Happy Thursday! I just came across The Alphabet of Authors Challenge through One Book More. I didn’t sign up for the 2023 challenge but I am still interested to see how I fared. Basically, for The Alphabet of Authors Challenge, you have to read a book by an author whose last name begins with each letter of the alphabet. It also has a book title equivalent, The Alphabet Book Titles Challenge. For this post, however, I will only be checking on how I fared with the former. Here goes!

A: Jabari Asim

Jabari Asim was a writer I was unfamiliar with. Had it not been a fellow book reader, I might not have even considered obtaining a copy of his latest book, Yonder. I have been meaning to get around the book during the previous year but other books got in the way and Yonder was left to gather dust on my bookshelf. This 2022 reading catch-up has allowed me to finally delve into this book. Asim, I have learned, has been a prolific writer and Yonder was his third novel; he also wrote short stories, poetry, and children’s stories. When I started reading Yonder, I had no expectations of it. Once I opened the first pages of the book, I was slowly reeled in by the compelling voices that haunted the pages of the book. The novel transported me to the slavery era Deep South. The setting was a plantation, Placid Hall, owned by Randolph “Cannonball” Greene who also owned two other plantations, Pleasant Grove and Two Forks. However, the novel’s main voices were William, Margaret, Cato, and Pandora. Each character gave his or her account of how they were taken forcefully from their homeland by Thieves and sold to Greene; the group would refer to themselves as the “Stolens”. The story reminded me of Robert Jones Jr.’s The Prophets. I did like Yonder better, however. A review of the book I read also highlighted the parallels between this book and Ta-Nehisi Coates’s The Water Dancer. While I haven’t read Coates’s debut novel, Yonder was the image of it I had in my mind.

B: Julian Barnes

I wasn’t really planning to read Julian Barnes’ The Sense of an Ending last March. In the future, yes, but not right now. Had I not forgotten to bring Brighton Rock when I went to work, I wouldn’t have even started with the book although I was contemplating on which of the two books I should read after I read Virginia Woolf’s Orlando. But I guess I had no choice because, at some point in the future, I will be reading the book anyway. The Sense of an Ending is the third Booker Prize-winning book I read this year; after Shehan Karunatilaka’s The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida and J.G. Farrell’s The Siege of Krishnapur. At the heart of the 2011 Booker Prize-winning book was Tony Webster, who was already in middle age and was already divorced when we first met him. An unexpected bequest from a person whom he met only once in his life. This led to him flashing back into his past as he confronted events that have, in hindsight, impacted his life as an adult. The primary focus of his trip down memory lane was his childhood friends, whom he didn’t give much thought to previously. The book, somehow, reminded me of Herman Hesse’s Demian for some reason. The book’s thin appearance belies the deep and thought-provoking messages it carries within. Somehow, I wanted the story to extend a little more.

C: Cheon Myeong-Kwan

My journey across Asian literature took me to South Korea, with Cheon Myeong-Kwan’s Whale. Whale is the third work by a Korean writer I read this year. I first came across Cheon and his novel when Whale was announced as part of the 2023 International Booker Prize longlist. There has been a spate of Korean novels taking the world by storm; I am not complaining though. Whale, originally published in 2003, was Cheon’s debut novel and is considered a contemporary classic of Korean literature. The novel mainly charted the story of Geumbok. Born in a mountain village, she moved to a coastal city to escape from her abusive father. The sea mesmerized her but the sight of a whale breaching out on the ocean aroused the desire to break through in life. The story then charted her unusual effect on men and her various lovers, from a fishmonger to a Yakuza to a laborer. Her love affair with the laborer brought her back to the mountains, to the village of Pyeongdae where Geumbok established a successful brickmaking business. In a way, Pyeongdae was a microcosm of modern South Korea. Pyeongdae’s exponential growth and development were parallel to South Korea’s. The novel has several layers that make it a riveting read.

