Happy Wednesday everyone! Wednesdays also mean WWW Wednesday updates. WWW Wednesday is a bookish meme hosted originally by SAM@TAKING ON A WORLD OF WORDS.

The mechanics for WWW Wednesday are quite simple, you just have to answer three questions:

- What are you currently reading?

- What have you finished reading?

- What will you read next?

What are you currently reading?

How time flies! It is already the third week of February. In a couple of days, we will already be welcoming the third month of the year. How has your year been? I hope that the year is showering you with favors. I hope that 2025 will be a year of prayers answered and goals achieved. I hope that you are already making progress on your goals and targets. If not, it is still fine. Sometimes just simply making it through the day is enough. I fervently wish that everyone achieves their goals and reaches their dreams this year. Personally, I have several goals this year in all facets of life. In reading and writing alone, I have lined up several already. For one, I already set my Goodreads goal to 100 books, the first time I am doing so from the onset. It is my goal to end the year with more translated books than books originally written in English. I am hopeful that I will be able to achieve them.

To commence my reading year, I have been reading works of East Asian writers. This is driven by several factors, among them my foray into the works of Chinese writers. I have read four works of Chinese writers and am currently reading my fifth, S.I. Hsiung’s The Bridge of Heaven. This is now the most written work by Chinese writers I have read in a year. Anyway, The Bridge of Heaven is set in the Chinese countryside; this is no longer a surprise because most of the books written by Chinese writers I read so far were set in the countryside. I guess because the traditions and dynamics of small towns and villages are microcosms of the overall sentiment that permeates China. At the heart of the novel are brothers Li Ming and Li Kang who, following their parent’s demise, divided the family home in equal parts. They, however, were the antithesis of each other. Li Ming was the rational one while his younger brother was more spontaneous. The former was more hardworking while the latter is perceived to be lazy. The story gets more interesting when the brothers establish their families. This is just the start as the opening chapters of the novel laid out the landscape of the story. I will be sharing more of my impressions in this week’s First Impression Friday update.

What have you finished reading?

