In Search of Spiritual Identity

In the ambit of Turkish literature, Elif Shafak has established herself as one of the leading voices of her generation. She is recognized globally as Turkey’s leading female novelist. Born on October 25, 1971, Shafak’s literary career commenced with the publication of Pinhan in 1998. It was critically received by readers and literary pundits alike and earned her the Rumi Prize, a Turkish literary prize. This set the tempo for an exceptional literary career. Her sophomore novel, The Gaze (Turkish title Mahrem), won the The novel won the Turkish Authors’ Association 2000 prize for “best novel.” In 2004, she made a shift to writing an English novel with the publication of The Saint of Incipient Insanities. The Bastard of Istanbul, her second novel originally written in English was longlisted for the Orange Prize.

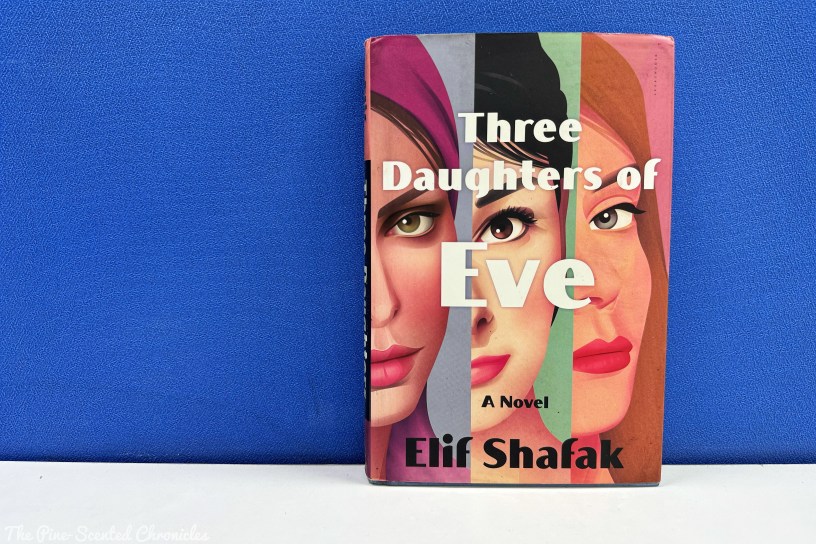

Among the twelve novels she published throughout her literary career so far is Three Daughters of Eve. Published in 2016, the novel commences in present-day Istanbul where the novel’s backbone, Nazperi Nalbantoğlu (Peri), was introduced. She was a wealthy housewife in her middle ages who, with her daughter, was on her way to meeting her husband at a lavish dinner party in a seaside mansion. On the way to the dinner party, Peri’s found herself being subjected to robbery and an attempted rape. In the ensuing struggle with the tramp attempting to wrest her bag, Peri notices a photograph fall from the bag, one she did not expect to see. While Peri was in the picture, it was the people flanking her – two women and a man – that left an impression on Peri, one that she would take with her as she managed to arrive at the dinner.

As the evening progressed, the ghosts of the photographs jolted Peri back to the past, particularly to her troubled childhood and the years she was studying in Oxford. Peri was born in Istanbul where she was raised by a conservative mother who was a devout Muslim and nationalist. However, her mother had very few words of inspiration or spiritual wisdom to share with her daughter. Meanwhile, Peri’s father was her mother’s antithesis. He was more liberal in his views and was an idealist. He openly questions the idea of God which thus creates tension in their household; he and his wife often get into heated arguments about God and the nature of religion. With the clashing spiritual ideologies surrounding her, Peri grew up confused about her spiritual identity. Her brothers also had contrasting ideas about life, religion, and their nation.

“Why did it have to be this way? Why did she not feel attracted to this boy, who was kind and personable, close to her in age and probably good for her? Instead it was the professor for whom she secretly yearned – a man not only old, unknown and unavailable, but also wrong. It puzzled her endlessly that she was not, and had never really been, interested in happiness – that magic word that was the subject of so many books, workshops and TV shows. She did not want to be unhappy. Of course, she didn’t. It just did not occur to her to seek happiness as a worthwhile goal in life. ”

~ Elif Shafak, Three Daughters of Eve

Peri’s beliefs and values were put to the test when she moved to Oxford to study; her father’s liberality made him push for his daughter’s education at Oxford University. For Peri, it was a cultural shift, Oxford’s quaint streets a stark dichotomy to the bustling metropolis that is Istanbul. It was also there that Peri met the two women with her in the photograph. The first one was Shirin, a faithless and sensual feminist with Iranian heritage; and Mona, a modest and devoutly religious Egyptian American. Mona, like Peri’s mother, was proud of her cultural and religious heritage. Together, the trio were the titular three daughters of Eve, with each representing different sides of the spiritual spectrum. Mona was the Believer, Shirin was the Sinner, and Peri was the one stuck in a quandary. Despite the glaring dichotomies in their beliefs. the three became best friends.

