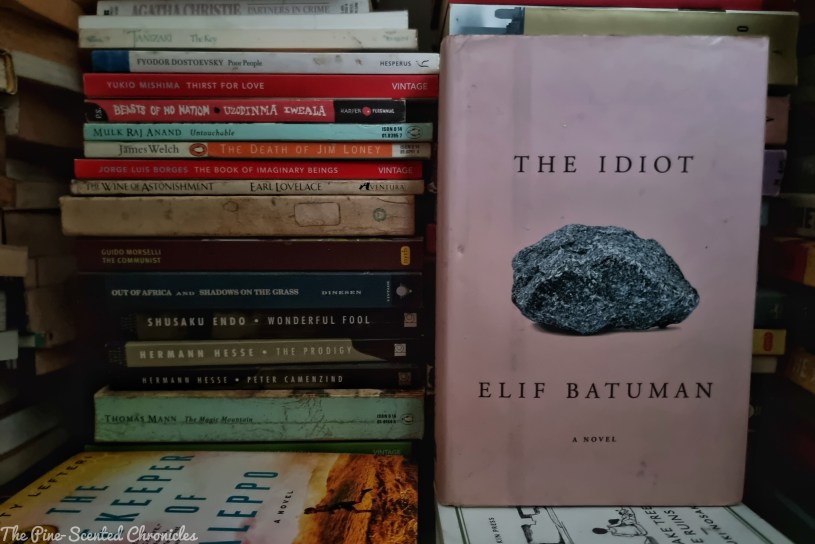

But stepping out of one’s comfort zone can be disorienting. It can be uncomfortable. Finding one’s self in the midst of an unfamiliar place populated with unfamiliar faces can be quite unsettling. It can be very daunting as several contrasting and, at times, unrelated factors come into play. But that is where stepping out of one’s comfort zone finds its value. By pushing our boundaries, we learn our limits. While the intent is, overall, great, such drastic action is not bereft of its own set of challenges. This was something that Selin Karadağ immediately learned when she entered the vaunted and storied halls of Harvard University in the fall of 1995. This chapter in her life was captured by Elif Batuman in her debut novel, The Idiot.

The eponymous idiot, Selin was a first-generation Turkish-American. She grew up in suburban New Jersey although her parents are no longer together. Her father currently lives in Florida with his new wife and Selin’s half-brother. Meanwhile, Selin’s mother was dating an American man while working as a researcher for a local university. Selin also has extended family residing in Turkey. Every summer, Selin and her mother traveled to Turkey to visit their relatives. When the readers first meet her, she arrived for orientation at Harvard as a freshman. In one of the most prestigious universities in the world, Selin was about to pursue a study in linguistics. In her new environment,

“Your message wasn’t easy to understand. I guess I’m too used to thinking of words as a means to an end. Words create a mood, but they aren’t the mood itself. I definitely agree that some moods can’t be conveyed by clear and logical language, or by essays. Essays can be such a pain! Basically, the reader isn’t on your side, so you can’t leave out any of the logical steps. And sometimes when a connection is delicate, the steps take too long to spell out – it just isn’t possible, by the time you get to the end of the steps, the mood is lost.”

~ Elif Batuman, The Idiot

Selin, however, is far from the “idiot” that the book’s title purported her to be. Moving out of her mother’s house for the first time, Selin was faced with challenges as she endeavors to steady the ship, her own ship. Taken out of her comfort zone, she struggled to find a sense of herself in a world far detached from the one she previously knew. Concern after concern started to pile up. Several questions started gnashing on her mind, from the profound to the more complex. Will she be able to adjust to her new environment? Will she be able to make new friends or at least establish connections with other people? What will she learn or uncover in this new environment and from this group of people?

With particular emphasis on the individuals that Selin met during her freshman year and the interactions she had with them, the novel charted Selin’s freshman year at Harvard. This eclectic cast of characters, interestingly, was comprised of several students who, like Selin, have mixed heritages. Harvard has become a melting pot where different adolescents converged in hopes of fulfilling their dreams. Her dorm roommates, for instance, were Hannah, a Korean-American; and Angela, an African American. Her two roommates also represented the two ends of the spectrum, with the former loud and the latter more conservative. In a Russian linguistic class she enrolled in, she met and befriended Svetlana, an international student from Serbia. Her other friend was Ralph, a good-looking student with an unusual obsession with the Kennedy family.

While she gained a couple of friends, Selin was socially behind her peers. She was averse to alcohol and even music, two things a majority of her agemates partake of in abundance. Partying was not her thing. Her social ineptitude easily set her apart. Getting along with other individuals, however, was not Selin’s only concern. The more she immersed herself in university life, the more she grew disconcerted. She had to deal with failures, such as not making it into the university orchestra. Missing the cut for the classes she wanted to attend, she was forced to take linguistics and philosophy of language classes that barely stimulated nor challenged her intellect. After Years of excelling academically, it can be unsettling to realize that you are not as brilliant as you think you are, that what everyone saw as remarkable intellectual capacity was just the norm.

