Cats and Changes

While most modern societies and cultures revere dogs for their loyalty, contemporary Japanese society begs to deviate. In the landscape of modern Japanese pop culture, cats are ubiquitous and very popular. In a society that puts a premium on cuteness – kawaii culture – cats earn the edge. They are embedded in every layer of Japanese popular culture. Figurines like the maneki-neko (the beckoning cat) are found in shops and households. Popular anime and cartoon characters such as Hello Kitty and Doraemon are also cats. Cat cafés are also popular in Japan and there is even a Cat Island (Aoshima, Ehime) which is renowned for the large number of feline residents. Not only do the Japanese find them charming and cute, but they also find their sense of independence even more fascinating. On top of this, cats are often associated with positive symbolism; they are seen to usher in prosperity and good luck while warding off evil.

It comes as no surprise that the landscape of Japanese literature is brimming with the presence of felines. Japanese literature does not run out of works in which cats play prominent roles. There seemingly exists a symbiosis between these creatures and Japanese literature. The devout readers of works of Japanese literature have, at any point in time, encountered at least one of these works. One of the most recognized cat books is Natsume Sōseki’s I Am a Cat (吾輩は猫である, Wagahai wa Neko de Aru). Originally published in 1906, many a literary pundit considers the book a modern classic and a touchstone of contemporary Japanese literature. It also laid the groundwork for the advent of cat literature and the prevalence of cats in the vast ambit of Japanese literature. Following Sōseki’s classic, several cat books have since been released in the succeeding years.

The prevalence of cats in the ambit of Japanese literature has become more pronounced in the past three or four decades. Cats have become familiar presences in the works of Japanese literary heavyweight Haruki Murakami; like music and jazz, cats are recurring elements in his oeuvre. A cover of Kafka on the Shore features a cat. Hiro Arikawa also published two books featuring cats: 旅猫リポート (Tabi neko ripōto, 2012; trans., The Travelling Cat Chronicles, 2018) and みとりねこ (Mitori neko, 2021; trans., The Goodbye Cat, 2023). Other cat books translated into English include Sōsuke Natsukawa’s 本を守ろうとする猫の話 (Hon o mamorou to suru neko no hanashi, 2017; trans., The Cat Who Saved Books, 2021); Syou Ishida’s 猫を処方いたします (Neko o shohō itashimasu, 2023; trans., We’ll Prescribe You a Cat, 2024), and Genki Kawamura’s 世界から猫が消えたなら (Sekai kara neko ga kietanara, 2012; trans., If Cats Disappeared From the World, 2018).

Having played to her heart’s content, Chibi would come inside and rest for a while. When she began to sleep on the sofa – like a talisman curled gently in the shape of a comma and dug up from a prehistoric archaeological site – a deep sense of happiness arrived, as if the house itself had dreamed this scene

Takashi Hiraide, The Guest Cat

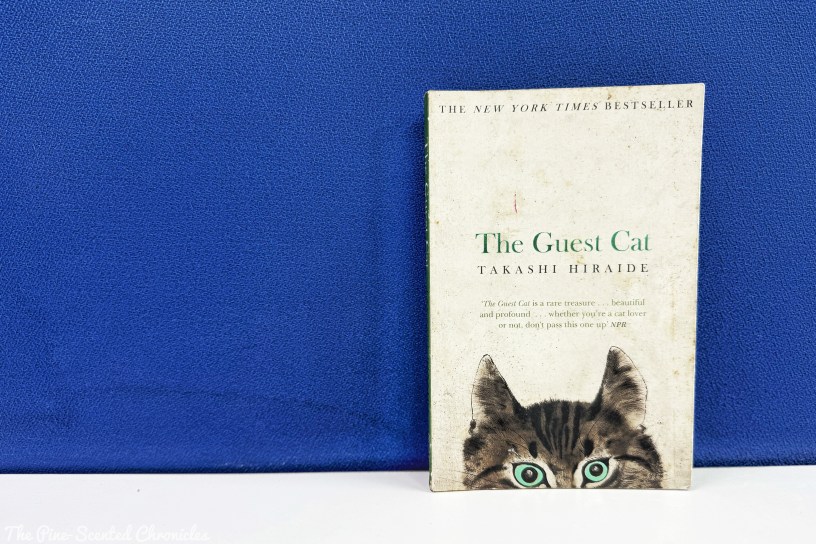

For sure, one would never run out of cat books in Japanese literature. Lending his voice and literary talent to this growing subgenre in Japanese literature is poet, literary critic, book designer, and professor Takashi Hiraide (平出 隆). While he has written several books of poetry and essay collections which have earned him various accolades in his native Japan, his most renowned work, at least to the Anglophone and global readers, is The Guest Cat; the book even landed on The New York Times bestseller list. Originally published in 2001 as 猫の客 (Neko no kyaku), it was eventually made available to English readers in 2014 with a translation by Eric Selland. The recipient of Japan’s prestigious Kiyama Shohei Literary Award in 2021, the deceptively slender book transports readers to late 1980s Japan.