D: Négar Djavadi

My Asian literature journey took me to Iran with Négar Djavadi’s Disoriental which was originally published in French in 2016 as Désorientale. Djavadi and her family moved to France following the Iranian Revolution of the 1980s. Djavadi’s debut novel was a literary sensation in France, earning Djavadi several accolades. The story was narrated by Kimiâ Sadr and came in the form of a flashback. Kimiâ first painted an evocative picture of her family’s provenance, starting with her paternal grandmother Nour who was born in Iran’s northern Mazandaran province. Her father, Darius was the fourth of six brothers. Darius married Sara and the couple had three daughters. Weighing heavy on Kimiâ’s parent’s shoulders was the burden of society wanting a male child. The novel is a family saga but it is also an evocative painting of Iran’s contemporary history. Kimiâ’s parents were political activists, thus, setting them apart. With pandemonium inevitable during the Iranian revolution of the 1980s, Darius fled to Paris, with his wife and daughters eventually smuggled out of Iran. The other layers of Disoriental included Kimiâ’s recognition of her sexuality. Disoriental is a riveting read, recommended for readers who barely have an iota about Iran and its recent history.

E: Jennifer Egan

To be honest, I was ambivalent about exploring Jennifer Egan’s oeuvre. Sure, her Pulitzer Prize-winning novel A Visit from the Goon Squad was listed as one of 1,001 Books You Must Read Before You Die but learning about the discourse on its classification concerned me. I changed my mind when I learned about the release of Egan’s latest novel, The Candy House in 2022. I learned that it was a sequel to the aforementioned Goon Squad. I then gave both books a chance; I would end up liking Goon Squad, something I did not expect. A couple of months later, I would read The Candy House. As can be expected from a sequel, The Candy House involved several characters who were present in its predecessor. At its heart, the latest book provided an update on the main characters in the Goon Squad. Some of them have also grown up and pursued careers of their own. Some lost their charm while some gained renewed confidence. Both books would also share several attributes, such as their digression from traditional literary structures. Time was a relative concept as the story weaved in and out of the future and the past. The Candy House‘s structure, however, was not as pervasive as the Goon Squad. Memory was a seminal subject in the story and so was the exploration of the impact of technology on our lives, particularly how living online, i.e. social media, has adversely impacted us. As always, Egan does not fail to reel the readers in with her innovative writing.

F: James Gordon Farrell

It was through must-read lists that I first came across James Gordon Farrell. This then led me to his novel The Siege of Krishnapur which I, later on, learned won the Booker Prize and was even shortlisted for The Best of Booker (won by Salman Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children). I intended to read the book earlier but I held back when I learned it was part of the Empire Trilogy. The trilogy, I learned, grappled with the legacy of British colonialism. Sure enough, British colonialism was the heart of The Siege of Krishnapur, the second book in the trilogy; the three books can be read independently. The book transported me to the mid-19th century Indian subcontinent. At the heart of the story was the Indian Mutiny which included sieges into the cities of Cawnapore (Kanpur) and Lucknow. The events covered by the book were true but the novel’s setting, Krishnapur, was fictional. Krishnapur was the home of many a British colonist and was run by a man mainly referred to as the Collector; his name was Mr. Hopkins. It was the Collector who first recognized the trouble brewing over the horizon. He tried to raise the alarm but his pleas to Calcutta went unheeded and sure enough, a massacre of British forces in the nearby city of Captainganj spurred revolts across the region. The remaining British forces retreated to Krishnapur, hence, the book’s title. It was, overall, a compelling read that sheds light on a seminal part of India’s recent history.

G: Georgi Gospodinov

My European literary journey next me to Bulgaria, a part of the world of literature I have not ventured into ever. Enter Georgi Gospodinov who I learned about because of the International Booker Prize. I wasn’t originally too keen on his third novel Time Shelter but when it was announced as the winner, I needed to read the book. I wanted to know what the fuzz was about. Gospodinov, I learned, is quite a literary star in his native Bulgaria. When I was able to obtain a copy of the book, I resolved to make it part of my foray into European literature. The novel was narrated by an anonymous character but one can surmise him to be the author himself. A chance encounter with a mysterious man named Gaustine in Vienna led to a deep acquaintance which grew deeper into friendship after Gaustine set up a clinic in Zurich for the elderly who are suffering from Alzheimer’s disease. It was no ordinary clinic as it was comprised of different floors representing different decades and years of 20th-century Europe. The tailor-fitted rooms provided a sanctuary for people who wanted to find comfort in the past. It was a success but it soon became complicated when healthy individuals started flocking to his clinic to escape from the tediousness of the present. Time Shelter is no ordinary novel. It does not conform to the structural conventions of the typical novel and is parts-satirical and parts-philosophical. It also begs big questions related to memory and the past. Do the answers to the chaos of our quotidian lives lie in the past?

