In Search of Genuine Connections

For the longest time, Japanese literature – at least in the Anglophone-speaking world – has been dominated by male writers. The three Nobel Laureates in Literature produced by Japanese literature are all men: Yasunari Kawabata (1968), Kenzaburō Ōe (1994), and Kazuo Ishiguro (2017). They are flanked by a cast of equally talented albeit mainly male writers such as Shūsaku Endō, Yukio Mishima, Osamu Dazai, Jun’ichirō Tanizaki, Natsume Sōseki, and Ryūnosuke Akutagawa. Collectively, their works have defined the landscape of Japanese literature, particularly in the 20th century. They have written novels, short stories, and even poems that are revered in Japan where they are considered classics. Their works have also transcended physical borders as their influences are ubiquitous, earning them accolades worldwide.

Quite ironically, one of Japan’s most renowned works, Tales of Genji, was written by a woman, Lady Murasaki Shikibu. But despite this dichotomy, prominent female voices have riddled the vast landscape of Japanese literature. Sawako Ariyoshi and Fumiko Enchi are among the most decorated female writers who also thrived during the 20th century. Toward the end of the 20th century, a growing list of female Japanese voices was introduced to the global scene, led by popular and highly acclaimed writers like Yōko Ogawa, Yōko Tawada, and Banana Yoshimoto. They have become household names, both in Japan and globally. More recently, a new generation of female writers has slowly gained global recognition. This group includes Mieko Kawakami, Hiromi Kawakami, Hiro Arikawa, and Sayaka Murata. Their critically acclaimed works are testaments to Japan’s literary excellence.

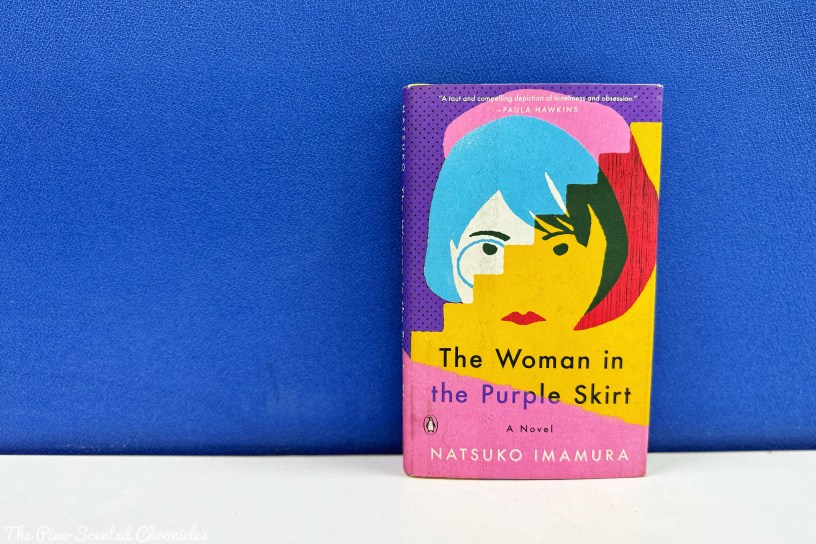

Joining the growing list of contemporary Japanese female writers whose works have been made available for Anglophone readers is Natsuko Imamura. Her novel, The Woman in the Purple Skirt, is an addition to many Japanese works translated into English tackling the Japanese female experience in modern Japanese society. Originally published in 2019 in Japanese as むらさきのスカートの女 (Murasaki no sukaato no onna), the novel won the prestigious Akutagawa Prize in the same year. Two years later, it was translated into English by Lucy North. At the core of the novel is an anonymous woman who simply refers to herself as the woman in the yellow cardigan; she conveys the story from her point of view.

“Once they had finished the apple, the Woman in the Purple Skirt and the children began to play a game of tag. This was the first time the Woman in the Purple Skirt had ever been made a member of the children’s little gang. The game of tag continued on and on, till well after nightfall, and each and every one of them had a go at being “it”.”

~ Natsuko Imamura, The Woman in the Purple Skirt

The woman in the yellow cardigan is essentially a social outcast. She is ignored by society and her peers. Nevertheless, she lurks in the shadows, always observing but rarely at the heart of the action. She was content living in relative obscurity. However, her life started to unravel with the entry of the eponymous woman in the purple skirt. When they became neighbors, the woman in the purple skirt immediately caught the narrator’s attention. The woman in the purple skirt is shrouded in a veil of enigma. What made her stand out was the purple skirt that she never seemed to take off. She also lived by herself. What further caught the attention of the narrator and their other neighbors was the routine she follows through to the hilt every day. Unbeknownst to her, she was being observed by her neighbors.

