And with that, the year’s first quarter has concluded. How time flies. A lot has happened but, at the same time, it doesn’t feel like anything happened at all. There are also times when it feels like yesterday when we welcomed 2025 with quite a fanfare. Anyway, how has the year been so far? I hope that it is going your way. If the year is going awry, I hope you will have a reversal of fortune in the coming months. Moreover, we have the rest of the year to pursue our passions, embark on new journeys, and achieve our goals. I hope before the year ends, everyone has healed and received heaps of positive news and energy. I hope everyone’s prayers have been answered. However, if your goal this year is to make it from one point to another, it is still okay. With the turmoil that envelops us, muting the noise can be quite a challenge. For those who have set their goals, I hope you get to accomplish them all. More importantly, I hope everyone stays healthy, in mind, body, and spirit.

Speaking of goals, I have quite several lofty ones in terms of reading. For one, I already set my target to 100 books. I usually set a conservative target at the start of the year and recalibrate it as the year goes on. However, as the past three years have shown, I can definitely cross the three-digit mark. One of my goals this year is also to read more translated books than books originally written in English. As part of this agenda, I commenced my 2025 reading year with the works of East Asian writers; this was also driven by my inability to hold a Japanese literature month in the past year, the first time I failed to do so in years. As such, the first quarter of the year was dedicated to the works of East Asian writers. I finally concluded this wonderful journey in March, albeit with a special twist. Since March is Women’s History Month and March 8 is International Women’s Day, March was dedicated to the works of female East Asian writers. This is my way of tipping my hat toward them and recognizing their contributions to the world of literature.

So before I move on to the next month of the year, let me share the conclusion of my foray into works of East Asian literature. Happy reading!

Honeybees and Distant Thunder by Riku Onda

My journey across East Asian literature continued with an unfamiliar name, at least to me, but from a literary territory that has become a comfort zone. Recently, a remarkable number of Japanese literary works have been made available to Anglophone readers. Among them is Riku Onda’s Honeybees and Distant Thunder which I first encountered through an online bookseller. My interest was piqued, prompting me to include the book in my 2025 Top 25 Reading List, making it just the fourth book from the list I read. Originally published in 2016 as 蜜蜂と遠雷 (Mitsubachi to enrai), Honeybees and Distant Thunder is the third novel by Onda to be translated into English. The novel is centered around the Yoshigae International Piano Competition, a fictional contest set in a rural seaside town. Due to its prestige, the competition attracted some of the world’s young piano prodigies and even some veteran musicians. The story, however, focuses on the stories of four characters: sixteen-year-old Jin Kazama, a relatively unknown prodigy and the son of a beekeeper; Aya Eiden, a former child prodigy who took a hiatus from the concert scene after getting burned out; Masaru Carlos Levi Anatole who is an equally renowned pianist who was even dubbed as The Prince of Juilliard; and Akashi Takashima who, in his twenties, is among the older entrants but his dream of making it into the music scene so that his son would eventually be proud of him for what he achieved as a musician drove him. Onda takes the readers through each round of competition as more competitors are eliminated. Tension and drama converge with light and tender moments as new relationships flourish. Honeybees and Distant Thunder is also a riveting read about the beauty of music. It is a substitute for language and a means to capture the beauty that words cannot seem to describe.

Goodreads Rating:

Scattered All Over the Earth by Yōko Tawada

From an unfamiliar name to a familiar one. It was during the lead-up to the announcement of the 2018/2019 Nobel Laureates in Literature that I first encountered Yōko Tawada. A couple of years later, I am reading my third novel by the highly-heralded Japanese writer; interestingly, she has moved and taken residence in Germany and is even writing in German. Scattered All Over the Earth was technically a random purchase but a promising one. Originally published in 2018 as 地球にちりばめられて (Chikyū ni chiribame rarete), a work of dystopian fiction, very much like the first two Tawada novels I read. The story commences in the Danish capital where Knut, a linguistics student, finds himself captivated by a woman – Hiruko – he saw while randomly scrolling through TV shows. Born in a country that no longer exists, Hiruko wants to find other native speakers of her language so that she can speak it again. She speaks Panska, a homemade language that combines Scandinavian languages. Knut contacted the station and connected with Hiruko and together they embarked on a journey to find another person speaking the language of her homeland. The story alternates between the perspectives of different characters such as Akash, Nora, and Tenzo. Scattered All Over the Earth is a depiction of Japan slowly disappearing although the story starts in medias res. The details of what happened before, however, are left to the reader’s imagination. Nevertheless, Scattered All Over the Earth tackles the disintegration of language but it is also a microcosm of a world descending into chaos due to discord and the inability to understand each other. While Japan was never directly mentioned, details of Japanese pop culture – such as sushi – remind the readers of this. Overall, Scattered All Over the Earth is an interesting take on an interesting subject.

Goodreads Rating:

Twenty Fragments of a Ravenous Youth by Xiaolu Guo

From Japan – well, technically, from Europe -my literary journey next took me to mainland China. Unfortunately, my foray into the works of Chinese writers has been quite limited. In fact, I have not read any works by female Chinese writers originally written in Chinese. This puts Xiaolu Guo’s Twenty Fragments of a Ravenous Youth in a very unique spot. While it is the first novel by Guo I read, it is the sixth novel written by a Chinese writer I read this year. Twenty Fragments of a Ravenous Youth was originally published in 2000 as 芬芳的37.2度 and charted the fortunes of Fenfang, a young female film extra living in Beijing. When she was seventeen, Fenfang left her parents in the countryside where they ran a potato farm with no desire to return. In the bustling Chinese capital, she wanted to start a new life; this new life is the focus of the novel which was conveyed in vignettes, hence the twenty fragments referred to in the title. The pursuit for success in the bustling capital, however, proved to be a long and winding journey, especially as Fenfang was navigating uncharted territories. Success was elusive. Opportunities with substantial pecuniary gains came once in a blue moon if they even come at all. The failures, however, did not dampen Fenfang’s spirit. What makes the novel more interesting is the details of communist Beijing. Fenfang lived in the Chinese Rose Garden Estate, one of several Beijing estates constructed to replace the traditional hutongs. The estates seemed new but were crumbling inside. Fenfang also tried earning diplomas and certifications which she kept in her Mao drawer. At one point, Fenfang had to report to the police station under the suspicion of being a perpetrator of a crime. Twenty Fragments of a Ravenous Youth is a quick read but nevertheless an engaging coming-of-age story in communist China.

Goodreads Rating:

Marigold Mind Laundry by Jungeun Yun

My literary journey next took me to the Korean Peninsula where the literary scene is gaining some attention in the global scene, particularly after Han Kang became the first Korean writer to win the International Booker Prize with her novel The Vegetarian. It opened the doors for Korean writers as more of their works were translated, with some even nominated for prestigious literary prizes. One of the recently translated Korean works that has become ubiquitous is Jungeun Yun’s The Marigold Mind Laundry. Marigold Mind Laundry was originally published in 2023 as 메리골드 마음 세탁소. On the surface, it seems to have been fleshed from the same template as Hwang Bo-Reum’s Welcome to the Hyunam-Dong Bookshop and Yeon Somin’s The Healing Season of Pottery. After all, the three books deal with healing in a tumultuous world. What sets Marigold Mind Laundry apart is its integration of magical realist elements. In a fictional village referred to as a village of wondrous powers, Jieun, the novel’s main character, was born with the power to heal and make wishes come true. At a young age, she got separated from her parents, prompting her to travel across time to search for them. It proved to be an improbable task as she found herself trapped in a cycle of rebirth and despair, She eventually settled in an idyllic seaside village where she conjured up a hilltop laundromat. It was no ordinary laundromat as it could remove stains of the heart. The rest of the story then follows Jieun as she deals with different individuals who seek healing. Their stories highlight several modern concerns such as the follies of social media, society’s absurd beauty standards, and gender expectations. However, Yun fails to live up to the expectation. The overall impact was fleeting as Yun is more fixated on the idea of sharing more stories rather than exploring these subjects deeper.