H: Amado V. Hernandez

Philippine literature – my own – is a largely unexplored territory. When the opportunity to read a third book by a Filipino writer presented itself, I did not hesitate. Amado V. Hernandez’s The Preying Birds was originally published in serial form before it was collectively published as a single volume in December 1968, carrying the title Mga Ibong Mandaragit. It was translated into English in 2022 as part of Penguin’s Southeast Asian Classics series. Set in the Philippines during the twilight years and the years immediately following the end of the Second World War, The Preying Birds is a scathing socio-political novel that strongly echoed the sentiments captured in the works of the Philippine national hero, Dr. Jose Rizal. The book’s hero, Mando Plaridel was reminiscent of Rizal’s Crisostomo Ibarra/Simoun. He used to be a servant in the household of wealthy landlord Segundo Montero. An act of betrayal turned him into a guerilla. By a stroke of luck, Mando succeeded in retrieving the chest of jewels that was thrown into the sea by Simoun. He then used the treasure to seek social justice. Social justice, however, is a rarity in a society corrupted by greed and personal ambitions. The maladies captured by Hernandez are concerns that remain prevalent in the present. The Preying Birds is, without a doubt, an incisive look at contemporary Philippine society.

I: Kazuo Ishiguro

While the 2017 Nobel Prize in Literature awardee Kazuo Ishiguro is listed as British, he is ethnically Japanese. He was born in Nagasaki before his father’s profession moved them to Guildford, Surrey when he was younger. Like Kawabata, Ishiguro was one of the first Japanese writers who sustained my interest in Japanese literature. With When We Were Orphans, I have now completed reading all of his eight novels. Like Japanese literature, Ishiguro’s oeuvre is diverse. With When We Were Orphans, he was again pushing the boundaries of his storytelling. Considered a work of detective fiction, the novel chronicled the story of Christopher Banks, a detective in 1930s England. The concern of the story, however, was his past which has always haunted him. Before moving to England, he lived as a young child in the Shanghai International Settlement until his father, an opium trader, and his mother, a staunch advocate against the opium trade, disappeared one after the other. The mystery never got solved until Banks decided to crack it. The novel also grapples with history, the opium trade, and corruption. The conclusion, however, was anticlimactic. The revelation toward the end was unexpected but not cathartic either.

K: Yasunari Kawabata

Japan produced three Nobel Laureates in Literature. The first of them was Yasunari Kawabata whose The Old Capital was among the three books the Swedish Academy cited for their selection of Kawabata. I can’t find what the other two books were but I assume it was Thousand Cranes and Snow Country. I could be wrong though. The Old Capital was my sixth by Kawabata, one of the first Japanese writers who was key in my growing interest in Japanese literature in general. The titular Old Capital was Kyoto, the setting of the story, and the old capital of Imperial Japan. Before the capital was transferred to Tokyo, Kyoto held the distinction of being Imperial Japan’s capital for nearly a millennium. The story, however, does not dive into history but rather, it captures the story of some of the members of the community. The novel’s main character was Chieko Sada, the daughter of Takichiro and Shige, the owners of a wholesale dry goods shop in Kyoto’s Nakagyo Ward. She found out she was a foundling but this did little to change her attitude toward her adoptive parents. Her life unraveled after a chance encounter at Yasaka Shrine made Chieko learn about Naeko, her twin sister. Personally, what made the novel flourish were the details of Kyoto that came alive. Festivals, temples, and streets came alive with Kawabata’s writing. It also helped that I have recently been to Kyoto. Overall, a good book very typical of Kawabata’s oeuvre.