As part of her routine, Hino – the titular woman in the purple skirt – would buy a single cream brioche. She would then proceed to the park in the unnamed Japanese city where the novel is set. At the park nearby where they lived, she occupied the same bench; it was familiarly referred to by the narrator as an Exclusively Reserved Seat. While she eats her bread, the local children taunt her. Fascinated by her, the children competed for her attention. All the while, the woman in the yellow cardigan observes her undetected. The narrator notices what the woman in the purple skirt eats, where she goes, what she does, and who she interacts with. The narrator wanted to establish a friendship with the woman she had been observing. With the narrator’s attention on her subject, the reader shifts from the woman in the purple skirt to the woman in the yellow cardigan.

To win her over, the narrator discreetly lured the eponymous character to a job; the woman in the purple skirt was palpably in and out of jobs. By “subtly” dropping hints and placing highlighted employment books where the woman in the purple skirt can find them, the narrator is able to indirectly refer Mayuko Hino to the same cleaning agency she works for. Coincidentally, the two women got assigned to the same hotel where they were both tasked to perform housekeeping. It was at this juncture that things started to unravel between the two women. At first, Hino was timid but she eventually proved herself to be a capable worker. This scratches the surface. The narrator’s stalking of Hino started to become more serious. With the two women working together in the same place, the space between them grew smaller, thus, further fueling the woman in the yellow cardigan’s obsession.

As the yellow woman in the cardigan obsesses about the woman in the purple skirt, the attention shifts to her. Was it really a friendship that she wanted to establish with Hino? What drove her growing obsession? At the core of the narrator’s story is one of the key drivers of Japan’s social issues. In a high-functioning society like Japan, competitiveness is the key to survival. On the flip side, this drove an epidemic of loneliness. Everyone yearns for meaningful connections and to maintain them, similar to the case of the woman in the yellow cardigan’s case. She has been ignored by society at large. This, however, did not preclude her from wanting to be noticed, to be recognized, and to be seen, in particular by the woman in the purple skirt. It was a simple albeit lonely yearning.

“Some people would pretend they hadn’t seen her, and carry on as before. Others would quickly move aside, to give her room to pass. Some would pump their fists and look happy and hopeful. Others would do the opposite and look fearful and downcast. (It’s one of the rules that two sightings in a single day means good luck, while three means bad luck.)”

~ Natsuko Imamura, The Woman in the Purple Skirt

Japan’s epidemic of loneliness is driven by a plethora of factors. Some of these factors were elucidated in other contemporary literary works. Mizumi Tsujimura’s Lonely Castle in the Mirror explores the futoko who is described as a child who decides to stop attending school for an extended period due to mainly bullying or family issues. They become social recluses. Socially awkward individuals have become a norm in Japan; the Japanese have even coined a term for them: hikikomori. Imamura probes deeper into the other factors driving this growing social concern. Among these factors is the pressure placed by Japanese society on its denizens to conform to its highly and strictly regimented social norms. Those who refuse to conform to these norms are often frowned upon.

Conformity, however, does not guarantee social acceptance, such as in the case of the woman in the yellow cardigan. Meanwhile, the woman in the purple skirt was locked down by everyone because of her inability to keep a job or settle on a career. This goes against the grain of the highly competitive Japanese market. Even the woman in the yellow cardigan expressed her irritation about Hino’s questionable work ethic. The dangers of non-conformity were further underlined once Hino started working at the hotel. Hino’s choices and preferences – these mainly deviated from her co-workers – were scrutinized. These were captured through seemingly simple but astutely crafted dialogues. It was brilliantly done that a conversation about Hino’s preference not to use hotel shampoo transformed into a subtle discourse on workplace conformity. It is also a sugarcoated attempt to impose conformity.

Imamura’s vivid depiction of the workplace was one of the novel’s strongest achievements. She was able to capture the culture that exists in the modern Japanese workplace. She was incisive in dissecting the intricacies of the workplace, with particular emphasis on the workplace culture vis-à-vis women. The pressure for conformity to the workplace culture was exacerbated by contemporary society’s unrealistically high standards for women’s bodies and beauty. This can create a hostile and toxic working environment that pits one colleague against the other. When it was observed that one of the workers was receiving favorable treatment from their boss, a rumor about an affair involving the boss and the worker started to escalate. This rumor turned everyone against their fellow worker. Her colleagues were quick to criticize her work and shun her character. The level of toxicity at the workplace further drives the epidemic of loneliness.

