A Long-Awaited Comeback

Life has its interesting detours. Take the case of Abraham Verghese, an American physician, professor, and successful writer. Verghese was born in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia the second of three sons to Indian parents. His parents were recruited by Emperor Haile Selassie to teach in Ethiopia. In Ethiopia, he started his medical training before moving to the United States to join his parents following the civil war that culminated with the deposition of the Emperor. In the USA, he pursued his training to be a doctor, primarily working as an orderly in a series of hospitals and nursing homes. He completed his medical studies in his native India at the Madras Medical College and was awarded a Bachelor of Medicine degree from Madras University in 1979. He then returned to the United States as one of many foreign medical graduates. The opportunities for foreign medical graduates, however, were limited. Verghese found work only in obscure hospitals and communities.

Among his seminal experiences as a young doctor was witnessing the development of the AIDS pandemic and providing care for terminal AIDS patients in the 1980s. Not only was it an eye-opener but it was also transformative. He would write a seminal scientific paper. However, the language of the paper was too clinical, too detached from the realities he witnessed. It was a language bereft of life, an antithesis of the lives of the patients he cared for. They did not justify their lives nor do they fully capture the swirl of emotions Verghese felt while caring for them. This Eureka moment prompted him to pursue a different path, that of being a writer. Taking a break from the practice of medicine, he enrolled at the Iowa Writers Workshop where he completed his Master of Fine Arts in 1991. In 1994, he published his first book, My Own Country: A Doctor’s Story, a literary montage of his experiences as a physician.

Despite his shift, Verghese remained highly involved in the field of medicine. He was a professor of medicine and chief of the Division of Infectious Diseases at Texas Tech Health Sciences Center in El Paso, Texas, and is currently the Linda R. Meier and Joan F. Lane Provostial Professor of Medicine, Vice Chair for the Theory & Practice of Medicine, and Internal Medicine Clerkship Director at Stanford University Medical School. In 2002, he was a founding director of the Center for Medical Humanities and Ethics at the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio. For his contributions to the field of medicine, he was awarded by President Barack Obama with the National Humanities Medal in 2015.

“Even if everyone knows her story, no one really knows how she feels. It pours out now: her rage, her shame, her guilt – it still lingers. But with the telling comes a sense of empowerment. She has no culpability in the Brijee matter. None, other than being naive and being a woman. During the inquiry she had tapped into the righteousness that was her due; she slapped down the least suggestion that she might be a fault. She had learned a lesson: to show weakness, to be tearful or shattered didn’t serve her. One shouldn’t just hope to be treated well: one must insist on it.”