L: Yiyun Li

I have read several positive feedback on the works of Yiyun Li, a Chinese-born writer who moved to the United States in 1996. I again crossed paths with Li in 2022 when her latest novel, The Book of Goose was released. The book was lauded by both literary pundits and readers alike. Curious about what the book has in store, I included it in my foray into Asian literature. Set in the French countryside shortly after the conclusion of the Second World War, the novel tells the story of a pair of thirteen-year-olds, Agnès and Fabienne. They were close friends. One day, Fabienne hatched a plan to write a story. She will narrate it while Agnès will write it. Helping them edit the book – a collection of morbid stories about dead babies – and finding a publisher was a local postmaster. The book, however, only had Agnès as author. Fabienne refused to have her name attached to the book. The book was a sensation and Agnès became the darling of the literary crowd; she was a prodigy. Despite this, the novel’s preoccupation was the friendship of Agnès and Fabienne which was both affectionate and strange. There is a fairy tale quality to the coming-of-age story.

M: Haruki Murakami

Although it was without design, I closed my May Japanese Literature reading journey in the same way I opened it: reading a novel by Haruki Murakami. While waiting for his latest work to be translated into English, I decided to read Dance Dance Dance – this was deliberate – and South of the Border, West of the Sun – this was unplanned. In reading the latter, I am just one novel away from completing all his novels; the only feather missing from my cap is his most recent. Anyway, South of the Border, West of the Sun chronicled the story of Hajime, an only child living in a small Japanese town. While attending school, he met Shimamoto, who, like Hajime, was an only child. She also had polio. Inevitably, the two developed a deep friendship with hints of a budding romance but they drifted away after Hajime moved towns. Memories of Shimamoto, however, lingered even when he got married and had two daughters. With help from his father-in-law – rich but with shady dealings – Hajime became the owner of two successful jazz bars. This lured in Shimamoto. They would rekindle their lost romance but at what cost? The novel was classic Murakami but with less surrealism. It was a quick read but memorable nevertheless.

N: Sōsuke Natsukawa

My foray into Japanese literature started rather slow – thanks to the thick The House of Nire – but it didn’t take long for me to gather momentum. This can be attributed to how much I have been enjoying Japanese literature, with its diverse and eccentric mix. Speaking of eccentricity, one of the eccentricities I have noted about this part of the literary world is the prevalence of cats. Several books involving cats were published or translated into English recently, among them Sôsuke Natsukawa’s 2017 novel 本を守ろうとする猫の話 (Hon o mamorō to suru neko no hanashi) which was translated into English as The Cat Who Saved Books. The premise was heartwarming but it didn’t seem that way at the onset because the readers were greeted with the sudden death of Rintaro Natsuki’s grandfather. This left the management of Natsuki bookstore in the hands of Rintaro, a subpar high school student who had the proclivity to distance himself socially from his peers; he was a hikikomori. Books were his comfort zone but he had to close his grandfather’s bookstore and move in with an aunt he didn’t know existed. His reverie was disrupted by the sudden appearance of a talking cat named Tiger the Tabby. Tiger the Tabby had a mission to save imprisoned books. This seemingly lighthearted story was an indictment of the current state of the publishing industry, academia, and the encroachment of capitalism on the simple pleasures of reading. It was a quick but compelling read that also doubled as a coming-of-age story.

O: Kenzaburō Ōe

Kenzaburō Ōe’s Death by Water. Death by Water was my fifth novel by Ōe although it was the first one I acquired. What held me back from reading the book was my apprehension to explore Ōe’s oeuvre. My curiosity got the better of me and in little under three years, I have completed five of his books. Like the two books by Ōe I read before it, Death By Water qualified as an I novel. At the heart of the story was Kogito Choko, or Kogii for short; he was the alter ego of the writer. The driving force of the novel is Kogii’s pursuit to complete a novel he started decades ago about his father’s death. However, his mother kept him from finishing it. Ten years after the death of his mother, Kogii, at seventy, was finally granted permission to open a stack of letters owned by his father, purporting to contain the secrets to his father’s life. The novel zeroed in on Ōe and discourses on his works form an integral part of the story. Some readers find authors inserting themselves in their works narcissistic, and to some extent, it applies in this case. However, it can also be attributed to the rumblings of an aging man who wanted to reconcile his memories, his dreams, and his realities. The novel underscored some seminal and timely subjects but it meandered.

