The Rise of Korean Literature

Long been overshadowed by the literature of its East Asian neighbors Japan and China, there has been a remarkable increase in the interest in the works of Korean literature. If the International Booker Prize longlist is any indicator, Korean literature is gaining traction on the international stage. In 2016, Han Kang’s The Vegetarian ((채식주의자) was awarded the first revamped International Booker Prize. Two years later, Kang’s 2016 novel The White Book (흰) made it to the shortlist. This was followed by more works of Korean literature landing on the prestigious award’s longlist. Among these works are Hwang Sok-yong’s At Dusk (해질무렵) in 2019, Bora Chung’s Cursed Bunny (저주토끼) and Sang Young Park’s Love in the Big City (대도시의 사랑법) in 2022.

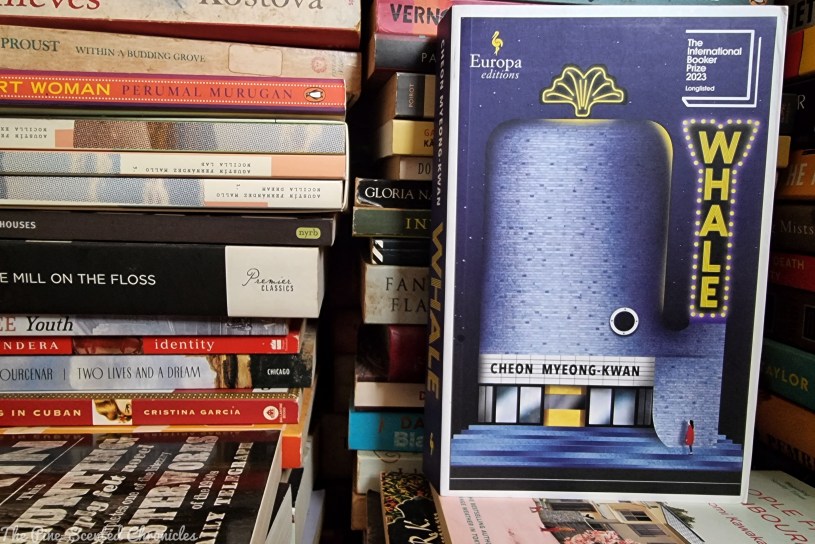

In 2023, another Korean writer, Cheon Myeong-Kwan (천명관), joined this growing impressive list of writers who are conquering the global stage. Also an established screenwriter and film director in his native South Korea, Cheon Myeong-Kwan’s debut novel, Whale was longlisted for the 2023 International Booker Prize. It would make it all the way to the shortlist but fell short of replicating Kang’s 2016 feat; the award went to Bulgarian author Georgi Gospodinov’s 2020 novel Time Shelter. While it may have not won the prize, Whale‘s longlisting for the literary award was more than enough to propel it to global recognition and make it an integral part of literary discourses.

Cheon’s promise as a writer was evident from the onset. His literary debut work, a short story titled Frank and I published in 2003, won the prestigious Munhakdongne New Writer Award. He rode this wave of momentum and a year later, he published his debut novel 고래 (Gorae). It was another feather in his cap as 고래 was both a commercial and critical success in South Korea. It won the 10th 문학동네소설상 (Munhakdongne Novel Award). In the ambit of modern Korean literature, the novel is considered a contemporary classic. Despite the book being a household title, it took nearly two decades before it was made available for anglophone readers. Translated by Chi-Young Kim, the novel was published as Whale, the literal translation of the novel’s Korean title.

“She wasn’t obsessed with the whale just because of its size. When she saw the blue whale from the beach, she had glimpsed what eternal life looked like, life that had triumphed against death. That was the moment the fearful small-town girl became enraptured by enormous things. She would try to use big things to beat out small things, overcome shabbiness through shiny things, and forget her suffocating hometown by jumping into the vast ocean. And finally, she became a man to hurdle over the limitations of being a woman.”

