Haunted by the Past

At the intersection of Asia and Europe lies the nation of Georgia. Tucked on the towering Caucasus Mountain, Georgia is one of the earliest known winemaking locations in the world; the region has been producing wine as early as 6,000 B.C. Due to its location, Georgia has been a part of different kingdoms and empires, such as the Kingdoms of Colchis and Iberia. During the medieval times, an influential and powerful kingdom emerged in the region, reaching its golden age between the 10th and 13th centuries. Due to internal strife, the once mighty Kingdom of Georgia declined. Its collapse was inevitable and soon, it was divided into three independent kingdoms. The fragmentation of the Kingdom made it vulnerable to the invasion of stronger regional powers that flanked the region.

For centuries, Georgia was alternately occupied by the Mongols, the Ottomans, and various dynasties of Persia. At one point, it was also a part of the Russian Empire. After the Russian Revolution of 1917, Georgia declared its independence on May 26, 1918, under the protection of Germany. However, it was short-lived as the victory of the Allies toward the end of 1918 led to the occupation of Georgia by the British. Following the end of the First World War, Georgia was invaded and annexed by the Soviet Union in 1922. For decades, Georgia was a Socialist Republic until Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev instigated reforms in the 1980s. Without wasting time, Georgia moved swiftly toward independence, and on April 9, 1991, Georgia officially became an independent nation.

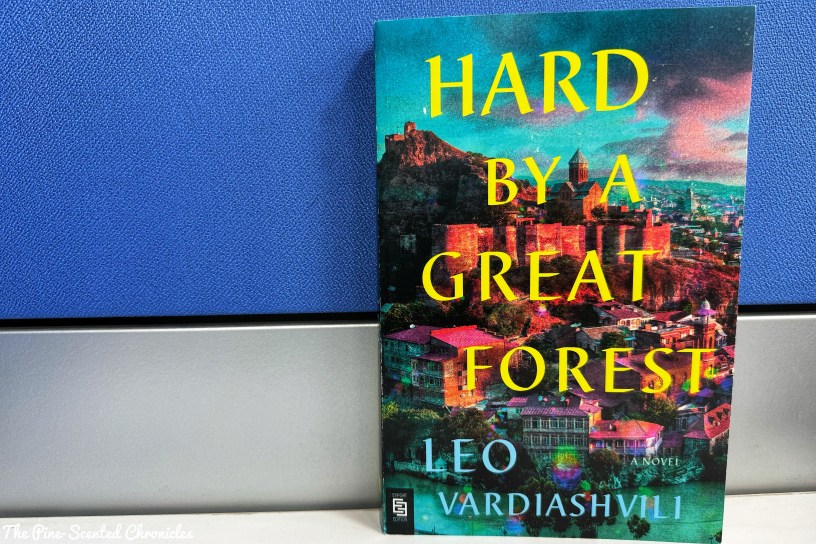

It is to this country with a colorful history that Leo Vardiashvili transports the readers in his debut novel, Hard by a Great Forest. At the heart of the novel was Saba Sulidze-Donauri. As a child, he, his older brother Sandro, and their father, Irakli, moved to London – Tottenham, specifically – from Tbilisi, Georgia in 1992. They were fleeing the spate of civil wars and instability that had gripped the newly independent nation shortly after it broke away from the Soviet Union. Seeking asylum in England, however, entailed leaving behind the family’s matriarch, Eka. A single parent in a foreign country, Irakli nevertheless worked hard for his sons. He also worked hard to save money so that he could pay for his wife’s bribe money for a visa and follow them to London.

“My job was to travel the country and give people bad news. In corporate, air‑conditioned meeting rooms, I told my audiences that some‑ day they would die. Yes, you in the back—you too. A Doomsday Peddler, according to Sandro. Like a good snake‑oil man, though, I had miracle cures to sell. I offered pensions and life insurance, investments and savings accounts. Useless acronyms, yield rates and percentages, sold to profit my em‑ployer. But also sold to stop these people from really absorbing my message and walking out of their jobs.“

~ Leo Vardiashvili, Hard by a Great Forest

All the while, Irakli kept promising his sons that Eka would soon be joining them. Earning a living, however, proved to be tough. It did not help that the cash meant to smuggle Eka out of Georgia was cheated out of Irakli. As the years passed by, the promise of Eka joining her family also started to fade. Irakli’s promises started to sound like a broken record. When news of her demise reached her family in London, they breathed a sigh of relief. Nearly two decades after they left their homeland, Irakli embarked on a return journey to Georgia. He was overwhelmed by homesickness. He was also driven by the desire to reckon with his past and his wife’s death. The passage of time has not blunted the desire to be back. “I’ll go back there, to all those places I didn’t say goodbye to,” Irakli would often tell his sons.