P: Orhan Pamuk

I started my venture into Asian literature with the work of a Nobel Laureate in Literature. It is, thus, fitting that I end it with another Nobel Laureate in Literature. When I heard about Orhan Pamuk releasing new work in 2022 – at least a translation of his latest novel – I was among those eagerly waiting in anticipation. I was eventually able to obtain a copy of Pamuk’s latest novel, Nights of Plague, my fourth novel by Pamuk. The fact that the novel was about the plague was one of the reasons why I wanted to read it. Pamuk’s latest novel transports the readers to the turn of the 20th century, to the fictional island of Mingheria, one of the provinces that comprised the declining Ottoman Empire. It was on this remote island that Princess Pakize, “third daughter of the thirty-third Ottoman sultan Murad V” and her husband, Doctor Nuri Bey, were sent by Emperor Abdul Hamid to help aid in the quarantine efforts. A possible plague threatened the island. The novel explores how a plague can undermine the institutions meant to look after the welfare of a nation’s denizens. The novel eerily captured the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic. But it was also a novel about a declining empire, the intricacies of politics, the quest for independence, and the rise against colonialism and imperialism, with a murder mystery to boot. It was, as always, an interesting and insightful story.

Q: None

R: Rainer Maria Rilke

When a door closes, a new one opens. Immediately following the conclusion of my foray into Latin American literature, I commenced a literary journey across Europe. I opened my foray into European literature with a new-to-me writer but a writer who is quite ubiquitous. Austrian writer Rainer Maria Rilke has long piqued my interest; he is often part of literary discourses. However, his oeuvre is comprised primarily of poetry, an alley I still couldn’t imagine myself exploring, at least for now. I was surprised when I learned that he published a novel, The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge which I included in my 2023 Top 23 Reading List; this says how much I was looking forward to the book. As the title suggests, the book has an epistolary structure, interspersed with notebook and journal entries made by the titular Malte Laurids Brigge. In his mid-twenties, Brigge traveled from Denmark to Paris to document the works of sculptor Rodin. Through his notebook entries, Brigge captured life on the streets of Paris, beyond the glitz and glamour often attached to it. The novel transforms into a philosophical musing that revolves mainly around existentialism, detailed with childhood stories. Writing for Brigge was a distraction from his fear of death. The novel provides an intimate glimpse into the psychological profile of Rilke; some of the letters were actual letters Rilke sent his wife. Rilke’s poetic roots were palpable in the novel and some of his ramblings readers can relate to.

S: Natsume Sōseki

Of the many works of Japanese literature I wanted to read, one book has held my interest for the longest time: Natsume Sōseki’s I Am a Cat. The first time I encountered the novel, it immediately grabbed my attention. There was something about the book. However, I held back on purchasing the book because I was hoping to find a hardbound copy. Alas, the opportunity never presented itself. I can no longer keep the tenterhook. I am finally reading the precursor of all the cat-related works that proliferated Japanese literature. Interestingly, Sōseki had no plans of going beyond the first short story he wrote for the literary journal Hototogisu. Its popularity prompted the journal’s editor to convince Sōseki to write more. Ten more installments were thus written before it was published as a single book. It has since become a literary classic that transcends time. At the heart of the novel is a stray (unnamed) cat adopted by a middle-class family. The patriarch, Mr. Sneaze, was an English teacher. The story focuses on Mr. Sneaze’s interaction with his friends who frequent his home. Among them were Waverhouse and Avalon Coldmoon, a young scholar and Mr. Sneaze’s former student. through this eclectic set of characters, Sōseki probed into the social maladies of the Meiji era while also insights into the intellectual life during that period. A story that transcends time, I Am A Cat was a testament to one of the most revered names in modern Japanese literature.

T: Colm Tóibín

From outer space, my next read took me to a more familiar place: New York City, in particular, Brooklyn, one of the five boroughs that comprise the Big Apple. The spirit of Brooklyn was captured in Irish writer Colm Tóibín’s Brooklyn. I kept encountering the popular and highly-heralded writer and his works in must-read challenges; yes, these challenges and lists have given me names I have never heard of or whose work I have never read before. A couple of years since my first encounter with the Irish writer, I have finally read one of his novels. Set in the 1950s, Brooklyn chronicled the story of Eilis Lacey, a young Irish woman. After not being able to find work in Ireland, she immigrated to the United States with the assistance of Father Flood, a Catholic priest living in New York City. Eilis was able to find employment in a department store while taking night classes in bookkeeping, again, with the assistance of Father Flood and his donors; Eilis has a knack for bookkeeping which was not left unnoticed. As a licensed accountant myself, I did find this portion fascinating. Aside from this, the novel had elements of romance. However, the book’s strength lies in how Tóibín captured the spirit of Brooklyn in the 1950s. It was a melting pot of different cultures as it was where several immigrants such as Irish and Italians settled. Brooklyn made me want to read more of Tóibín’s works.