~ Abraham Verghese, The Covenant of Water

The Mysterious Condition

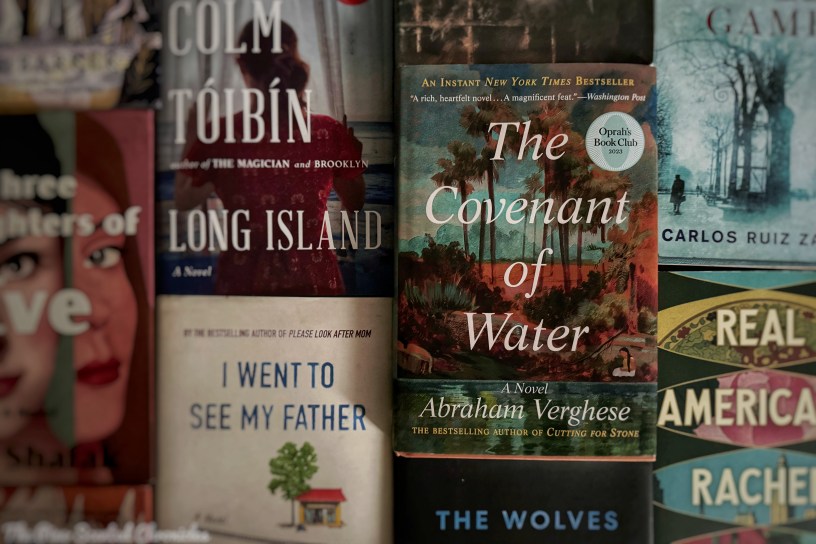

His successes in what he referred to as his first love came with parallel successes in his career as a writer. In 1998, he published The Tennis Partner, his second work of nonfiction. In 2009, he made a shift toward prose with the publication of his debut novel, Cutting for Stone. Like his earlier published work, his debut novel was warmly received by the general reading public and literary pundits alike. It was even shortlisted for the 2009 Wellcome Book Prize. It was a literary sensation that catapulted Verghese further to global recognition. Unfortunately, it took time before he would write his second novel. Nearly a decade and a half after his first novel, he made his long-awaited literary comeback in 2023 with The Covenant of Water, a novel inspired by the history of his mother’s family.

The Covenant of Water commenced at the turn of the century South Indian countryside. 12-year-old Mariamma was wedded off to a forty-year-old widower called Big Appachen in an arranged marriage. Mariamma recently lost her father but she was not given the time to grieve. As part of tradition, she left her family immediately and moved to the town of Parambil in Kerala where her husband’s family lived. Further, Mariamma’s mother will be taken in by their relatives but their relatives cannot take in Mariamma. Finding herself a mistress to a 500-acre estate, Mariamma was overwhelmed but slowly adjusted to her new role as a married woman. Initially, she felt isolated and yearned for her mother. Under the tutelage of the kind cook Thankamma, she learned to embrace her new role. Her husband was also initially distant and was mainly focused on earning a living for his family.

Mariamma soon learned that her husband’s family has a unique affliction. She would call it “the Condition.” Nearly every generation of her husband lost at least one member due to drowning. The circumstances are often suspicious. Mariamma then understood the reason for her husband and stepson’s irrational dislike of water. Contrary to expectation, Mariamma’s marriage started to flourish. Big Appachen began to understand his wife’s needs. Meanwhile, Mariamma became particularly close to her stepson JoJo and even considered him her own. JoJo gave his stepmother the nickname Big Ammachi (Big Mother). However, the affliction strikes at the most inopportune moment, leaving Mariamma aching. Mariamma’s cross to bear was doubled when her daughter Baby Mol was born with developmental disabilities. Nevertheless, Mariamma cherished her daughter. A son named Philipose was also born to the couple.

Alternating with Mariamma’s story is the story of Dr. Digby Kilgour. Orphaned at a young age, Digby was born and raised in Glasgow, Scotland. He was a talented surgeon but enlisted enlists in the Indian Medical Service and moved to Madras, India. His Catholic faith also barred him from gaining relevant training in his native Scotland. But like Mariamma, his life was struck with tragedy. An affair he had with Celeste Arnold, his mentor’s wife, took a darker turn. One night, while they were sleeping, a candle that was knocked over caused a fire that burned his bedroom. Celeste perished in the fire. To save his lover, Digby damaged his hands. The damage was irreparable which means that his talent as a physician is laid to waste. To recuperate, he stayed in a leprosarium run by Dr. Rune Orqvist. Rune also tried to repair his colleague’s hands but with little success.

“Every tree had its own personality. Their sense of time is different. We think they’re mute, but it’s just that it takes them days to complete a word. You know in the jungle I understood my failing, my human limitation. It is to be consumed by one fixed idea. Then another. And another. Like walking the straight line. Wanting to be a priest. Then a Naxalite. But in nature, one fixed idea is unnatural. Or rather, the one idea, the only idea is life itself. Just being. Living.”

~ Abraham Verghese, The Covenant of Water

With no other recourse, Digby decided to become a gentleman farmer. He invested in an estate he called Gwendolyn Gardens after his mother. As the story moved forward, Digby inevitably crossed paths with the denizens of Parambil. Elsie, the young daughter of Rune’s friend, assisted with Digby’s rehabilitation by teaching him to draw. It was at the leprosarium that Philipose, the son of Mariamma and Big Appachen, intersected with Elsie and Digby. A thirteen-year-old Philipose brought a choking boy to the leprosarium; Parambil had no proper medical facility. With Digby instructing Philipose on what to do, the young boy performs a tracheotomy to save the choking boy’s life. Eventually, Philipose became a celebrated writer while Elsie became an artist. The two got married. The novel then charted the fortunes of the descendants of Mariamma and their inevitable interaction with Digby.