The three young women also shared a fascination for the charismatic Professor Azur; he was the fourth person and the only male in the photograph. Professor Azur taught a philosophy course aptly called “GOD.” He has a reputation on campus for his unconventional methods of teaching and his whimsical personality. Professor Azur’s class has a very liberal view of religion and only a handful of students are allowed in his class. His students represent various viewpoints and in class, they debated about a plethora of subjects, such as religion against faith, religiosity against atheism, and even justice and injustice. Professor Azur was coaxing his students to push the boundaries of their understanding of various facets of life, particularly through the lenses of faith and God. It was also through his class that the three young women crossed paths.

This places Peri at an impasse if not an interesting situation. Shafak did not hold back in immediately painting her profile. She was introduced as a “fine modern Muslim.” However, underneath this facade are cracks. The novel’s narrator alerts the readers that Peri will confront “the void in her soul.” To do so, Peri needed to travel back to the past to shed light on the various relationships that helped mold who she is in the present. The story shuttles between the past and the present as the past is integral in understanding the contemporary. She was surrounded by contrasting ideas. Her childhood, which occupied a healthy portion of the story, played a seminal role in Peri’s confusion. Her confusion extends beyond spirituality as she was also confronting her identity and even her cultural heritage.

From the confusion espoused by a household where contrasting perspectives clash, Peri’s years at Oxford were eye-openers. It was a step out of her comfort zone as she slowly gained valuable experiences and germane to this were Shirin and Mona. The contrasting opinions of the three women also caused constant arguments, akin to the debates Peri’s parents had at her home. Nevertheless, the three women learn to navigate these dire straits. Rather than letting these differences create a rift between them, their opposing views allowed them to forge a bond. Instead of wading through the sea of differences, they focused on their similarities. This close bond helped the three daughters of Eve in surviving their years at the university. It also opened possibilities for the three young women also experience romantic relationships.

“There are two kinds of cities in the world: those that reassure their residents that tomorrow and the day after, and the day after that, will be much the same; and those that do the opposite, insidiously reminding their inhabitants of life’s uncertainty. Istanbul is of the second kind. There is no room for introspection, no time to wait for the clocks to catch up with the pace of events. Istanbulites dart from one breaking news story to the next, moving fast, consuming faster, until something happens that demands their full attention.”

~ Elif Shafak, Three Daughters of Eve

Through Three Daughters of Eve, Shafak explored a plethora of subjects, the most palpable of which was religion and the nature of God. It is these two subjects that the novel revolves. Professor Azur was one of the vessels upon which the nature of God was explored and even confronted. He relentlessly pushed his students, including the three daughters of Eve, to grapple with the questions of faith, God, and, to some extent, politics. These interesting discourses challenge Peri’s views and the questions that plague many of us. Religion is indeed a complex subject. Finding one’s footing in it, as Peri experienced, was even doubly challenging. Shafak vividly lays out all of these difficulties we encounter as we try to understand the very nature of religion.

A source of confusion vis-a-vis religion is the contrasting views surrounding us. In Peri’s case, her parents figure prominently in her journey because they represent opposing views. She grew up with a skewed view of her own spiritual identity. Peri’s childhood years also explored family dynamics, emphasizing the existence of differing views living under the same umbrella. Families, while the most basic unit of society, are complex and can even be ambiguous. Peri’s father also had to grapple with his own demons; he has a proclivity for alcohol. Meanwhile, the matriarch had to deal with the radicalization of her children; the dangers of religious radicalization were subtly woven into the novel’s lush tapestry. Some of her children were also imprisoned. These were exacerbated by the patriarchal society she was raised in. It was in her devotions that she found solace, a reality many can relate to.

In Oxford, neither Mona nor Shirin presented any reprieve from her confusion. However, in the development of their bond, the Sinner and the Believer offered the Confused alternatives: acceptance, friendship, and loyalty. Like all friendships, theirs got tested. Through this eclectic cast of characters and their contrasting views, the novel underscored the different layers of secularism and the piety of religious practices. The characters’ contrasting views also underlined the struggles between modernity and liberal ideologies and conservatism and traditions. The characters also encountered impasses where they had to breach boundaries. As the lines between these views are blurred because of doubts and uncertainties, we sometimes have to make tough calls. Should we cross these boundaries?