U: Ludmila Ulitskaya

I can’t remember when I first encountered Ludmila Ulitskaya. One thing is for sure, the Russian writer – at least her works – has been ubiquitous lately. This didn’t escape my attention. My interest in her oeuvre was further piqued when I kept seeing her name in discourses apropos possible honorees for the Nobel Prize in Literature. These were among the reasons why I listed her novel, Jacob’s Ladder, in my 2023 Top 23 Reading List. Said to be Ulitsakaya’s final full-length prose, Jacob’s Ladder follows two narrative threads: one in the present and one in the past. The present charted the story of Nora Ossetsky, a set designer, theatrical director, and writer in late-Soviet and post-Soviet Moscow. Following the decline of her marriage of convenience with Vitya, she raised her wayward son Yurik as a single mother. The second plotline followed the story of Nora’s grandparents Marusya Kerns and Jacob Ossetsky in the revolutionary and Stalinist periods. The second plotline was built from a cache of letters and journal entries made by Jacob uncovered by Nora while cleaning her grandmother’s house. On the surface, Jacob’s Ladder is a family saga oscillating across periods. Beyond the examination of family dynamics and strenuous relationships, the novel chronicled Russia’s modern history, from the fall of the Romanovs to the rise of Joseph Stalin to the dismantling of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. With the vast territory it covered, Jacob’s Ladder is certainly one of my best reads this year.

V: Mario Vargas Llosa

In lieu of Death in the Andes, I decided to read the 2010 Nobel Prize in Literature honoree Mario Vargas Llosa’s Aunt Julia and the Scriptwriter. Originally published in Spanish in 1977 with the title La tía Julia y el escribidor, Aunt Julia and the Scriptwriter was the Peruvian writer’s seventh novel and his third novel I read. Interestingly, this is the first that was set in his native Peru. The titular Aunt Julia was the love interest of Mario Vaguitas, an eighteen-year-old student who was also the novel’s primary narrator. The two were not related by blood but Aunt Julia, who was already thirty-two years old, was the sister of Mario’s biological uncle Lucho’s wife. She moved to Lima from Bolivia following a divorce. When they first met, Mario ignored her but the more he visited his uncle’s house, the more he became fascinated with Aunt Julia. It wasn’t long before it turned into a secret love affair; Mario’s family was against the affair. This was just one half of the story. The second thread charted Mario’s friendship with Pedro Camacho, the titular scriptwriter. Mario himself was an aspiring writer but he was slowly losing his passion. In contrast, Pedro had a prolific career as a writer for radio, with the plot of some of his serials woven into the story. The novel was based on Vargas Llosa’s first marriage. I did feel like the two strands did not converge but the novel was still a compelling read; one can expect nothing less from Vargas Llosa.

W: Virginia Woolf

In the ambit of literature, Virginia Woolf is a name that one will hardly miss, whether one is a devout reader or not. After all, Who is afraid of Virginia Woolf? I think it was through this movie title that I first came across the English writer although I wasn’t really into reading back then. The title, however, left a deep impression on me. I would, later on, learn that Woolf was a writer and I would explore her oeuvre years after my first encounter with her, starting with Mrs. Dalloway, a book I read way back in late 2018. The time is ripe to reconnect with one of the world’s most renowned writers and literary critics; she wasn’t a fan of James Joyce’s Ulysses. To be honest, I was surprised when I opened the book. The book’s introduction by Peter Ackroyd and Margaret Reynolds gave me information about Woolf that I didn’t know before. I learned, for instance, that Orlando was inspired by the family history of Vita Sackville-West, a fellow novelist and established poet who was also Woolf’s close friend and lover. She also published Woolf’s books through Hogarth Press. Anyway, Orlando started in the Elizabethan age where we meet the eponymous Orlando. Time and gender were relative in the story as it leapfrogged from one historical event to another, with Orlando reincarnated into either a female or a male. It was an interesting read and one that also challenges the boundaries of storytelling and what it can achieve.

