Happy Wednesday everyone! Wednesdays also mean WWW Wednesday updates. WWW Wednesday is a bookish meme hosted originally by SAM@TAKING ON A WORLD OF WORDS.

The mechanics for WWW Wednesday are quite simple, you just have to answer three questions:

- What are you currently reading?

- What have you finished reading?

- What will you read next?

What are you currently reading?

How time flies! Just like that, we are two-thirds done with November. Time is quite in a hurry and sadly, there is no way for us to slow it down. Time keeps flowing, taking its natural course. This means we are inching closer to the conclusion of 2024 and the commencement of a new one. As the year draws to a close, I hope that the year has been kind to everyone. I hope everyone has completed their goals or is on track to achieving them. I hope that everyone gets repaid for their hard work. I hope the remainder of the year will shower everyone with blessings and good news. As I approach the final stretch of the year, my focus, reading-wise, has shifted to the remaining books in my reading challenges. This is nothing new considering how I have always scrambled toward the end of the year to catch up on my active reading challenges. With Adolfo Bioy Casares’ The Invention of Morel, I will be completing my 2024 Top 24 Reading List.

It was through online booksellers that I first encountered the Argentine writer who, I just learned, was the protégée of Jorge Luis Borges, a titan of Argentinian if not world literature. I guess I was right in including the book in my 2024 Top 24 Reading List. Besides, the book has been gathering dust on my bookshelf; I bought it five years ago. I just started the slender book and most of my understanding of it came from the Introduction; it was the book that elevated Bioy to fame. The novella takes the form of a journal written by an anonymous narrator. He was on the run and arrived on an abandoned island where he came to live alone. The recent visitors to the island contracted a mysterious sickness with symptoms resembling radiation poisoning. The anonymous writer’s fear of being caught, however, was stronger than his fear of contracting the same disease. I can’t wait to unlock the mysteries the story holds. I just might finish it tomorrow.

What have you finished reading?

The past week has been quite productive, in terms of reading at least. Despite focusing on my reading challenges, I managed to sneak in some books that were not part of the said challenges but I still wanted to read. Among the books that recently piqued my interest was Nawal El Saadawi’s God Dies by the Nile. It was actually just this month that I first encountered the Egyptian writer; Egyptian literature, for me, has become synonymous with Naguib Mahfouz so discovering other Egyptian writers is quite a pleasure for me. Besides, I learned that El Saadawi is quite the literary figure, not only in the ambit of Egyptian and Arabic literature but in world literature as a whole.

Referred to as the Simone de Beauvoir of the Arab world, El Saadawi is a prominent name in Arabic literature. God Dies by the Nile is set in Kafr El Teen, a village along the Nile. The situation there is dire. Peasants had no recourse but to toil the land for its meager harvests and occupy mud huts that jotted the river. What little they earn goes to food for the family. The story, however, pans beyond an exploration of social classes. At the heart of the story is Zakeya whose family is among those exploited by the oppressive patriarchal system. Members of her family were raped, falsely imprisoned, or disappeared. At the helm of this oppressive system was the town’s corrupt mayor, flanked by the town’s most influential: the Imam of the village mosque, the barber and local healer, and the Head of the Village Guard. The Mayor’s cronies also help him procure young girls. One of the girls who caught the mayor’s eyes was Nefissa, one of two daughters of Zakeya’s brother, a widower. The slender novel captures the level of moral corruption that permeates the Egyptian countryside, with politics as its crucible. I would have wanted the book to be longer but it was more than enough to provide me a glimpse into El Saadawi’s oeuvre, making me want to explore it further.