~ Cheon Myeong-Kwan, Whale

“Chunhui – or Girl of Spring – was the name of the female brickmaker later celebrated as the Red Brick Queen on being discovered by the architect of the grand theater. She was born one winter in a stable to a beggar-woman, as the war was winding down. She was already seven kilos when she emerged and plumped up to more than a hundred kilos by the time she turned fourteen. Unable to speak, she grew up isolated in her own world. She learned everything about brickmaking from Mun, her stepfather. When the inferno killed eight hundred souls, Chunhui was charged with arson, imprisoned and tortured. After many long years in prison, she returned to the brickyard. She was twenty-seven.” Without a preamble, this was how Cheon’s debut novel. It instantly set out the landscape of the novel. At the same time, it invites questions. Who is Chunhui? Why was she charged with arson? Who is Mun? Soon enough, Cheon started building the story from the ground up.

Chunhui was one of several women whose lives and stories intersected in Cheon’s complex and multilayered novel. From the story’s present, the novel transported the readers back to the past to fill in the gaps. The setting was post-war South Korea. The novel introduced the second of the three women at the heart of the narrative, the beggar-woman who was Chunhui’s mother, Geumbok. While the story was populated with several characters whose individual threads gave the story different complexions, it was Geumbok’s story that was the story’s backbone. Geumbok was born in a remote mountain village. Her father was a drunkard and it wasn’t long before she fled to a coastal city. She hitched a ride with an itinerant fishmonger, the first in a long line of men beguiled by Geumbok; she had that inexplicable but potent appeal that reels men in.

Stepping out of the mountain was an exhilarating experience for Geumbok. Her spirits soared higher when she saw the sea. There was one thing in particular thing that left a deep impression on her: the sight of a whale breaching out on the ocean. Even those who have witnessed such a sight are enchanted every single time. What more for the mountain-raised Geumbok? This vision sparked the flames inside Geumbok. The image of the vast ocean and the whale inspired her to dream big and be successful. Whales, the leviathans of the sea, after all, often represent something unattainable and mysterious in literature. “When she saw the blue whale from the beach, she had glimpsed what eternal life looked like, life that had triumphed against death.”

Slowly but surely, Geumbok started making good on this promise. She entered into relationships with men. They were initially the means for her to survive and eventually springboards to rise above the ranks. At the coastal city, she traded preserved cod and squid with the fishmonger who was also her lover. She ditched him for the owner of a cinema, a Yakuza repeatedly referred to by the novel’s omniscient narrator as “man with the scar, the renowned con artist, notorious smuggler, superb butcher, rake, pimp of all the prostitutes on the wharf, and hot-tempered broker”. A third lover led Geumbok out of the coastal city and back to the mountains, to a tiny and impoverished hamlet called Pyeongdae. It was the frontier, out-of-reach of development but it was in Pyeongdae that Geumbok reached higher levels of success.

“For the first time in a long while, she felt refreshed. Her senses felt sharper and she was alert to what was mixed into the wind — the damp darkness of the valley, the smell of racoons sleeping among the rocks below, the scent of various grasses growing in the fields. She was gradually relaxing from the years she’d spent on edge, and she was glad to have returned to where she belonged.”

~ Cheon Myeong-Kwan, Whale

Geumbok’s potent effect on men was a legend on its own but this only obscured her real capability. She possessed business acumen and a deep understanding of everything that entrepreneurship entailed. It was at this juncture that she reinvented herself. When an opportunity presented itself, she took it. From the dust of the countryside, she started a brickmaking company. At the onset, it seemed a pipedream. The countryside is barely accessible. How will the bricks sell? Geumbok, however, was not one to be easily disheartened. After all, the road to success is fraught with obstacles. Rather than wallowing in misery, she made her brain cells think of ways to get the word out; the bricks they made were of the highest quality. And then it finally came. A potential customer managed to find the out-of-way brickyard. Through word of mouth, it didn’t take long before Pyeongdae’s bricks started selling like hotcakes.