Electronic mail, more popularly referred to in its protracted form as email, while it was in its infancy during the period, confused her at the onset. Batuman painted an evocative portrait of a young woman flailing in her new environment, akin to a fish out of the water. She soon found equilibrium with the entry of Ivan, one of Selin’s classmates in her Russian language class. Ivan was Hungarian and was a senior student studying mathematics. He was also good-looking and dreamed of further pursuing a post-graduate degree in mathematics at a graduate school in California. Their initial interactions, however, were not promising. Verbal communication did not immediately commence. They first became class partners acting out scenarios from a class text titled Nina in Siberia, a didactic story that doubled as a Russian grammar primer.

“I wanted to know how it was going to turn out, like flipping ahead in a book. I didn’t even know what kind of story it was, or what kind of role I was supposed to be playing. Which of us was taking it more seriously? Didn’t that have to be me, because I was younger, and also because I was the girl? One the other hand, I thought that there was a way in which I was lighter than he was – that there was a serious heaviness about him that was foreign to me, and that I rejected.”

~ Elif Batuman, The Idiot

It was, however, through another medium of exchange that their friendship blossomed. Emails, at the onset, confused Selin but she soon found value in sending and receiving emails when it bridged the gap between her and Ivan. At first, it was Ivan’s emails that reeled Selin in. His emails were far from casual. Ivan’s emails varied from affectionate to intellect. Some were torturous but they were generally poetic. Digital space subverted reality. For Selin, however, it was more than a correspondence as she slowly found herself falling for Ivan, although she was unsure most of the time of how she felt. “It was like the story of your relations with others, the story of the intersection of your life with other lives, was constantly being recorded and updated and you could check it at any time.”

The backbone of the story was the budding relationship between Selin and Ivan. It was not only his emails that made people gravitate toward Ivan. As one of Selin’s friends described him, Ivan is “a seven-foot-tall Hungarian guy who stares at everyone like he’s trying to see through their souls.” To grow closer to Ivan, Selin realigned her life and her personal priorities. For instance, during their summer break, she traveled to a remote Hungarian village to teach English. Selin did things she would not normally do, such as consuming large quantities of sour cream and even standing as a judge for a contest. While their communications can be emotionally intense, their relationship never went beyond platonic. It was against Selin’s case that Ivan was already in a relationship.

In a way, Nina in Siberia was a foreshadowing. Generally, one warms up to stories exploring baser human emotions, such as falling in love. Through the story of the seemingly star-crossed lovers, Batuman vividly captured the entanglement of desire and longing. But these two elements can also be achingly frustrating, as portrayed in the unfolding of the relationship between Selin and Ivan. It was palpable to everyone, from the readers to Selin’s friends, that their relationship will not blossom. Selin was also slow in the uptake. She cannot, rather refuse to recognize the telltale signs that were before her. Her vision was blurred by Ivan’s charms. There is a hopeless romantic in all of us.

All throughout the novel, the overriding themes – language and communication – were prevalent. The most direct reference was the characters themselves. Selin and Ivan, and all the other students that Selin befriended came from different cultures and languages. Selin enrolled in a Russian class and was majoring in linguistics. While studying, Selin taught ESL. Her internal monologues were preoccupied with what language can do as well as its limits. Ironically and perhaps deliberately, Selin had a challenge communicating with the people around her. She struggled with coming to terms with what she felt for Ivan. The primary reason for their romance not blossoming into something deeper was rooted in the fact that they cannot communicate their feelings well enough.

“I kept thinking about the uneven quality of time – the way it was almost always so empty, and then with no warning came a few days that felt so dense and alive and real that it seemed indisputable that that was what life was, that its real nature had finally been revealed. But then time passed and unthinkably grew dead again, and it turned out that that fullness had been an aberration and might never come back.”

~ Elif Batuman, The Idiot

Cultural touchstones further enriched the tapestry of the novel. Batuman, who was swept away by Russian literature at a young age, adapted the title of her first two books – The Possessed and The Idiot – from the works of her favorite writer, Fyodor Dostoyevsky. Batuman, however, did not limit her literary references to her favorite writer. The book’s epigraph, for instance, was from Marcel Proust. Selin, a bookish character, saw the world as a novel. This inevitably shaped how she perceived the world and interpreted the actions of the people around her. The novel was also riddled with details of Turkish culture. In Turkish, if one says that “her head hasn’t reached the chimney yet” it implies that a girl was still young enough for marriage.

Beyond the romance, what propelled the story was Selin. As a character, she was well conceived by Batuman; this can be attributed to the fact that the novel was semi-autobiographical. Regardless, Selin’s contrasting characteristics make her a complex yet relatable character. She was both naive and sarcastic. She conforms but she also challenged norms. She was also unsure of how to act most of the time. Her decision-making was spontaneous at best. But what made her a particularly endearing character was her ignorance and her awareness of it. She was cognizant of her own idiocy and her own shortcomings. A typical novel would have romanticized these facets of the heroine. And it was fine because it is a rarity to find a literary character that is beyond ideal. She used her own shortcomings as a springboard to be better.