The Indian Cultural Condition

Spanning seven decades, The Covenant of Water is a multilayered novel with each layer unpeeled as the story moves forward. At the onset, the novel vividly captures several facets of Indian culture. For one, the novel captured arranged marriages and child brides. Like in most societies, young women lack agency at a young age. Arranged marriages, unfortunately, remain prevalent in the present despite the idealization of romantic love in various facets of social media. Several works of contemporary literature captured the landscapes and the dynamics of arranged marriages, not only in Indian society but also in other parts of the world. While some don’t work, some also work, like in the case of Mariamma and Big Appachen. Beyond arranged marriages, the novel explores family dynamics within the ambit of the Indian household and, to a wider extent, gender norms within Indian society.

It is largely patriarchal, with the patriarch tasked with earning the household income and the matriarch looking after the household. Indian households are also steeped in tradition. Family histories and legacies are often intertwined with curses and superstitions. The Condition Mariamma referred to is an example, with the family’s affliction documented in a family tree called The Water Tree. Superstition also dictated the lives of the family. Cognizant of the Condition, Big Appachen and JoJo skirted around bodies of water lest they suffer the same fate as their ancestors. One of the elements that bound the characters together was love which was another prevalent element. It came in various forms such as romantic love. Filial love was also captured by the story; JoJo and Mariamma’s relationship, in particular, was heartwarming. On the sly, the novel captured instances of loyalty and friendship.

One significant theme explored in the novel is the caste system. It loomed above the lives of the characters, a natural law. Their silent adherence to tradition further emphasized the fault lines lying underneath the surface. The book highlighted the origins of the system and how it created divisions, both implicit and explicit, between various members of Indian society. This was demonstrated in the story of Shamuel, Big Appachen’s friend who was also a member of the pulayar caste. In Kerala, the caste system is different from the rest of India which observed the four ladders of caste hierarchy: the Brahmins, Kshatriyas, Vaishya, and Shudras. The caste system among Indian Christians emanated from Kerala. Religion, particularly Christianity, was also subtly woven into the reach tapestry of the novel. It was in her faith that Mariamma clang to during the early years of her marriage.

“Such precious, precious water, Lord, water from our own well; this water that is our covenant with You, with this soil, with the life You granted us. We are born and baptized in this water, we grow full of pride, we sin, we are broken, we suffer, but with water we are cleansed of our transgressions, we are forgiven, and we are born again, day after day till the end of our days.”

~ Abraham Verghese, The Covenant of Water

The Human and Physical Conditions

The Covenant of Water is also a vivid depiction of the cycle of life. Moments of triumph came with moments of sorrow and grief. People come and go. In providing intimate glimpses into the characters’ lives, Verghese vividly painted the intricacies of quotidian existence while painting the characters’ psychological profiles. Interestingly, the novel follows three individual threads, that of Mariamma, Digby, and Rune. The dichotomies between them were stark and yet they were able to establish lasting connections. Their shared experiences, from their losses and griefs – tragedies abound the story – to their triumphs and breakthroughs underlined human connections. Connections with the other members of the community are as integral as connections established within the family. Like the waterways of Kerala, the characters were connected.

The legacies of colonialism added layers and textures to the story. After all, the story captured the years leading up to India’s declaration of independence and the years immediately following it. The colonizers’ exploitation of India was captured in the novel. Vestiges of their exploitation can be gleaned in several facets of contemporary Indian society. Ironically, the Western characters in the novel were far from the villains they are often portrayed as. Digby’s role was allegorical as he represented both the oppressor and the oppressed; his story underlined the class system in the United Kingdom, contrasting India’s own caste system. Digby and Rune’s presence also showed the interactions between the East and the West. The events of the novel were juxtaposed with seminal historical events shaking up contemporary India.