Along with the success of Geumbok’s brickyard came development and also changes; this is a recurring theme in history. As Geumbok’s business grew, so did the community around it. As development came knocking in, Pyeongdae started to grow exponentially: “Around this time, the wave of modernity swept forcefully into Pyeongdae, which began to expand rapidly. Electricity came to teach house, along with telephones.” The presence of the railroad further exacerbated this growth. Investments came rushing in. Money and trade came rushing it. Geumbok also contributed to the town’s commercial growth by opening a huge cinema shaped like a whale breaching out of the water.

Once a sleepy mountain village, Pyeongdae became a bustling population center. It grew in prominence that it elicited visits from prominent people from other parts of the country. In several aspects, the story of Pyeongdae mirrored South Korea’s contemporary history. In a way, Pyeongdae was a microcosm. Through the rise of Pyeongdae from relative obscurity, Cheon painted an evocative tapestry of South Korea’s growth following the end of the Korean War. As the dust of the war started to settle, what ensued was a period of unmitigated growth. South Korea was like a phoenix rising from the ashes as prosperity and modernity barged in. Once it was able to stand on its own again, South Korea soared to become one of the world’s most highly developed countries.

Along with the good came the bad. Geumbok’s aspiration for Pyeongdae was hounded by a curse invoked by an old crone and her daughter, a one-eyed woman who can control bees. This also holds true for the story of South Korea. The country’s golden age was undermined by dark realities. Whale reiterated a universal and ugly reality: the robust economy was built from the hard work and industry of ordinary people who were exploited by opportunists for the selfish purpose of generating fortunes. More often than not, worker safety was compromised to save cost. Their welfare is not considered as corporate greed seizes businessmen. But when the exploited attempt to voice their discontent, they are silenced by force.

“Purslane, thistle and foot-tall weeds had worked their way up through the hard, trampled earth and grown thick and tangled around the kilns. Daisy fleabane in particular had always crowded the perimeter of the brickyard like soldiers surrounding a forest, and once the humans were gone the plant had instantly infiltrated the site, occupying the entire place.”

~ Cheon Myeong-Kwan, Whale

Apart from functioning as a social commentary, the novel also doubled up as a political commentary. Cheon did not skirt around critical phases of South Korea’s modern history. It is in tackling this subject that the novel’s satirical elements soared. As each character’s backstory was crafted by Cheon, we read about the effects and consequences of corruption and nepotism. Cheon also did not shy away from underscoring political suppression, including the oppression of libertine ideals and the stifling of anti-communist sentiments. Communist ideology once permeated South Korean politics; the sketchy figure of the General looming in the story’s background was a representation of this section of South Korean history. The impact of these elements on the ordinary Korean’s life was vividly captured by Cheon.

Without a doubt, Whale is a remarkable and magical chronicle of South Korea’s modern history. Geumbok’s story, on its own, was an astounding achievement of storytelling. We read the story of a tenacious woman who rose above adversity to succeed. Not only did she have to overcome several challenges such as poverty but she also had to constantly prove her mettle in a highly patriarchal society. For instance, when the predominantly male workers of the brickyard started to protest, she kept her composure. The novel also explored mother and daughter dynamics while, at the same time, tackling subjects such as sexuality, vengeance, and the nuances of lust and love.

The novel confronted South Korea’s rigid social norms when it featured a homosexual relationship; for a highly modernized country, South Korea still frowns upon homosexuality. In the latter parts of the story, there was a palpable shift in the pronoun of one character, as it shifted from “she” to “he”. Lest we forget, the novel was published in the early 2000s. The story also highlighted the pains of change. Some are amenable to it while some challenge it; this was evident when concrete was slowly replacing brick as the primary construction material. In one passage, a character “never dreamed the world would become filled with buildings made of cement.” While the story had its moments of reprieve jotted with humor and wit, a dark pall hovered above the story. Death was prevalent and the characters died from a plethora of manners. Characters died from suicide, electrocution, murder, and drowning. Violence, tragedy, and domestic abuse were prevalent. The novel was witty as it was dark.

