Happy Wednesday everyone! Wednesdays also mean WWW Wednesday updates. WWW Wednesday is a bookish meme hosted originally by SAM@TAKING ON A WORLD OF WORDS.

The mechanics for WWW Wednesday are quite simple, you just have to answer three questions:

- What are you currently reading?

- What have you finished reading?

- What will you read next?

What are you currently reading?

Just like that, we are already in the second month of the year. How time flies! Regardless, I hope that your year is going the right way. I hope that 2025 will be a year of prayers answered and goals achieved. I hope it will usher in good news, healing, and prosperity. I hope that you are already making progress on your goals and targets. I fervently wish that everyone achieves their goals and even dreams this year. Personally, I have several goals this year in all facets of life. In reading and writing alone, I have lined up several already. For one, I already set my Goodreads goal to 100 books, the first time I am doing so from the onset. It is my goal to end the year with more translated books than books originally written in English. I am hopeful that I will be able to achieve them.

With this in mind, I commenced my reading year by immersing myself in the works of East Asian writers. My failure to a Japanese literature month last year, the first time in a while, was a main driver. Speaking of Japanese literature, I am currently reading Keigo Higashino’s The Miracles of the Namiya General Store. It was through works of crime and mystery fiction that I first came across Higashino. This is why Namiya General Store immediately piqued my interest. It is a deviation from his other works, at least from the cover and title alone. Little did I know that the main characters were, technically, delinquents. It was running from law that the trio Atsuya, Kohei, and Shota found themselves in the titular Namiya General Store. In the 1980s, the Store became popular with citizens after its owner, Yūji Namiya, accepted the local’s letters seeking advice for anything troubling them. Flash forward to 2012 and the trio found themselves in a similar position. The trio try to provide pieces of advice to random individuals who still dropped their letters. The fragmented structure that the novel employs is reminiscent of the recent trend of having individual stories, mostly thematically connected, comprise a whole novel. Overall, the story is getting more and more interesting as new characters are introduced.

What have you finished reading?

The past week has been less productive than the previous weeks. I only managed to complete two books. The primary reason for this is the heftiness of Otohiko Kaga’s Marshland. At over 800 pages, it is the longest book I read this year, so far. Before 2024, I had not heard of Kaga but the moment I encountered his novel during one of my excursions to the local bookstore, I knew I wanted to read it. Besides, I tend to gravitate toward lengthy books. It is this curiosity that prompted me to include the book to my 2025 Top 25 Reading List; it is the making it the second from the list I read after Ae-ran Kim’s My Brilliant Life.

The novel was originally published in 1985 but the increasing interest in translated works paved the way for its English release in 2024. Set in 1960s Japan, the central figure of Marshland is Atsuo Yukimori, a former soldier and convict now working as an auto mechanic. Despite his troubled past, he found peace although it meant living alone in Tokyo. The harmony of his life was disrupted by his acquaintance with Wakako Ikéhata, a university student he met while taking classes at the local skating rink. They forged an unusual friendship that everyone was critical of. Wakako was the daughter of a university professor. She was beautiful and brilliant but was mentally unstable. As Atsuo travels between Tokyo and Nemuro, his hometown, memories permeate the story. At the same time, Kaga was closing in on the crux of the story. In the late 1960s, Tokyo and other parts of Japan were rocked by student riots. The social upheaval sweeping Japan led to the rise of activism. Wakako, despite her mental frailties, found herself in the middle of one of these student protests, along with some members of the Q-Sect, a radical student organization. When a Shinkansen bombing incident on February 11, 1969, resulted in casualties, the authorities were quick to pin the accusation to Atsuo. The incident outraged the nation, making it imperative for a culprit, any culprit, to be found immediately. Unfortunately, Atsuo, with his criminal record, fits the bill perfectly. Wakako and several members of the Q Sect were also indicted on the charges. Atsuo was sentenced to death while the others were meted with sentences ranging from five years to life. Marshland is an intricate police procedural that is, despite its length, quite absorbing. It also exposes the corruption that permeates major institutions in the Japanese political structure. Overall, Marshland was a rewarding read that kept me at the edge of my seat.