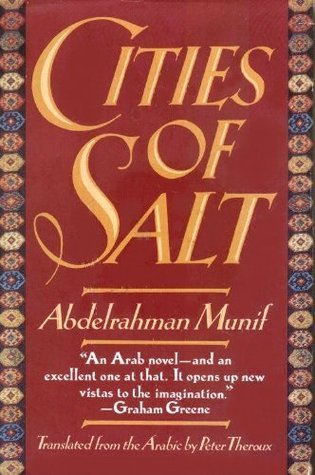

Like in the case of El Saadawi, I have never come across Abdelrahman Munif (عَبْد الرَّحْمٰن بِن إِبْرَاهِيم المُنِيف) before. It was during the height of the pandemic when I first came across him through an online bookseller. With my curiosity piqued, I obtained a copy of his novel Cities of Salt. This was notwithstanding the fact that I barely had any iota about the Arabian writer or what the novel was about. I was merely relying on my adventurous side as a writer. Besides, I can sense that the book and the writer will expound my reading horizon, making me venture into uncharted territories. I am always up for new adventures. Cities of Salt is the third novel originally written in Arabic in a row that I read.

Cities of Salt is also the twenty-third novel from my 2024 Top 24 Reading List I read. First published in Arabic in 1984, as مدن الملح (Mudun al-Milḥ), it is the first book of a quintet works of petrofiction; it is considered a hallmark of petrofiction. The novel transports readers to an oasis called Wadi Al-Uyoun situated in an unnamed country on the Persian Gulf. The village was home to the Atoub tribe and was helmed by Miteb Al-Hathal. The story’s main plot driver was the discovery of oil in the region in the early 20th century. With the discovery of oil came American interest; Munif vividly captured their entry into the Arabian countries. The villagers were bewildered. Slowly, the Americans’ presence became palpably permanent when heavy pieces of machinery and equipment entered the village. They were curious but also saw it as an ominous sign; the children even threw stones at the machine from a distance just to check out what it was. The locals’ irreverence and apprehension, however, were dismissed by the “invading” foreigners who proceeded with their plans. They drilled the ground and even built houses. Over the coming years, we see how the discovery of oil altered the village and in its stead, an urban center called Harran rose. But more than the discovery of oil, Munif explores how the Americans’ presence altered the landscape of Wadi Al-Uyoun and its neighboring towns, how modernization dismantled tradition, and the prominent role of politics and lobbying. Overall, Cities of Salt is an insightful and vivid story steeped in history. I hope I get to obtain the succeeding books in the quintet.

Wrapping up my three-book week was a more familiar name. I have been a fan of Nobel Laureate in Literature Gabriel García Márquez since I read One Hundred Years of Solitude nearly a decade ago. I have since read more of his works. This brings me to his latest translated novel, Until August. I was surprised when I heard of its release earlier this year. I think it is his first book to be published posthumously. It drew even more controversy when it was revealed that the book’s publication went against the Colombian writer’s wishes to destroy the manuscript after his death; the English translation was published on his 97th birthday. Regardless, the world – that includes me – was looking forward to the release of the book.

More details about how the book came to be were provided by the Editor in the Notes. It was originally planned to be a collection of four stories but circumstances did not allow García Márquez to complete it. His dementia also precluded him from following through with his plot. At the heart of the story was Ana Magdalena Bach. She was happily married to Doménico Amarís, the director of a musical conservatory, for nearly three decades. Things changed when, in her mid-forties, Ana Magdalena decided to make an annual pilgrimage. Every August, she travels to an unnamed Caribbean island in order to lay flowers on her mother’s grave. These travels were anything but uneventful. During her visits to her mother’s grave, she takes on a lover, usually one-night stands with strangers whom she was attracted to. This then became part of her annual pilgrimage. There are philosophical inquiries as Ana Magdalena grapples with her inner turmoil. Music plays a prominent role in the story; it is akin to reading a Murakami novel. The novel did remind me a bit of Memories of My Melancholy Whores because it probed into sex and aging; ironically, García Márquez shelved Until August to work on this novel. Interstingly, Until August is García Márquez’s first novel to have a female protagonist. I do agree with literary pundits, this is one of the Colombian writer’s minor works.

What will you read next?