Goodreads Rating:

Moshi Moshi by Banana Yoshimoto

Japanese literature, without a doubt, is riddled with several prominent female writers although they are not as renowned as their male counterparts, at least with the works made available to Anglophone readers. Among the prominent names is Banana Yoshimoto who made waves with her debut novel, Kitchen; it was the first book by the Japanese writer I read and it was a pleasure reading it. This made me seek more of her works and a couple of years later, I read my third novel by Yoshimoto, Moshi Moshi. In a way, this is a conscious effort to balance the gender scale. Moshi Moshi, originally published in 2012 as もしもし下北沢 (Moshi moshi Shimokitazawa, started on a bleak note. The catalyst for the story was the death of Yoshie’s father; Yoshie was the novel’s main character and primary narrator. Yoshie’s father was a talented but minor musician who committed suicide with his younger lover who was also his cousin. The titular Moshi Moshi refers to the phone that Yoshie’s father left at home before he went to commit the deed. His suicide came as a shock to his wife and daughter who were oblivious to the life he led as a musician. As Yoshie and her mother reflected on his absences, details were not adding up, adding salt to the injury. This prompted Yoshie to ruminate on her relationship with her father. To move on from her grief and her father’s act of betrayal, Yoshie moved out of their condo and started working in a bistro called Les Liens. Questions about her father’s life lingered, making Yoshie start digging into her father’s past. The novel, however, pans into Yoshie’s romantic life while, at the same, it captures the essence of a place, particularly the neighborhood of Shimokitazawa. In bustling Tokyo, the neighborhood is an oasis of calm. Moshi Moshi, like Kitchen, grapples with grief but it is also about rebuilding one’s life and finding new joy from this grief.

Goodreads Rating:

Mild Vertigo by Mieko Kanai

Like in the case of Tawada, it was through the lead-up to the announcement of the 2023 Nobel Prize in Literature awardee that I first came across Mieko Kanai (金井 美恵子). I did come across her through online booksellers because her works are republished by Fitzcarraldo, an independent publisher that has recently been producing Nobel Laureates in Literature like Olga Tokarczuk and Jon Fosse. Kanai’s name was tossed among the list of leading candidates. Despite not getting the award, my interest in her was piqued, hence, the inclusion of Mild Vertigo to my 2025 Top 25 Reading List. Originally serialized in Katei gahō, the book was eventually published as a collective in 1997 as 軽いめまい (Karui memai). At the heart of the novel is Natsumi. She is a housewife living in modern Tokyo with her husband and their two sons. The novel is divided into vignettes; this is a literary tool that I find ubiquitous in the landscape of contemporary Japanese literature. Essentially a slice-of-life story, each chapter paints a vivid portrait of the intricacies of domestic life. Details of Natsumi’s life were captured by Kanai. We see Natsumi performing her role as a wife and mother, from making dinner to washing dishes to even eating out with friends and gossiping with neighbors. On the surface, these all sound mundane. However, each chapter, alternating between internal monologues and interactions with her family, provides profound insights about life that reeled me in. Apart from the philosophical undertones, the novel paints a vivid portrait of Natsumi’s community and how it affects her life. The book is a rather slender one but it brims with warmth and tenderness stemming from Natsumi’s ruminations about her life and the people around her. These are reflections that make Mild Vertigo a relatable and compelling story.

