Family Ruptures

Without a doubt, Japanese literature is one of the most influential forms of literature in the world. Its contribution to world literature is incomparable. It boasts a legacy that spans centuries of history, having published one of the world’s earliest novels in Lady Murasaki Shikibu’s 源氏物語 (Genji monogatari; trans. The Tale of Genji. Shikibu’s legacy was preceded by top-caliber writers whose works have captivated the world. Her legacy is not left unnoticed as the works of Japanese literature transcend time. Over time, Japanese literature consolidated as one of the world’s most recognized and highly-regarded literatures. Its ascent to global recognition was further driven by globalization at the onset of the 20th century. Natsume Sōseki, Shiga Naoya, and Ryūnosuke Akutagawa have become household names. Their works have become hallmarks of Japanese literature; they are modern classics.

Beyond the wealth of literary works that emanated from Japan, Japanese literature’s extensive global reach can be attributed to how it constantly pushed the boundaries of literature. Haiku, a popular form of poetry, traces its provenance in Japan. Matsuo Bashō (1644–1694) is recognized as the greatest master of haiku. Among the several literary movements that shaped contemporary literature is the I-novel (私小説, Shishōsetsu, Watakushi Shōsetsu). The I-novel is semi-autobiographical in nature and dominated the Japanese literary scene in the early 20th century. It is prevalently a confessional form of literature but has evolved into an exposé of the author’s life and even society at large. Among the masters of the I-novel are Naoya Shiga, Osamu Dazai, and Nobel Laureate in Literature Kenzaburō Ōe.

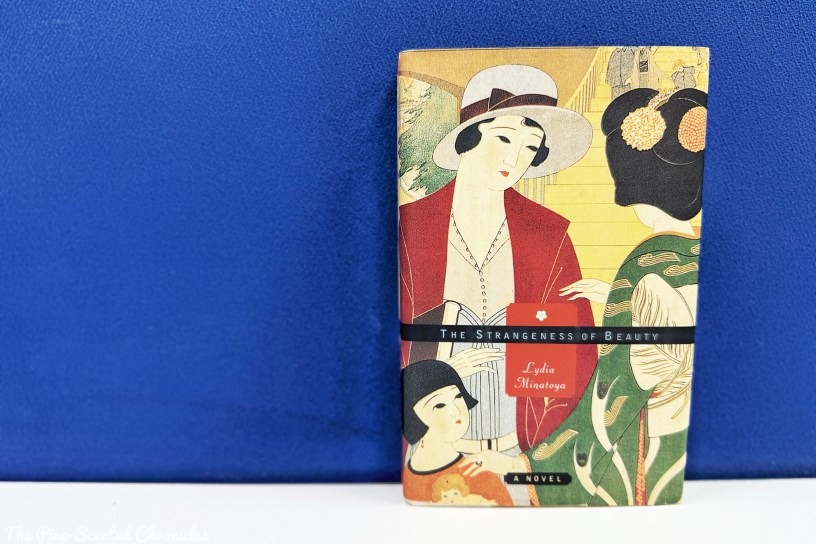

The I-novel has also been used to frame some works of modern Japanese literature. Take the case of Minae Mizumura’s A True Novel – the Japanese Wuthering Heights – which is a subtle probe into the integration of the I-novel with European literary influences. Another work of Japanese literature that fuses elements of the I-Novel is Lydia Minatoya’s first foray into full-length prose, The Strangeness of Beauty. Originally published in 1999, The Strangeness of Beauty takes on the form of a fictional autobiography – in the form of the novel’s heroine, Etsuko Sone. Her story started in 1918 when she, along with her husband Tadoa, decided to move from her birthplace of Kobe, Japan to Seattle, United States where they settled. Etsuko and her husband’s move was driven by the proverbial American dream.

There’s a reason why I tell this story. To me these Sunday painters represent myo – the strangeness of beauty – an idea that transcendence can be found in what’s common and small. Rather than wishing for singularity and celebrity and genius (and growing all gloomy in its absence), these painters recognize the ordinariness of their talents and remain undaunted.

Lydia Minatoya, The Strangeness of Beauty

Etsuko was looking forward to a city teeming with cultural activities in museums and libraries. She hoped that Seattle would embrace them and provide them with social mobility. However, reality was a far cry from her vision. She was soon disillusioned after merging from Seattle’s Immigration Building. Greeting her was a grim portrait of a city slowly descending into pandemonium, a far cry from her vision of the American Dream. Before her were eroding hills riddled with severed tree trunks, decomposing fish in the harbor, and mud. Tadoa, with his expertise in fabric and wood airplanes, dreamt of a career with Boeing. However, he had to settle with being a cook on an Alaskan fishing boat. He perished during a boating accident, leaving Etsuko widowed at a young age. However, she was not alone in an uncharted territory. Shortly after Etsuko and Tadoa moved to Seattle, they were joined by Etsuko’s sister Naomi and her husband Akira.