Everything was going well, at the start. Irakli was even able to communicate with his sons. Out of the blue, Irakli went incognito but after leaving his sons a cryptic message: “I left a trail I can’t erase. Do not follow it.” His sons, naturally, did not heed their father’s request; they were dutiful sons, after all. Without wasting another second, Sandro booked a ticket to Tbilisi and embarked on his own journey. However, it didn’t take long before Sandro also disappeared and lost communication with his younger brother. This left Saba to trace the trails left behind by his father and older brother. Now in his twenties and prone to panic attacks, Saba returned to his homeland. Donning his “lucky Pink Floyd T-shirt” was his first journey to the city of his childhood since fleeing his war-torn homeland.

When he arrived in Georgia, Tbilisi was just recovering from flooding that caused the animals from the city’s zoo to escape; Saba’s adventures and misadventures made him cross paths with some of these animals. Saba’s arrival also came with its own storm. Upon landing, he was immediately interrogated by the police about his last name. It was soon revealed that a warrant of arrest was out for his father for attempted murder. Saba’s passport was then seized. “The situation calls for someone with a plan. I didn’t even bring toothpaste,” Saba thought. He was thrown into a whirlpool where there was no looking back. As a reprieve, he summoned the ghosts of the dead to accompany him in his run-ins with the police.

Saba, now without roots in his homeland, found salvation in the company of Nodar, a taxi driver from the contested zone of South Ossetia, who greeted him at the airport. Recognizing the dangers of checking in to a hotel late at night, Nodar offered Saba his home, “hotel.” He also offered to accompany Saba in his quest. Nodar volunteered to be Saba’s guide who kept Saba abreast of the developments in the country since he fled from Georgia. In the quest for his father and brother, Saba was guided by a trail of clues to their father’s whereabouts left behind by Sandro. This came in the form of graffiti scrawled all throughout the city. On top of this, Irakli also left behind pages of a play. Irakli once told his sons: “I’ll leave the pages, here and there, like breadcrumbs. Right pages for the right place. My farewell. When I’m done, the breadcrumbs will bring me back here. Back to you.”

“They say an angel’s trapped in that tower. Not the winged, glowing kind that floats on a cloud, farting rainbows. No, this one’s the old Orthodox Christian kind. A terrible, vengeful angel. That tower can’t be taken by any enemy. Ottomams, Persians, Mongols, and all shades of Arabs tried. Only the Mongols ever got close. The angel sent down a thick fog. When it cleared, the Mongols were found torn limb from limb, scattered all around the watchtower, with only their livers eaten, as though by a wolf hunt.”

~ Leo Vardiashvili, Hard by a Great Forest

The graffiti Sandro painted all over the city took quotes from popular literary works such as Hansel and Gretel, Romeo and Juliet, and The Wizard of Oz; the book’s title was derived from the opening lines of Hansel and Gretel graffitied by Sandro in an alley. Even Charles Bukowski was quoted in the story. These are books and fairytales that their mother whispered to them. Whispered because the Soviet Union’s censorship banned them and the possession of which comes at a steep price. Hansel and Gretel was a prevalent presence. The “clues” left behind by both Sandro and Irakli were allegorical breadcrumbs that Saba needed to pick up to make it out of the allegorical forest.

Vardiashvili’s evocative and atmospheric writing made Tbilisi come alive. Through his vivid writing, the Georgian capital became a character in itself. Through the lenses of Saba – who himself was overwhelmed by nostalgia brought about by the feeling of being back in the city of childhood – Vardiashvili steers the readers across Tbilisi, making them walk the streets and drink in the sights of the city. Places such as Sololaki Hill, the City Zoo, Liberty Square, Vake Park – the district of the affluent – and even the Kukia Cemetery have become familiar sights. We also walked down and saw the pastel houses of Galkation Tabidze Street. Some of the memories attached to these places by Saba were bleak but through Vardiashvili’s writing, these places gave the city a distinct character.

As Nodar ferried Saba across the city and, eventually, the country, we witnessed a country still reeling from the wounds of history. Those who were left behind in Georgia during the post-Soviet collapse held grudges against those who fled. Meanwhile, remnants of the country’s Soviet connections were slowly being demolished to reestablish Georgia’s identity. The contours of Georgia were further captured when Saba and Nodar traveled to the hinterlands of the Caucasus. Saba was in awe of the sheer beauty of the mountains but was also astounded by the remnants of the wars that have altered the landscape of Georgia. On the way to the monastery town of Ushguli, Saba and Nodar met Dimitri who was also making his way to Ushguli. He came from the Republic of Abkhazia, a region that broke away from Georgia but is internationally recognized as a sovereign territory of Georgia.