At the heart of the story is a couple in their thirties who were renting a guesthouse on a large estate in one of suburban Tokyo’s more obscure sections; the vast property was owned and cared for by an old woman and her ailing husband. The couple are the typical Japanese in their thirties. They were devoted to their individual crafts. The husband in particular wanted to pursue a career as a full-time poet while his wife was a proofreader. Despite occupying the same space and their proximity, they barely speak to each other; they say little to each other beyond what is necessary. Their interactions are limited and they rarely leave their desks. The couple lived a detached and mundane existence. The natural harmony of their life was disrupted one day by the sudden appearance of a cat. The cat was a stray cat adopted by their neighbors across the street.

The couple was enamored by the beautiful young kitten which they started to call Chibi which roughly means small child in Japanese. They described Chibi as a “jewel of a cat. Her pure white fur was mottled with several lampblack blotches containing just a bit of light brown.” As the days go by, Chibi becomes a prevalent presence in the couple’s house. The cat visited them almost every day, spending as long as half the day just sleeping and eating the fried mackerel the author’s wife had prepared for her. She has started to insinuate herself into the couple’s life. She was even given her personal box made out of an old basket where she could rest. For the couple, Chibi was no mere distraction. She became the topic of their conversation. The titular Guest Cat, Chibi has symbolically become their surrogate child.

Despite not being their cat, Chibi has become an integral part of the couple’s life. Chibi brought charm and warmth into what was a mundane and uneventful existence. Once locked up in their work, the couple were willing to break their work whenever Chibi was around. The wife even kept a journal where she wrote details of what Chibi does during the day. They have come to love the unassuming creature that visits them every day. Their love flourished so much that their daily life revolved around Chibi. Nearly every major life decision moving forward also took Chibi into consideration. When the estate’s owner fell ill and eventually died, his wife decided to sell the property and move to an elderly home. The couple didn’t first think about themselves. Rather, their initial concern was finding a suitable home for Chibi.

I hesitated for a moment, then placed my hand on the old man’s naked body to help get him to his room. His skin was surprisingly soft and, considering how lean he was, still firm and healthy. There was no oiliness to it – he could almost have been a young school boy. With his eyes wide open, the old man chuckled, but seemed at a loss for words: he no longer had the willpower to move on his own. Then suddenly his body went limp and it was like carrying a dead weight.

Takashi Hiraide, The Guest Cat

On the surface, The Guest Cat explores the relationship between humans and animals. Pets, like babies, have been considered to usher a different warmth into a household. Their presence which some see as disruptive can alter the dynamics of relationships, as depicted in how Chibi became a catalyst in narrowing the chasm between the detached couple at the heart of the novel. It is also worth noting that neither husband nor wife was fond of cats. Nevertheless, Chibi presented a break from their routine. Not only did Chibi alter the couple’s dynamics but she was also integral in changing the landscape of their life. They always considered Chibi whenever they had to make an important decision. Before Chibi appeared in their life, the couple barely ventured out of the guesthouse they were occupying. From their sedentary lifestyle, the couple started to go out of their comfort zone more.

Along with Chibi, they started to explore the vast estate ground; they had no iota about how vast it was until they started going out. Too focused on their jobs, the couple barely noticed the lush garden and pond that surrounded them. They started to notice the plethora of plants and aquatic flowers that made the garden flourish. All the while, Chibi was climbing trees with ease while swatting insects. These small and playful acts fascinated the couple. Their relationship was tender and heartwarming. Chibi also provided them companionship and even tranquility. She also played a germane role in making the couple interact with their neighbors. The couple and Chibi forged a special relationship that the wife even compared their relationship to that of a fellow human: For me, Chibi is a friend with whom I share an understanding, and who just happens to have taken on the form of a cat.

The Guest Cat probes into genuine connections – albeit from a different and interesting perspective – and how this connection alters the landscape of one’s life. It is fascinating how Japanese literature uses cats as vessels to explore a plethora of subjects, from books to relationships to mortality. The cat at the heart of The Guest Cast ushers change and is symbolic. Chibi was the allegory of independence which the characters yearned for. To highlight the importance of Chibi, she was the only character provided with a name. All the other characters were simply referred to as the husband, the wife, a friend, or simply the old lady. The anonymity of the characters also renders the story a more profound and universal sense. However, the novel does not reduce itself to a mere story that explores the dynamics of human and animal relationships. The Guest Cat is a meditation about changes. The story was subtly juxtaposed to various changes, both on a personal and a societal level.