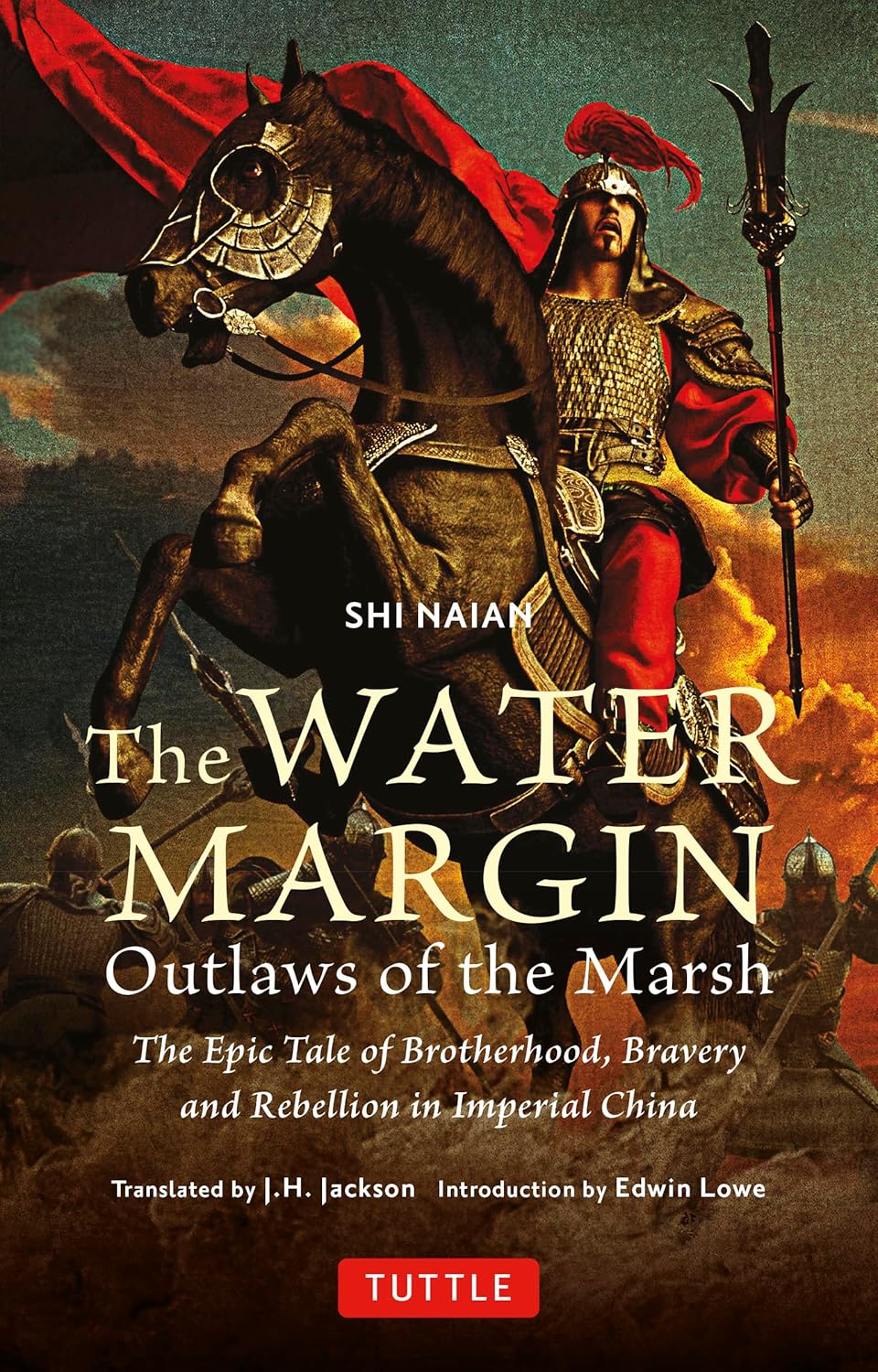

After a slow reading week, the past week has been quite productive. I was able to complete three books. The first of these three books was the reason for the slowdown in my reading momentum: Shi Naian’s The Water Margin. At nearly 800 pages, the book is rather thick. After Otohiko Kaga’s Marshland, it is the second-longest book I read this year. Further, I found the book daunting. It is one of the four classics of Chinese literature. This makes it the second book of the four I read; I read an abridged version of Cao Xueqin’s Dream of the Red Chamber during the first year of the pandemic. I am actually hitting several birds with one stone because The Water Margin is also listed as one of the 1,001 Books You Must Read Before YOu Die.

Originally titled 水滸傳 (Shuihu Zhuan), The Water Margin – or in some versions Outlaws of the Marsh or All Men Are Brothers – is one of the earliest novels originally written in vernacular Mandarin. When I started reading The Water Margin. I had very little inkling of what the book was about. Thankfully, the introduction provided me glimpses into what the book was about. The book introduces a vast cast of characters; almost Dickensian, The most prominent characters were the 108 outlaws-cum-demons released by Marshal Hong Xin during a visit to a Taoist monastery to seek a cure for a plague currently afflicting the denizens of Kaifeng, the Eastern Capital of the Song Dynasty. Slowly, the novel paints a vivid portrait of Song Dynasty China. Cities were governed by prefects who were abusive and corrupt. They were supported by equally corrupt generals. The vast cast of characters can be daunting although the novel focuses on a limited cast, including Lin Chong, Wu Song, and Song Jiang; Song Jiang is one of the leaders of the bandits. We each get to read about their experiences and how their lives were altered by the corruption, both moral, social, and political, that pervaded Chinese society. The outlaws all converged and established a stronghold in the fictional Liangshan Marsh (梁山泊) area, hence, the book’s title. The novel is quite eventful as it guides the readers across the landscape of Song Dynasty China. Rebellion was rife. Outlaws were either heretics or heroes. They cause the collapse of institutions or usher change. Overall, The Water Margin, despite some sloppy translations here and there and graphic details of violence, was a very gripping and memorable read, worthy of being called one of the four classics of Chinese literature.