While Etsuko and Tadoa moved to Seattle in pursuit of the American dream, Naomi and Akira’s elopement was driven by their desire to move away from Etsuko and Naomi’s mother, Chie Fuji. Chie was not in favor of Naomi’s marriage. Unfortunately, tragedy would strike twice after Naomi died while giving birth to her daughter, Hanae. Etsuko took on the role of Hanae’s mother, raising and looking after her as if she was her own daughter. Hanae’s father, a dentist, on the other hand, slipped into a life of gambling. The crux of the story, however, was when Akira decided to have his daughter move back to Japan, particularly to the home of the Fujis. The goal was for Hanae to learn, rather re-learn Japanese tradition and culture in the house of her grandmother who descended from an aristocratic samurai family. Akira also believed that Japan would make Hanae come out of her shell.

Etsuko was reluctant with the plan but Akira successfully persuaded her to take Hanae with her to their family home. Etsuko herself never lived in the Fuji family home. When she was born, Etsuko was cast out by her mother who was still grieving from the recent loss of her young son; Etsuko was raised by silk farmers. While Hanae was reluctantly immersing herself in the Japanese way of life, her aunt was faced with the prospect of an uncomfortable reunion with her cold and distant mother. The story then follows how these three generations of Japanese women will navigate the sea of changes that were sweeping Japan in the years immediately preceding the war. As these events unfold and swirl, the three women are prompted to grapple with both the present and the past.

Chie, Etsuko, and Hanae were prompted to examine themselves and the complicated relationships they had with each other. Etsuko felt she belonged neither to the United States nor her native Japan. She slowly comes to terms with her past and present. She finally found purpose in raising her niece, with her eureka moment coming during Hanae’s preparation for her upper-school graduation. With nationalist sentiments swelling and Japan’s growing military expansion in the years preceding the War, Etsuko participates in antiwar activities. It was also at this juncture that Etsuko’s relationship with her mother started to show signs of improvement. A modest peace was achieved by their participation in various pacifist groups. Hanae, on the other hand, was working her way to the head of her graduating class of 1939.

And therein lies the transcendence. For as people pursue their plain, decent goals, as they whittle their crude flutes, paint their flat landscapes, make unexceptional love to their spouses – in their numbers across cultures and time, in their sheer tenacity as in the face of a random universe they perform their small acts of awareness and appreciation – there is a mysterious, strange beauty.

Lydia Minatoya, The Strangeness of Beauty

The Strangeness of Beauty is a multifaceted story that explores a plethora of subjects and themes. A multicultural story, one of the recurring themes in the novel is the stark dichotomy between Japanese and American cultures and ideals. The Asian diaspora, propelled by the pursuit of the proverbial American dream, was subtly underscored in the story. The American dream, brimming with rosy portraits and promises of greener pastures, fueled everyone’s imagination and desires. Reality, however, was a far cry from these glossy portraits, as Etsuko and Tadoa would eventually realize. This is one of the ironies of the American dream. Etsuko and Tadoa were immediately disillusioned by the grim realities they witnessed upon exiting Seattle’s Immigration Building. Despite the disappointment, they tried to make the American dream work in their favor.

While not autobiographical, the novel borrows inspiration from Minatoya’s own family. Minatoya and her parents were the first nonwhite – and the only Asian – family in the upstate New York town where she grew up. Further, Minatoya’s grandfather was a chef on an American freighter. Minatoya’s mother, like Etsuko, once worked as a bilingual designer in Daimaru, a Western-style department store. Minatoya’s family would be the subject of subtle displays of discrimination. In the novel, the growing anti-Japanese sentiment was another factor in prompting Akira to have his daughter move to Japan. The contrasts between Western and Oriental ideals weighed heavily on Etsuko. She felt she did not belong to either. Sailing in between two cultures, she wrestled with her identity as both American and Japanese. Etsuko’s impasse echoes the author’s own personal crisis.

Despite her reintegration into Japanese culture, Etsuko continues to question her identity. Etsuko’s experience reflects the sense of belongingness and alienation often felt by Japanese (Asians in general) Americans. They don’t belong in the Americas because their physical attributes distinguish them from the crowd. In Japan, they are also treated as strangers. Etsuko’s sense of abandonment was exacerbated by her own mother’s alienation of her as a young child; the complexities of families were extensively explored in the novel. The heart of the novel, after all, is the interplay of mother-daughter themes. Motherhood and sisterhood are both recurring themes in the novel. Like her aunt, Hanae was coming to terms with the abandonment of her mother. In the same breadth, the mothers (including surrogate mothers) struggled to understand the daughters who were truly not their own.