Before India declared independence, Indian soldiers were enlisted to fight during the Second World War. Social upheavals of the 20th century were captured in the story. These were backed by the statehood of Kerala, the victory of the communists during the election, the move towards socialism, and the insurgencies that persist. The Naxalite revolution was prominently featured in the latter parts of the story. Naxal originated from the village of Naxalbari in West Bengal where the Naxalbari uprising of 1967 took place. The Naxalites supported Maoist political ideologies. Verghese was particularly adroit in writing about the history of disease, medicine, and surgery in India. The novel was a vivid portrayal of the revolution of India’s attitude toward leprosy, childbirth, drug addiction, and afflictions that were beyond the ordinary, like the “Condition.”

The novel soared with Verghese’s writing. It was accessible and lyrical. The descriptive nature of his writing also created a sense of place that transported the readers to southern India. The topography was vividly captured by Verghese’s writing: Where the sea meets white beach, it thrusts fingers inland to intertwine with the rivers snaking down the green canopied slopes of the Ghats. It is a child’s fantasy world of rivulets and canals, a latticework of lakes and lagoons, a maze of backwaters and bottle-green lotus ponds; a vast circulatory system because, as her father used to say, all water is connected. These vivid descriptions were encapsulated in Verghese’s intricate descriptions of surgical procedures, anatomy, and even medical interventions.

“You see yourselves as being kind and generous to him. The ‘kind’ slave owners in India, or anywhere, were always the ones who had the greatest difficulty seeing the injustice of slavery. Their kindness, their generosity compared to cruel slave owners, made them blind to the unfairness of a system of slavery that they created, they maintained, and that favored them. It’s like the British bragging about the railways, the colleges, the hospitals they left us—their ‘kindness’! As though that justified robbing us of the right to self-rule for two centuries! As though we should thank them for what they stole!”

~ Abraham Verghese, The Covenant of Water

A Literary Masterpiece

The Covenant of Water is, without a doubt, a modern masterpiece. It is a literary accomplishment that soars with its vast coverage. The stories of Mariamma, Digby, and Rune, and their forebears intersected to produce a labyrinthine yet memorable read. Spanning seven decades, the novel casts a wide net over a plethora of subjects. In its distinct way, the novel was a window into the beauty of India, its colorful history, and the diversity of its people and culture. Its practices and traditions were woven into the novel’s rich tapestry. Superstitions and curses formed the mantle of the condition. This was exacerbated by the complications of the caste system and arranged marriages, and the legacy of colonialism. The social upheavals that riddled modern Indian history also formed an evocative backdrop for the story.

In its panoramic scope, the novel soars. This was complemented by the indomitable human spirit and the uncertainty of life. Triumphs came with struggles. Joys came with pains. Despite all of these, we remain resilient. We find strength in the connections we establish with those around us, those with whom we have shared experiences. It brims with hope. The Covenant of Water is the history of a family and of a country both unraveling at the turn of the century. They are forced to confront various elements as their surroundings transform and evolve. Parts historical fiction, parts family saga, and parts social commentary, Verghese’s sophomore novel is a lush tapestry deserving of all the accolades it received and underlining Verghese’s status as a literary star.

“And now that daughter is here, standing in the water that connects them all in time and space and always has. The water she first stepped into minutes ago is long gone and yet it is here, past and present and future inexorably coupled, like time made incarnate. This is the covenant of water: that they’re all linked inescapably by their acts of commission and omission, and no one stands alone. She stays there listening to the burbling mantra, the chant that never ceases, repeating its message that all is one. What she thought was her life is all maya, all illusion, but it is one shared illusion. And what else can she do but go on.”

~ Abraham Verghese, The Covenant of Water

Book Specs

Author: Abraham Verghese

Publisher: Grove Press

Publishing Date: 2023

No. of Pages: 715

Genre: Historical

Synopsis

A #1 national bestseller and an Oprah’s Book Club pick, The Covenant of Water is the long-awaited new novel by Abraham Verghese, the author of the major word-of-mouth bestseller Cutting for Stone, which has sold over 1.5 million copies in the United States alone and remained on the New York Times bestseller list for over two years.