The Idiot grappled with several questions – these questions were never treated as mere products of youthful enthusiasm – but the story was bereft of answers and solutions. It was all deliberate as Batuman coaxed the readers to explore their own selves to find the answer to these complex questions. It was effective in eliciting the sympathy of the reader as they become attuned to Selin and the manner in which her mind and, by extension, her heart worked. In this aspect, The Idiot is a compelling coming-of-age novel with dashes of philosophical intersections. In her debut novel, Batuman provided a lush tapestry where romance, language, and philosophy converged. The perfect mix of awkwardness and humor, coupled with the accessible writing, made The Idiot an insightful and interesting read.

“I wanted to know how it was going to turn out, like flipping ahead in a book. I didn’t even know what kind of story it was, or what kind of role I was supposed to be playing. Which of us was taking it more seriously? Didn’t that have to be me, because I was younger, and also because I was the girl? One the other hand, I thought that there was a way in which I was lighter than he was – that there was a serious heaviness about him that was foreign to me, and that I rejected.”

~ Elif Batuman, The Idiot

Ratings

75%

Characters (30%) – 24%

Plot (30%) – 20%

Writing (25%) – 21%

Overall Impact (15%) – 10%

When I first encountered Elif Batuman’s The Idiot about six years ago, I was reluctant to obtain a copy of the book. It was ubiquitous and there was hype surrounding it; I am usually averse to books that generate so much hype. But time and again, my curiosity got the better of me. Besides, the title reminded me of a book by Fyodor Dostoyevsky of the same title. The Russian writer was actually mentioned in the book with the primary characters discussing the merits of his oeuvre. Actually, the book is not part of any of my reading challenges but since I am also looking to expound my boundaries, I made the book part of my foray into American literature. I have mixed feelings about the book. The writing was accessible, hence, it was an easy read. However, it dragged at parts and Selin can be a frustrating character although her freshman experiences were something many of us can relate to. I am seriously considering reading its sequel, Either/Or.

Book Specs

Author: Elif Batuman

Publisher: Penguin Press

Publishing Date: 2017

Number of Pages: 423

Genre: Literary, Bildungsroman

Synopsis

The year is 1995, and email is new. Selin, the daughter of Turkish immigrants, arrives for her freshman year at Harvard. She signs up for classes in subjects she has never heard of, befriends her charismatic Serbian classmate, Svetlana, and almost by accident, begins corresponding with Ivan, an older mathematics student from Hungary. Selin may have barely spoken to Ivan, but with each email they exchange, the act of writing seems to take on new and increasingly mysterious meanings.

At the end of the school year, Ivan goes to Budapest for the summer, and Selin heads to the Hungarian countryside, to teach English in a program run by one of Ivan’s friends. On the way, she spends two weeks visiting Paris with Svetlana. Selin’s summer in Europe does not resonate with anything she has previously heard about the typical experiences of American college students, or indeed of any other kinds of people. For Selin, this is a journey further inside herself: a coming to grips with the ineffable and exhilarating confusion of first love, and with the growing consciousness that she is doomed to become a writer.

With superlative emotional and intellectual sensitivity, mordant wit, and pitch-perfect style, Batuman dramatizes the uncertainty of life on the cusp of adulthood. Her prose is a rare and inimitable combination of tenderness and wisdom; its logic as natural and inscrutable as that of memory itself. The Idiot is a heroic yet self-effacing reckoning with the terror and joy of becoming a person in a world that is as intoxicating as it is disquieting. Batuman’s fiction is unguarded against both life’s affront and its beauty – and has at its command the complete range of thinking and feeling that they entail.

About the Author

Elif Batuman was born in 1977 in New York City to Turkish parents. She was raised in suburban New Jersey. She studied at the Harvard College, completing her degree in 1999. She received her doctorate in comparative literature from Stanford University. She also studied the Uzbek language in Samarkand, Uzbekistan while attending graduate school.

Batuman’s interest in literature started at a young age. Nobel Laureate in Literature Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s The Gulag Archipelago was the major factor in her appreciation of Russian literature; she read the book while in high school. Post-university, Batuman worked as a journalist. Her literary works have also appeared in prominent publications such The New Yorker, Harper’s Magazine, and N+1. These works would comprise her first book, The Possessed: Adventures with Russian Books and the People Who Read Them, a memoir detailing her experiences at Stanford University.

In 2017, Batuman published her first novel, The Idiot. The novel was largely based on her experiences while studying at Harvard. The book was warmly received by both readers and critics. It was a finalist for the 2018 Pulitzer Prize for Fiction. Batuman’s favorite writer is Fyodor Dostoevsky, hence, the references in her first two books. In 2022, Batuman published her sophomore novel Either/Or, a sequel to The Idiot. Batuman also wrote essays which appeared in prominent publications. Batuman was writer-in-residence at Koç University in Istanbul, Turkey from 2010 to 2013. She also taught at Stanford and was the the recipient of a Rona Jaffe Foundation Writers’ Award.

She is currently is a staff writer for The New Yorker and is currently residing in New York City. Batuman identifies as queer.

Nice review.

LikeLike