The story was juxtaposed in a period when Japan was dealing with surging prices of housing. The nation was also on the verge of economic insecurity and uncertainty. This historical event would eventually referred to as the Japanese asset price bubble. The novel is brimmed with subtly woven details of changes taking place. The garden was well-curated, with different flowers blooming at different times of the year, each highlighting the seasonal changes. The Kyoto-style garden was described as a collection of well-trimmed green hemispheres. The tadpoles eventually become froglets. The details of these changes were vividly captured by the descriptive nature of Hiraide’s writing. With the story spanning years, we also notice how friends and acquaintances grow old. Some even fell ill and eventually passed away. While the story underscores change, it also highlights impermanence. Even the house the couple was occupying was temporary.

Whenever someone walked by the narrow alleyway, a figure formed, filling the entire window. Viewed from the dark interior of the house, sunny days seemed ever more vivid, and working perhaps on the same principle as a camera obscura, the figures of people walking past were turned upside down. Not only that, but whatever images passed by came from the opposite direction than the one in which the people were actually walking. And as the passersby approached closer to the knothole, their overturned figures would swell so large that they would entirely fill the window frame and, once they had passed, would suddenly disappear like some special optical phenomenon.

Takashi Hiraide, The Guest Cat

For the husband, Chibi’s presence was even more critical. Just when Chibi appeared in their lives, tectonic plates were shifting. He recently quit his publishing job and became a freelance writer; writing was his passion. Major life decisions were at hand. Perhaps more importantly, the author was forced to reckon with his own mortality: Looking back on it now, I’d say one’s thirties are a cruel age. At this point, I think of them as a time I whiled away unaware of the tide that can suddenly pull you out, beyond the shallows, into the sea of hardship, and even death. The characters reckoned with aging and the inevitability of death; these are further manifestations of change and impermanence. On top of this, he was anxious about managing expenses and the old couple who owned the estate. Chibi was his reprieve. Chibi was a break from the monotony of his and his wife’s lives.

Overall, The Guest Cat is an introspective novel that is, on the surface, seemingly whimsical and playful. It reels the readers in as it moves forward. Chibi, cute and unassuming, independent and tender, was a vessel to explore complex subjects and even emotions. She was the crucible of change for the couple. From their monotonous life, the couple’s dynamics and life were altered by Chibi, quite unexpectedly considering how they were not fond of cats. Their unexpected relationship slowly evolved into a heartwarming story that is also a philosophical rumination on change, impermanence, the passage of time, and the indelible connections between humans and animals. The beauty of nature was also vividly captured by Hiraide. The Guest Cat captures the pleasures found in simple things and even in fleeting relationships. It is deceptively slender but it resonates with warmth that ultimately explores love and loss.

There are a few cat lovers among my close friends, and I have to admit that there have been moments when that look of excessive sweet affection oozing from around their eyes has left me feeling absolutely disgusted. Having devoted themselves to cats, body and soul, they seem at times utterly indifferent to shame.

Takashi Hiraide, The Guest Cat

Book Specs

Author: Takashi Hiraide

Translator (from Japanese): Eric Selland

Publisher: Picador

Publishing Date: 2014 (September 2001)

Number of Pages: 136

Genre: Historical, Literary

Synopsis

A couple in their thirties live in a small rented cottage in a quiet part of Tokyo. They work at home as freelance writers. They no longer have very much to say to one another.

One day a cat invites itself into their small kitchen. She is a beautiful creature. She leaves, but the next day comes again, and then again and again. New, small joys accompany the cat; the days have more light and colour. Life suddenly seems to have more promise for the husband and wife; they go walking together, talk and share stories of the cat and its little ways, a play in the nearby garden. But then something happens that will change everything again.

About the Author

Takashi Hiraide (平出 隆, Hiraide Takashi) was born on November 21, 1950, in Moji, now a part of Kitakyūshū, Fukuoka. He graduated from Hitotsubashi University in the 1970s. Post-university, he worked as an editor at Kawadeshobishinsha, a publishing house in Tokyo.

While working at the publishing house, he published his first collection of poems, The Inn, in 1976. The book was warmly received and established Hiraide as one of the leading poets in post-war Japan. His second book of poems, For the Fighting Spirit of the Walnut (1982), earned him the Education Minister’s Art Encouragement Prize for Freshman. His third poetry collection, Portraits of a Young Osteopath, was published in 1984. Shortly after its publication, Hiraide spent three months at the University of Iowa as a poet in residence for the International Writing Program.

Hiraide’s succeeding works transcend the borders of literary genres. Notes for My Left-hand Diary (1993) won the Yomiuri Literary Award and was a fusion of poetry and essay. Postcards to Donald Evans (2001) was a poetic book of letters addressed to a dead artist. His most globally recognized work, however, was The Guest Cat (2001). The book is the winner of Kiyama Shohei Literary Award. On top of this, Hiraide also published several books of essays on art, travel, and even sports. He also published a travelogue, The Berliner Moments, in 2002 which detailed his experiences as a visiting scholar at the Berlin Free University. It earned him The Travel Writing Award.

Apart from writing, Hiraide also taught at Tama Art University as a professor of Poetics and Art Science. He was also a core member of the new Institute for Art Anthropology. Hiraide is married to poet Michiyo Kawano