My foray into the vast landscape of East Asian literature next took me to a very familiar territory. Without a doubt, Japanese literature has become one of my comfort zones and favorites in the ambit of literature. This interest in Japanese literature grew during the pandemic years. One of the things that I noticed about it is the proliferation of books that integrate cats. One of my earliest forays into the feline world of Japanese literature is Hiro Arikawa’s The Travelling Cat Chronicles. I loved the book. I also read Natsume Sōseki’s I Am A Cat which I consider the father of the cat novels. In the past two years, I have read even more cat books as more works of Japanese literature is being made available to Anglophone readers.

Joining this growing list of cat books is Syou Ishida’s We’ll Prescribe You a Cat which was originally published in 2023 as 猫を処方いたします。In a way, the novel shares parallels with other recent Japanese titles. Rather than straightforward prose, Ishida conjured several stories which are thematically interconnected. At the heart of the story Nakagyō Kokoro Clinic for the Soul, a clinic that caters to individuals who need healing. It reminded me of Funiculi Funicula, the popular café in Toshikazu Kawaguchi’s popular Before the Coffee Gets Cold series. Both are located in quaint and obscure locations and offer a resolution to those who are in want of them. However, while the café is accessible to everyone, the Kokoro Clinic only appears to those who are in dire need of help or are at a crossroads. The in-house doctor then prescribes a cat to them. On the surface, it is quite an unusual prescription that caught the characters off-guard. However, these cats were catalysts for the changes that would take over the characters’ lives. The diversity of the characters’ concerns – they suffered from the stresses of quotidian existence – make for a smorgasbord of heartwarming stories. One character had trouble at work while another one was grappling with change. Overall, We’ll Prescribe a Cat is a lighthearted story that reminds us to brace for the uncertainties of life.

From two new-to-me writers, my next read brought me back to a more familiar name. Osamu Dazai, born Shūji Tsushima, has recently been enjoying a renewed interest in his works. He passed away shortly after the end of the Second World War but his works are enjoying a second wave of growing interest perhaps driven by the renewed interest in translated works that recently swept the world. Actually, it was through fellow book bloggers that I first came across the Japanese writer who is considered one of the pioneers of the I-novel, one of the major literary movements that swept Japan. In 2023, I read my first novel by Dazai, No Longer Human, making The Setting Sun his second novel I read.

Originally published in 1947 as 斜陽 (Shayo), The Setting Sun is among Dazai’s most popular works and is often considered a classic of modern Japanese literature. The story was primarily narrated by twenty-nine-year-old Kazuko. She belongs to an impoverished aristocratic family living in post-war Tokyo. We join Kazuko as she reflects on her life and family, particularly on how they fell from grace. She had a younger brother Naoji whose whereabouts have been unknown. Kazuko, on the other hand, was divorced and returned to the family household, joining their mother. Kazuko claimed that she had an extramarital affair with a painter she admired. A wave of misfortunes forced the family to move to Izu in the countryside. Kazuko struggled with her feeling of inadequacy although she tried to adapt to life in the countryside, spending days working in the garden and taking care of her mother whose distress at being relegated to the countryside left her frail. However, the past kept disrupting the present. Memories of Kazuko’s childhood remained vivid. The crux of the story, however, was Kazuko’s affair with Mr. Uehara, a married novelist and an acquaintance of Naoji. Despite its slender appearance, the novel packed a punch. The story of Kazuko’s family’s decline echoes the decline of the aristocracy following the end of the Second World War. It is also the story of resilience and seizing one’s destiny. The Setting Sun is a riveting read from one of the masters of modern Japanese literature.

What will you read next?

Currently- Somewhere Beyond the Sea (Kindle books seem to take longer to read)

Finished- House in the Cerulean Sea

Next- Islands of the Blessed

LikeLike

I enjoyed We’ll Prescribe You A Cat

LikeLiked by 1 person