Goodreads Rating:

Can’t I Go Instead by Lee Geum-Yi

I have been going to and fro Japan and Korea. With the astronomic rise of KPop and KDrama in recent years, it was just a matter of time before Korean literature would seize the global stage. And sure, Korean literature did take the global stage which can chiefly be attributed to Han Kang. More and more Korean titles were also made available to Anglophone readers. Among these writers is Lee Geum-Yi who has a prolific career as a children’s story writer. Can’t I Go Instead is the first book by the Korean writer I read. Can’t I Go Instead commences on April 29, 1920, when Lady Gwak, the mistress of the Gahoe-dong mansion in Japanese Empire-ruled Seoul went into labor. Viscount Yun Byeongjun, her father-in-law, recently passed away under scandalous circumstances and left his son, Hyeongman, to occupy the position he once led. Lady Gwak and her husband’s relationship, however, was on the rocks. After several failed births, Lady Gwak finally gave birth to a daughter the Viscount named Chaeryeong, one-half of the two girls/women at the heart of the novel. When Chaeryeong’ turned eight, her father brought her to a countryside village to retrieve her present, a maidservant. Another girl was bought to be her maidservant but seven-year-old Sunam stepped up and presented herself, “Can’t I go instead?”. Sunam was the other half that formed the novel’s backbone. On the backdrop, the story covers germane historical events that shaped the contemporary Korean landscape and how these events altered the two characters’ lives. Can’t I Go Instead navigates war and the intricacies of growing amid a turbulent and violent time rife with changing tides. What illuminates, however, are the resilience and unwavering spirit of the two women amid a world continually shifting. Overall, Can’t I Go Instead is a riveting read.

Goodreads Rating:

Cocoon by Zhang Yueran

From one work of historical fiction to another. As mentioned, I have rarely read works of female Chinese writers and to read two in a month is quite a progress. Ironically, despite its vast influence, Chinese literature, overall, remains largely unexplored by me. The second female Chinese writer I read in 2025 is Zhang Yueran whose novel Cocoon I first encountered during one of my random ventures into the bookstore. Curious about what it has in store, I obtained a copy of the book and made it part of my ongoing venture into East Asian literature. Originally published in 2016 as 茧, Cocoon commences with the reunion of two childhood friends: Li Jiaqi and Cheng Gong. Now in their twenties, they have lost connection and have been incommunicado for nearly two decades. This was after Li Jiaqi was called back to the family home in Jinan to look after her dying grandfather. Her grandfather was an iron-willed patriarch who, during his heyday, was the most famous heart surgeon in China. In alternating fashion, they flash back to the past and relate their own stories. Meanwhile, Gong’s grandfather lies in a vegetative state in Room 317 of the local hospital after an unknown assailant drove a nail into his skull during the Cultural Revolution. The shadow of the Cultural Revolution looms above the story as both Jiaqi and Gong were raised by dysfunctional families whose lives were altered by the Revolution. Personally, I rarely encountered this germane historical event in the books I read. Apparently, the Cultural Revolution birthed its own literature referred to as scar literature. Cocoon, however, focuses on the impact of the Cultural Revolution on the generation immediately succeeding it. Yueran herself is a part of this generation so, in a way, the novel was a personal one. Overall, Cocoon is a vivid portrayal of a seminal historical event and its legacy.

Goodreads Rating:

The River Ki by Sawako Ariyoshi

That’s three works of historical fiction in a row that took me from South Korea to China and finally, to Japan. Without a doubt, Japanese literature has become a home for me and one of my favorite literatures. It has not, however, escaped my attention how sparse the Japanese female voice is, particularly in the 20th century, at least in works that have been translated into English. The names one would associate with 20th-century Japanese literature are primarily men. Nevertheless, some female writers rose to prominence. Among those who made a mark was Sawako Ariyoshi whose novel, The River Ki, was ubiquitous; it would be the second novel by Ariyoshi I read. Originally published in 1959 in serialized form in the magazine Fujin Gahō, it was eventually published as a complete book carrying the title 紀ノ川 (Kinokawa). The novel commences at the turn of the 20th century and introduces the beautiful Hana Kimoto and her grandmother, Toyono. The first pair of three female characters at the core of the novel, we first met them as they were visiting a temple in Wakayama before twenty-year-old Hana’s wedding. Following her parent’s untimely demise, Hana was raised by her grandmother who allowed her to study at Wakayama Girls School. Her grandmother also taught her traditions. While there was a move toward modernity, traditions eventually prevailed as Hana was set to marry Keisaku Matani. The succeeding chapters captured two more sets of mother-daughter relationships: Hana and her daughter Fumio and Fumio and her daughter Hanako. Through their stories, Ariyoshi captures how Japan is slowly moving toward modernization, including progressive ideals about feminity. However, these are stymied by tradition. The River Ki is an ode to the passage of time and the slow disintegration of traditions. It is for these facets that I find The River Ki an engaging read.