The novel also underscored the power dynamics prevalent in the workplace which is often the driver for the exploitation and abuse of subordinates by those who are in charge of them. As such, Imamura subtly highlights the glaring dichotomies that persist between social classes. The members of the working class were mainly nameless and faceless while those who were in charge were given real names apart from their job titles, e.g. Supervisor. For the working class, job security is rarely assured, especially with the limited professional opportunities. Adding a layer of quirk to the story was how the novel’s two main characters were stripped of the article of clothing they were mainly wearing. This is how they are physically projected to the rest of the world, making them resonate universally. They can be anyone and their experiences can be experienced by anyone.

“As of now, I haven’t seen any sign of threatening letters posted on the Woman in the Purple Skirt’s apartment door. Nor have I noticed anyone who appears to be her landlord staking out her building, waiting and watching for her to come home. At night I see the lights go on in her place, and the dial on her gas meter appears to be steadily ticking over. She must be managing to pay her rent, and her electricity and heating bills.”

~ Natsuko Imamura, The Woman in the Purple Skirt

On the surface, the book tackles the intricacies of the workplace. However, it does not reduce itself to a mere workplace story. The story reverberates beyond the ambits of the workplace as the novel captures how sexual violence permeates the lives of women. Hino, for instance, experienced being groped from behind while riding the bus. This is a reality that women, not only in Japan but across the world, has to confront. This experience left Hino traumatized, thus, she ultimately avoids taking the bus. Interestingly, it was the woman in the yellow cardigan who loomed above the story; the woman in the purple skirt remained a cipher and was observed primarily through the lens of the narrator; the woman in the yellow cardigan, seen from a different lens, was a manipulator. While the novel can make for a compelling read, it can also careen toward the bizarre. While the plot is thin, Imamura makes up for her clear and accessible writing driven by a deadpan narrator.

Overall, Imamura’s The Woman in the Purple Skirt is a compulsive read despite being deceptively slender. Physical appearances can be deceiving, after all, as the story has proven. For her award-winning novel, Imamura builds on a relevant and timely subject. While it is laced with local flavor, it cannot be stressed enough how they resonate globally. The toxic workplace culture, the persistent sexual violence women experience both within and outside of the workplace and the glaring dichotomies between the classes are all captured in The Women in the Purple Skirt. These are also drivers for the epidemic of loneliness that pervades contemporary Japanese society. It is a novel where the bizarre converges with confusing and delightful moments. The winner of the prestigious Akutagawa Prize, The Women in the Purple Skirt is a worthy addition to a growing list of workplace novels capturing the complex intersection of workplace culture and femininity

Book Specs

Author: Natsuko Imamura

Translator (from Japanese): Lucy North

Publisher: Penguin Books

Publishing Date: 2021 (2019)

No. of Pages: 216

Genre: Literary

Synopsis

Almost every afternoon, the Woman in the Purple Skirt sits on the same park bench, where she eats a cream bun while the local children make a game of trying to get her attention. Unbeknownst to her, she is being watched – by the Woman in the Yellow Cardigan, who is always perched just out of sight, monitoring which buses she takes, what she eats, whom she speaks to.

The Woman in the Yellow Cardigan lures the Woman in the Purple Skirt to a job as a housekeeper at a hotel, where she too is a housekeeper. Soon, the Woman in the Purple Skirt is having an affair with the boss and all eyes are on her. But no one knows or cares about the Woman in the Yellow Cardigan. That’s the difference between her and the Woman in the Purple Skirt.

Studiously deadpan and chillingly voyeuristic, The Woman in the Purple Skirt explores envy, loneliness, power dynamics, and the vulnerability of unmarried women in a taut, suspenseful narrative about the sometimes desperate desire to be seen.

About the Author

Imamura Natsuko (今村 夏子) was born on February 20, 1980, in Hiroshima, Japan. To attend university, she moved to Osaka. Imamura’s first story was Atarashii musume (あたらしい娘, New Girl), a novella she worked on while working a temporary job. The novella won the 26th Dazai Osamu Prize in 2010. The story was eventually published with her short story Pikunikku (Picnic) in one volume under the new title Kochira Amiko (こちらあみ子, Amiko Here). The volume won the 24th Mishima Yukio Prize.

Imamura would receive more accolades for her work. Ahiru (あひる, 2016) was awarded the 5th Kawai Hayao Story Prize. Ahiru was also nominated for the 155th Akutagawa Prize, her first nomination for the prestigious literary prize. Her second nomination was for Hoshi no ko (星の子, Child of the Stars, 2017) which won the 39th Noma Literary New Face Prize. In 2019, Imamura made a breakthrough in the Akutagawa Prize after her novel Murasaki no sukaato no onna (むらさきのスカートの女, The Woman in the Purple Skirt) won the 161st Akutagawa Prize.

Imamura currently lives in Osaka with her husband and daughter.