Spanning the years 1900 to 1977, The Covenant of Water is set in Kerala, on India’s Malabar Coast, and follows three generations of a family that suffers a peculiar affliction: in every generation, at least one person dies by drowning – and in Kerala, water is everywhere. At the turn of the century, a twelve-year-old girl from Kerala’s Christian community, grieving the death of her father, is sent by boat to her wedding, where she will meet her forty-year-old husband for the first time. From this unforgettable new beginning, the young girl – and future matriarch, Big Ammachi – will witness unthinkable changes over the span of her extraordinary life, full of joy and triumph as well as hardship and loss, her faith and love the only constants.

A shimmering evocation of a bygone India and of the passage of time itself, The Covenant of Water is a hymn to progress in medicine and to human understanding, and a humbling testament to the hardships undergone by past generations for the sake of those alive today. Imbued with humor, deep emotion, and the essence of life, it is one of the most masterful literary novels published in recent years.

About the Author

Abraham Verghese was born on May 30, 1955, in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. He was the second of three sons born to parents of Indian origin; his parents were originally from Kerala and were recruited by Emperor Haile Selassie to teach in Ethiopia. Verghese grew up near a hospital. In Ethiopia, he also started his medical training but in light of the revolution and the deposition of the Emperor, Verghese joined his parents in the United States where he continued working in medical facilities. He then moved to India to complete his medical studies at Madras Medical College and was awarded a Bachelor of Medicine degree from Madras University in 1979.

Post-university, he returned to the United States as a foreign medical graduate seeking an open residency position. However, because of his status, his opportunities were limited. He worked in less popular hospitals and communities open to him. At Johnson City, Tennessee, he was an internal medicine resident from 1980 to 1983 then took up a fellowship at Boston University School of Medicine. He worked at Boston City Hospital for two years. There, he witnessed the early signs of the HIV epidemic. His interactions with HIV patients transformed him. He even wrote a scientific paper. However, the language and voice of a scientific paper did not fully convey what he felt nor did the paper capture the lives of the patients; he dealt with terminal cases. This made him interested in writing.

As his interest in writing grew, Verghese took a break from the profession he called his first love and studied at the Iowa Writers Workshop. In 1991, he earned his Master in Fine Arts, and in 1994, he published his first book, My Own Country: A Doctor’s Story (1994). The book earned him the Lambda Literary Award for Gay Men’s Biography/Autobiography. He published another memoir in 1998, The Tennis Partner. In 2009, he pivoted toward prose with the publication of his debut novel, Cutting for Stone. It was shortlisted for the Wellcome Book Prize. His sophomore novel, The Covenant of Water was released in 2023. His works have been featured in prominent publications such as the New Yorker, Texas Monthly, Atlantic, The New York Times, The New York Times Magazine, Granta, Forbes, and The Wall Street Journal, among others.

Despite his pivot toward writing, Verghese remained a prominent figure in the world of medicine. After graduating from the Iowa Writers Workshop, he became a professor of medicine and chief of the Division of Infectious Diseases at Texas Tech Health Sciences Center in El Paso, Texas. After 11 years, he left El Paso to serve as a founding director of the Center for Medical Humanities and Ethics at the University of Texas Health Science Center in San Antonio. In 2007, he joined Stanford University School of Medicine in 2007 as a tenured professor for the Theory and Practice of Medicine and Associate Chair of Internal Medicine. He is currently the Linda R. Meier and Joan F. Lane Provostial Professor of Medicine, Vice Chair for the Theory & Practice of Medicine, and Internal Medicine Clerkship Director.

For his works, Verghese received several accolades. In 2011, Verghese was elected a member of the Institute of Medicine. In 2014, he received the 19th Annual Heinz Award in the Arts and Humanities. President Barack Obama presented him with the National Humanities Medal in 2015. In 2023, he was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship. He was a Fellow of the Royal College of Physicians, Edinburgh, Royal College of Physicians, Edinburgh in 2014. He also received six honorary doctorate degrees.