The conflict between Georgians and Abkhazians was referenced in the story, and so was the more recent conflict in South Ossetia. Ossetians, like their Abkazians and with the backing of the Russians, wanted to separate from Georgia. Dimitri also had Ossetian blood while Nodar was originally from the region before he and Ketino, his wife, moved to Tbilisi to flee from the war. When Nodar and Saba’s quest took them to Ossetia, Nodar was hopeful; his daughter fled to Ossetia but he was unable to go and find her because crossing the border, even for Ossetian civilians, is akin to crossing the Rubicon. The borders are heavily guarded and those who cross the borders are suspected as separatist traitors who favor Russian occupation. It was literally Georgians going against their fellow Georgians. In Nodar’s words: “Russians, Georgians. What’s the difference? Shell’s a shell – it still kills.”

“Only the willingly ignorant can sit around and summarize such terrible things into pert little sentences about some god. Gods only exists because sometimes reason is too stark and too true. There is no golden silk thread of meaning that brought me here. Meaning and reason are not the same thing. Sometimes there’s no meaning to why things happen. But reason cuts the bullshit like a knife.”

~ Leo Vardiashvili, Hard by a Great Forest

All of the novel’s elements were woven together by Vardiashvili’s writing into a lush tapestry. His writing is most affectionate at points where Saba reckons with the past. Saba was obsessed not only with finding his father and brother but also with the past, hence, the ghosts that surrounded him during his journey. Betrayals and guilts float to the surface but holding grudges can be overwhelming, as was the case with Irakli. Someone has to break this cycle and Saba, with the ghost of his grandmother Lena’s urging, was bound to “break the cycle.” Nodar provided comic relief and was almost the life of the story. He was also the personification of the Georgian spirit. Nodar, with his wit and unfiltered opinions, was Saba’s window to a world he had long forgotten. He even gave Saba the moniker Mowgli, from Rudyard Kipling’s The Jungle Book.

Hard by a Great Forest is, at its heart, a novel about Georgia. Its history, people, and culture were examined through the story of a family who was haunted by memories of the recent past. It is these memories that drove them back to where they started. Through Saba’s adventures and misadventures, Vardiashvili painted an evocative portrait of a country reeling from the consequences of war that has threatened it for decades. Saba’s quest for his father and brother across Georgia is a documentary of how wars, sometimes Georgians against Georgians, have indelibly altered the nation’s landscape. Beyond wars and families, the novel is about loss, the refugee experience, and the stories illuminating our path. It is a story of the survivors and also of those who were not able to survive. While it was brimming with references to fairy tales, Hard by a Great Forest is far from a fairy tale. Nevertheless, it beacons with a hopeful message.

“When the Turks came, or whoever’s turn it was to fuck us, people ran away and hid in the mountains. They left everything behind, but they took grapevine cuttings from their vineyards. They kept those alive at all costs so they’d have someplace to start if they ever returned home. Sometimes, brother, cuttings passed between generations. Kept alive in the mountains for decades. Wine isn’t in our blood. It is our blood.“

~ Leo Vardiashvili, Hard by a Great Forest

Book Specs

Author: Leo Vardiashvili

Publisher: Riverhead Books

Publishing Date: 2024

Number of Pages: 338

Genre: Literary, Historical

Synopsis

Saba is just a child when he flees the fighting in the former Soviet Republic of Georgia with his older brother, Sandro, and father, Irakli, for asylum in England. Two decades later, all three men are struggling to make peace with the past, haunted by the plates and people they left behind.

When Irakli decides to return to Georgia, pulled back by memories of a lost wife and a decaying but still beautiful homeland, Saba and Sandro wait eagerly for news. But within weeks of his arrival, Irakli disappears, and the final message they receive from him causes a mystery to unfold before them: “I left a trail I can’t erase. Do not follow it.”

In a journey that will lead him to the very heart of a conflict that has marred generations and fractured his own family, Saba must retrace his father’s footsteps to discover what remains of their homeland and its people. Savage and tender, compassionate and harrowing, Hard by a Great Forest is a powerful and ultimately hopeful novel about the individual and collective trauma of war, and the indomitable spirit of a people determined not only to survive, but to remember those who did not.

About the Author

Leo Vardiashvili was born on September 14 in Tbilisi, Georgia where he was also raised. When he was twelve, his family moved to London as refugees, fleeing from Georgia’s post-Soviet regime. Vardiashvili studied English literature at Queen Mary University of London. He made his literary debut in 2024, with the publication of Hard by a Great Forest.