“The impression she left on others and her self-perception had been sewn into a whole so consummate that she could no longer tell how much of each day was defined by what was wished upon her and how much of it was what she really wanted. She often felt the urge to grab a bucketful of soapy water and scrub the streets, the public squares, the government, the parliament, the bureaucracy, and, while she was at it, wash out a few mouths too. There was so much filth to clean up; so many broken pieces to fix; so many errors to correct. Every morning when she left her house she let out a quiet sigh, as if in one breath she could will away the detritus of the previous day.”

~ Elif Shafak, Three Daughters of Eve

While the novel examined subjects that reverberate on a universal scale, there was undoubtedly a Turkish touch to it. The modern Turkish attitudes toward these subjects, driven by the influences of the West, were capably captured by Shafak. Shafak’s heritage – she had a Turkish bloodline but spent most of her adult years in the West – places her at a pivotal juncture that allows her to examine both sides of the coin. This was further illustrated as the evening progressed and reached its inevitable conclusion. It was a swirl of discourses where Shafak also provided commentaries about the follies of academics and the bourgeoisie. On the backdrop was Turkey’s turbulent past. The 1980s military coup was referenced in the story. She also painted a portrait of life during military rule where torture and forced incarceration of individuals whose views do not align with the regime were ubiquitous. These horrible acts have adversely impacted the lives of the Turkish denizens.

The novel, without a doubt, was lush and intricate. Shafak does a wonderful job of weaving the novel’s various elements and it takes a while before its flaws start to manifest. While she raised relevant questions about faith, Shafak does not provide clear answers to these questions, or even semblances of resolutions considering that spiritualist Professor Azur, who was pivotal in Peri’s story, also came across as arrogant. The story also dragged in parts and it was too fixated on Peri’s childhood while falling short in exploring the interesting dynamics of the friendship of the three daughters of Eve. The story also dragged in some portions. Shafak redeemed herself by introducing psychologically complex characters who were not monochromatic and whose personalities provided the story with diverse textures and complexions.

For all its flaws, Three Daughters of Eve is still an insightful story about our own doubts and uncertainties, emphasizing questions about the nature of God, faith, and religion. The novel, however, does not reduce itself to a mere exploration of spirituality and religion. The Peri and the characters surrounding her, the story explored contrasting views on liberal politics and traditional values; and secularity and orthodox religious views. Three Daughters of Eve is also about history, the dynamics of families, the follies of academia, and the intricacies of friendship and romantic relationships. It is also Peri’s coming-of-age story. Three Daughters of Eve is a multifaceted and multilayered story from one of the contemporary’s most accomplished writers.

“She said, there’s something about love that resembles faith. It’s a kind of blind trust, isn’t it? The sweetest euphoria. The magic of connecting with a being beyond our limited, familiar selves. But if we get carried away by love or by faith, it turns into a dogma, a fixation. The sweetness becomes sour. We suffer in the hands of the gods that we ourselves created.”

~ Elif Shafak, Three Daughters of Eve

Book Specs

Author: Elif Shafak

Publisher: Bloomsbury

Publishing Date: 2017

Number of Pages: 367

Genre: Literary

Synopsis

They were the most unlikely of friends. Three young women with utterly different worldviews. They were the Sinner, the Believer and the Confused.

Peri, a married, wealthy, beautiful Turkish woman, is on her way to a dinner party at a seaside mansion in Istanbul when a beggar snatches her handbag. As she wrestles to get it back, a photograph falls to the ground – an old Polaroid of three young women and their university professor. A relic from a past – and a love – Peri has tried desperately to forget.

Three Daughters of Eve is set over an evening in contemporary Istanbul, as Peri arrives at the party and navigates the tensions that simmer in this crossroads country between East and West, religious and secular, rich and poor. Over the course of the dinner, and amidst an opulence that is surely ill begotten, terrorist attacks occur across the city. Competing in Peri’s mind, however, are the memories invoked by her almost-lost Polaroid, of the time years earlier when she was sent abroad for the first time to attend Oxford University. As a young woman there, she had become friends with the charming, adventurous Shirin, a fully assimilated Iranian girl, and Mona, a devout Egyptian American. Their arguments about Islam and feminism find focus in the charismatic but controversial Professor Azur, who teaches divinity but in unorthodox ways. As the terrorist attacks come ever closer, Peri is moved to recall the scandal that tore them all apart.

Elif Shafak is a bestselling novelist in her native Turkey, and her work is translated and celebrated around the world. In Three Daughters of Eve, she has given us a rich and moving story that humanizes and personalizes one of the most profound sea changes of the modern world.

About the Author

To learn more about Elif Shafak, click here.