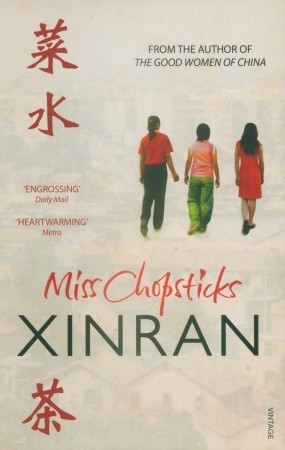

X: Xinran

Xinran’s Miss Chopsticks is the second novel by a Chinese writer I read this year. It was one of the random purchases I made last year when I realized how much I am lagging behind in Chinese literature. The first thing about the book that grabbed my attention was its title Apparently, In China, daughters were labeled as Chopsticks while sons were roof beams; chopsticks because women were seen as the weaker sex. The story starts in the Chinese province of Anhui where the three daughters of a peasant family moved to the city to earn money; their two oldest sisters were already married while the fourth born-daughter was blind and deaf. Daughters Three, Five, and Six, with the help of Uncle Two, traveled to Nanjing where they were employed by different but equally kind employers. There is not much action in the novel but the bond between the sisters was heartwarming to read. This was in direct contrast to the heartbreaking way women were seen by society. Reading the book, I thought that it was set in the 1970s or perhaps the 1980s. But no, it was set in the 1990s so it was even more appalling how women were still treated in contemporary China.

Y: Criselda Yabes

Before the month ended, I snuck another work of Philippine literature, Criselda Yabes’ Crying Mountain. This is the fourth novel written by a Filipino writer that I read this year. This is the most I read in a year. Yabes’ debut novel was even longlisted for the 2010 Man Asian Literary Prize. Crying Mountain recalls a historic event that even I have never heard of although the events following it I have an iota about. At the heart of the novel was the burning of Jolo in 1974, another tragic but pivotal chapter in the conflict-laden southern part of the country. The novel was a fictional account of the rise of the Moro National Liberation Front leader Nur Misuari and the ensuing rebellion he led. In response to this challenge, the Philippine military retaliated with violence. This historic event is often considered one of the integral incidents that gave rise to the Moro insurgency in the southern part of the country. These events were captured through the lives of an eclectic set of characters: Rosy Wright, a mestiza; Nahla, a Tausug girl dreaming of becoming famous; Professor Hassan, the rebel leader; and Captain Rodolfo, a soldier assigned at the Southern Command.

Z: Alejandro Zambra

During the first time I hosted Latin American Literature Month, one of the writers whose prose captivated me was the Chilean writer Alejandro Zambra. His Multiple Choice fascinated me for its unconventional structure. This made me want to read more of his works. The opportunity came when I recently encountered a copy of his latest novel Chilean Poet. Like The General in His Labyrinth, I was not planning on reading the book but I can’t keep the tenterhook. Chilean Poet charted the fortunes of Gonzalo Rojas, a poetry-loving teacher in Santiago who had a torrid love affair with his high school sweetheart Carla during the 1990s. They broke up only to reconnect nine years later. Carla now had a son, Vicente, with one of her previous lovers, Leon. At first, Vicente seemed like a dealbreaker for Gonzalo but they eventually formed a bond. Things turned south when, without Carla’s acquiescence, Gonzalo planned to move the family to the United States. He found Chile too indolent. What he did not expect was Carla’s vehement refusal to agree to the plan, prompting another separation. The second half of the novel focuses on eighteen-year-old Vicente and his relationship with Pru, an American journalist. Zambra was resplendent in adroitly weaving all of the novel’s various elements together. In Chilean Poet, he crafted an insightful read on family dynamics and filial relationships. At the same time, he probed into the maladies of modern Chile.

Considering that I just learned about this challenge today, I can say that I didn’t fare too bad. Imagine, I only missed out on one letter, Q. So woah. Happy reading everyone!

That’s some list. I can’t say I read everything, but good on you for taking on the challenge with such enthusiasm. 🙂

LikeLiked by 2 people

Doubly impressive given that you hadn’t officially signed up for the challenge but completed it anyway.

LikeLiked by 1 person