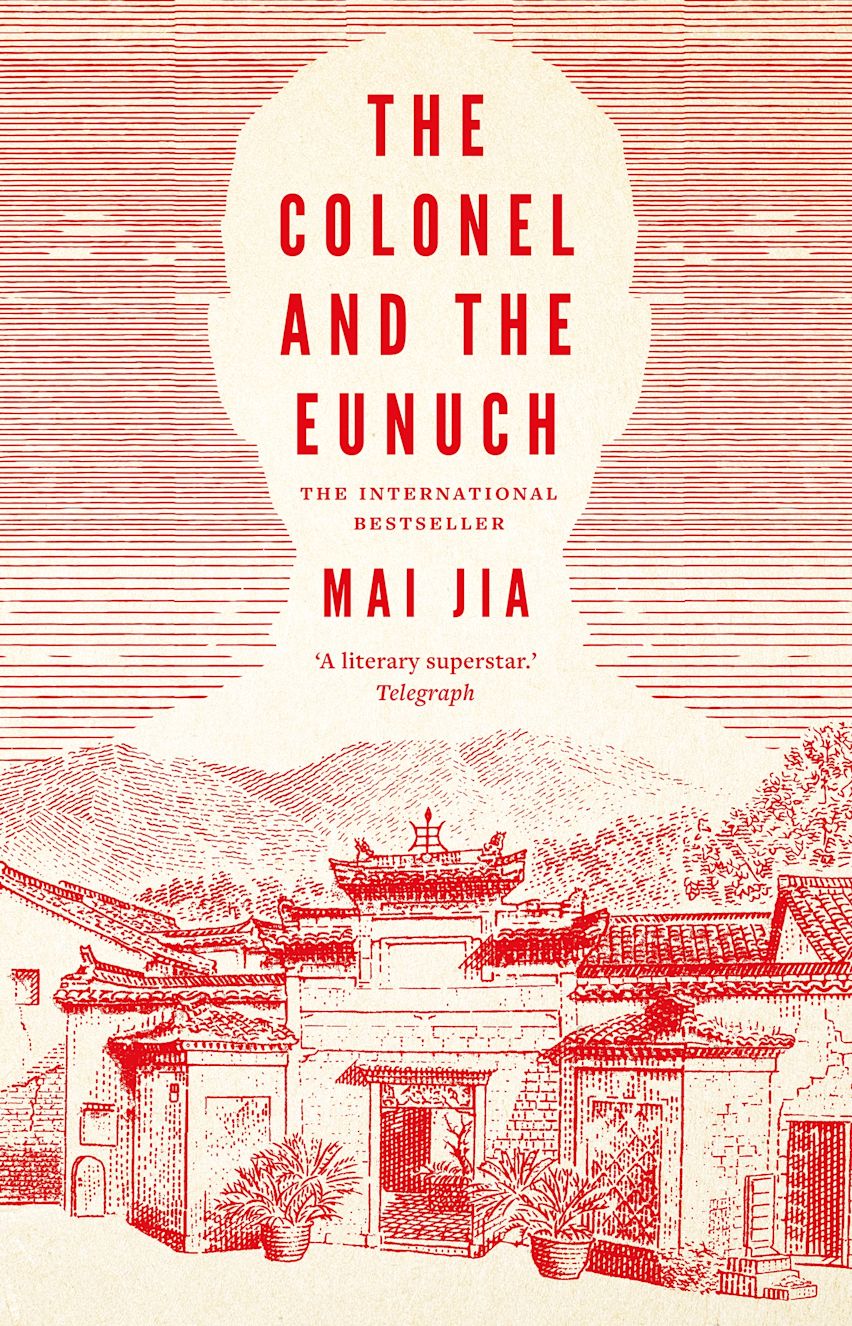

From Japan, my next read took me to the Mainland China. Admittedly, despite the extensiveness of Chinese literature and the vastness of its influence, it is one part of the literary world I have rarely ventured into. This is one of the primary reasons why I decided to start my 2025 reading journey with works of East Asian writers. I also admit limited knowledge on Chinese writers and had it not been for a random excursion to the local bookstore, I might have not encountered Mai Jia who, I learned, is quite a well respected figure in Chinese literary circles. I came across a copy of The Colonel and the Eunuch and my curiosity was piqued. Like Marshland, I included it to my 2025 Top 25 Reading List.

Originally published in 2019 as 人生海海, The Colonoel and the Eunuch transports the readers to the Chinese countryside of the 1960s. It is worth noting that majority of the works of Chinese writers I read so far are set in the countryside. The story is narrated by a boy who found himself fascinated by the novel’s central figure, the Colonel who the locals also referred to as the Eunuch. The boy’s father and the Colonel were childhood friends and even apprenticed together. The boy’s father, however, was overshadowed by the Colonel who was a quick-study. Their path diverged when the Colonel joined the army. When he returned home, he gained repute as a senior officer in both the Nationalist and Communist armies in China’s various wars and an eminent surgeon. Along with his repute is disrepute. Gossip abounded about what he has done during the war. Most of the locals resented the Colonel because in a village were conformance was mainstream, he deviates. Adding a layer of intrigue was his moniker Eunuch although none of the locals said it to his face. The teenage boy was nevertheless fascinated by the Colonel and his mysterious persona. As the story moved forward, the boy gets to hear and witness how the Colonel’s personal story gets told and retold. I am not a fan of the writing; perhaps this is due to the function of translation. Overall, The Colonel and the Eunuch is a riveting read that provided insights into Chinese society and history.

What will you read next?