The novel’s layers of satire were interjected with more eccentric elements. Chunhui was mute but she can communicate with Jumbo, a circus elephant who inevitably became a part and parcel of the family. Repetition of phrases was ubiquitous, along with pleas for the readers to be patient just when the story was about to meander. Following a didactic passage, the omniscient narrator follows it up with the phrase “That was the law of …” These laws range from the profound such as love, rumors, employment, recklessness, and obesity, to the more complex such as dictatorship, ennui, and intellectuals. Cultural touchstones, particularly critical films, added an interesting texture to the story. All of these different elements converge to create a lush tapestry astutely woven together by Cheons’s dexterous hands.

A novel of modern South Korea, Whale is a very complex and multilayered novel that reels the readers in its different elements. All of these were held together by Cheon’s storytelling who held the promise of his successful literary debut. It is an atmospheric story that fused social and political commentary with magical realist elements. Whale also subtly underscored the very nature of storytelling. It is also the story of a strong woman who rose above adversity and the patriarchy. At one point, Geumbok said “I only have one principle I live by. Small, humble things are embarrassing.” This holds true for the novel: an ambitious undertaking that didn’t shy away from examining complex subjects and realities that some might find off-putting.

“By its very nature, a story contains adjustments and embellishments depending on the perspective of the person telling it, depending on the storyteller’s skills. Reader, you will believe what you want to believe. That’s all there is to it.“

~ Cheon Myeong-Kwan, Whale

Book Specs

Author: Cheon Myeong-Kwan

Translator (from Korean): Chi-Young Kim

Publisher: Europa Editions

Publishing Date: 2023 (2004)

Number of Pages: 367

Genre: Magical Realism, Historical

Synopsis

Whale is a sweeping, multi-generational tale that blends fable, farce and fantasy.

Set in a remote village in South Korea, Cheon Myeong-Kwan’s beautifully crafted novel follows the lives of three linked characters: Geumbok, an extremely ambitious woman who has never recovered from the indescribable thrill she experienced when she first saw a whale crest in the ocean; her mute daughter, Chunhui, who communicates with elephants; and a one-eyed woman who controls honeybees with a whistle.

Written by one of South Korea’s most original voices, Whale is a novel brimming with surprises and wicked humour; a picaresque narrative that casts a satirical eye on Korea’s whirlwind transformation into a highly developed and wealthy nation.

About the Author

Cheon Myeong-Kwan (천명관) was born in Yong-in, South Korea in 1964. Before embarking on a literary career Cheon first worked for a movie production company. He wrote the screenplays for films like Gun and Gun (1995, 총잡이) and The Great Chef (1999, 북경반점). While he wrote several other screenplays, the productions for these were either suspended or, worse, canceled.

It was at this critical juncture that Cheon started exploring writing as a means to earn a stable living. This transition in career began with the short story Frank and I which was published in 2003. It was critically received, earning Cheon that year’s Munhakdongne New Writer Award. A year later, he published his debut novel, 고래 (Gorae). 고래 was both a commercial and critical success in South Korea. It also won him the 10th 문학동네소설상 (Munhakdongne Novel Award). It was translated into English as Whale in 2023; there was an attempt at translation in 2016 by Dalkey Archive Press but it was never published. The second English translation earned Cheon a shortlist at the 2023 International Booker Prize.

Cheon’s second novel, 고령화 가족 (Goryeonghwa Gajok, Modern Family) was published in 2010 and translated into English in 2015. The novel was also adapted into a film, Boomerang Family, in 2013. His other works include the short story Cheerful Maid Marisa (2006) and the novel My Uncle, Bruce Lee (2013).

Reblogged this on Entirely consecrated beacon for secular existence’s contemplation.

LikeLike