On top of the two overarching themes, loss and death were recurring themes in the story. Death cast a shadow on the lives of the characters, even shaping their individual destinies. For Chie and Etsuko, the death of a son caused her to create a distance between her and her children. Etsuko’s life, on the other hand, was largely influenced by the death of three people who were within her immediate circle: her brother, her sister, and her husband. The signs of the looming war riddled the story. The story was juxtaposed with the growing nationalist sentiment; interestingly, Chie was anti-imperialism. The nationalist sentiment ran parallel with the increasing militarization of Japan; this anchors the story on seminal historical events. The growing nationalism was contrasted by the antiwar sentiments in which Chie and Etsuko found a common ground. These historical contexts rendered the novel different layers.

And the reason is that he’s in training to be a writer. Observing detail, understanding irony, interpreting motivation. Hiro knows that acts are symbolic. The hard sour fruit offered too soon in its season carries a message. He has made an error in the timing of his visit. He has inconvenienced that family.

Lydia Minatoya, The Strangeness of Beauty

Taking on the form of a pseudo-diary, The Strangeness of Beauty lacks a robust and linear plotline. The novel instead provides intimate glimpses into the life of the novel’s main characters, although primarily through Etsuko. As a character, however, Etsuko was a cipher whose views and loyalties were often lacked depth and divided. While the novel was narrated primarily from Etsuko’s perspective, inconsistencies were noted in Etsuko’s narration of events she did not witness firsthand. Nevertheless, the novel found depth and texture in cultural touchstones. Lush details of Japanese culture riddled the landscape of the story. Sei Shonagon’s The Pillow Book, a seminal work of Japanese literature, was referred to. The novel is also a primer to samurai culture. However, the novel draws attention for its commentaries on a famed form of Japanese literature: the I-novel. Sections of the novel describe the challenges of writing autobiographical fiction.

“An idea that transcendence can be found in what’s common and small,” Etsuko describes the Japanese concept of myo from which the novel derives its title. Minatoya’s first foray into fiction, The Strangeness of Beauty is a lush tapestry that is riddled with several layers. It was a work of historical fiction that grapples with the sense of belongingness and alienation often felt by Japanese (Asian in general) Americans. Family dynamics were also extensively explored by Minatoya and details of Japanese culture made this facet of the novel all the more interesting. The novel is also a commentary on one of the famed forms of Japanese literature; the novel is a mock I-novel. These elements were supplemented by its meditations on family, culture, and life in general. A nominee for the National Book Award, The Strangeness of Beauty is an evocative story about war, clashing cultures, motherhood, and loss.

Book Specs

Author: Lydia Minatoya

Publisher: Simon & Schuster

Publishing Date: 1999

Number of Pages: 382

Genre: Literary, Historical

Synopsis

When Etsuko Sone’s sister dies in childbirth in Seattle’s shabby Japantown, love for the precocious child catapults Etsuko back across the Pacific and into the austere samurai household of her mysterious mother, Chie – a woman who rejected Etsuko at birth. The dubious reconciliation is for the sake of little Hanae, that she might learn her Fuji heritage and the Zen lessons of humility, dignity, self-discipline, and grace.

In Japan, Etsuko is the ultimate outsider: a returning emigrant in a land she left years before; a common woman thrust into a house of secrets and riches; a childless mother and a motherless daughter. As Etsuko and Hanae do their often quite comic best to adapt to life within Chie’s samurai household, Japan is changing in dangerous ways. Worldwide economic strife strips Japan’s people of food and clothing even as wartime preparations strip them of information and freedoms. Chie and Etsuko greet the mounting militarism with resistance, and when the imperial army cuts cruelly into Chinese Manchuria, accusations of treachery, of antipatriotism, begin to rain on the Fuji household. It is then that the women realize their separate independence is their common bond. It is then that Etsuko finds hidden strength to pursue meaning and beauty in a situation beyond her control.

Told with a social scientist’s feel for cultural, historical, and familial confusions and a poet’s ear and eye, The Strangeness of Beauty is a triumphant love story, a celebration of the capacity for transcendence that exists in every one of us.

About the Author

Lydia Yuri Minatoya was born on November 8, 1950, in Albany, New York, United States to Japanese immigrants. She attended Saint Lawrence University where she obtained a Bachelor of Arts. She earned a Master’s in Education from George Washington University in 1976 and a doctorate in counseling and psychology from the University of Maryland in 1981. Before publishing her works, Minatoya spent two years teaching at universities in Japan and China. She was also a faculty member at the North Seattle Community College.

In 1992, Minatoya published her first book, Talking to High Monks in the Snow: An Asian-American Odyssey, a memoir about her life as a Japanese American searching for cultural identity. The book was critically acclaimed, earning Minatoya the 1991 PEN/Jerard Fund Award. In 1999, she pivoted toward fiction with her first novel, The Strangeness of Beauty. The novel was nominated for the National Book Award and PEN Hemmingway Award. Minatoya’s written works also appeared in various publications and journals. Minatoya also received the Thomas M. Magoon Award for Distinguished Alumni from the University of Maryland.