Goodreads Rating:

Woman Running in the Mountains by Yūko Tsushima

For my next read, I stayed in Japan. Speaking of female Japanese writers, another prominent female Japanese writer is Yūko Tsushima who was born Satoko Tsushima. She was the daughter of famed novelist Osamu Dazai (born Shūji Tsushima). Despite her provenance, she stepped out of the shadows of her famous father and built an equally impressive literary career that earned her many of Japan’s top literary prizes, including the Izumi Kyōka Prize for Literature, the Noma Literary New Face Prize, the Noma Literary Prize, the Yomiuri Prize, and the Tanizaki Prize. Among Tsushima’s renowned works is Woman Running in the Mountains. Originally published in 1980 as 山を走る女 (Yama o hashiru onna), the novel charts the fortune of Takiko Odaka in 1970s Japan. When the novel commences, she is making her way to the hospital as she is due to give birth. The crux is that Takiko is twenty-one years old and unmarried. Her situation was exacerbated by the fact that the baby was the result of an affair with a married man who never made an appearance in the story. With Japanese society frowning on cases like hers, Takiko’s parents were against her pregnancy. These, however, did not stop her from pushing through with the pregnancy. The birth goes smoothly but things started to unravel shortly after she and her son were discharged from the hospital. Takiko, however, was determined to be a good mother. More importantly, she did not let her motherhood and the obstacles she had to endure redefine her. Takiko was very much her own. She worked hard for a decent job and a life away from her neighborhood’s prying eyes, vicious parents, and the threat of destitution. Woman Running in the Mountains vividly captures the experience of being a single mother in Japan albeit during a different time, hence, different prevailing attitudes which could potentially shock some readers.

Goodreads Rating:

Untold Night and Day by Bae Suah

From Japan, I crossed the Korean Strait once again for a venture into Korean literature, perhaps the last this year. As I have mentioned, several Korean writers have become household names following Han Kang’s International Booker Prize breakthrough. Another writer who was introduced to the global stage is Bae Suah who made her literary debut in 1993 with A Dark Room. Over the course of her career, she published short stories and novels, elevating her to being one of South Korea’s more renowned contemporary authors. Among her works is Untold Night and Day. Originally published in 2013 as 알려지지 않은 밤과 하루 (Allyeojiji Anh-Eun Bamgwa Halu), the novel charts the fortunes of twenty-eight-year-old Kim Ayami. She used to attend law school but dropped out to pursue a career in acting. Apparently, she is not a good actress as well, prompting her to take a job at a theater library for the blind in Seoul after juggling waitressing jobs. However, the theater was about to shut its doors permanently which means Ayami is on the brink of unemployment yet again. Fortunately, her German teacher, Yeoni, brought a work opportunity. A German writer was about to arrive in Seoul. The writer required an assistant, prompting Ayami to set off to meet him at the airport. A second character, Buha, soon enters the scene. Buha is a former businessman who roamed the streets looking for a woman whose picture he saw in the newspaper years ago. When his path crosses with Ayami’s, he confronts her because he wants to confirm if she is the woman he has been looking for. But this is just the surface. Bae takes the readers on an unusual ride which can be quite disconcerting particularly if one is seeking a linear story. For a book seemingly slender, it is brimming with images and repetitions. Untold Night and Day was certainly an experience.

Goodreads Rating:

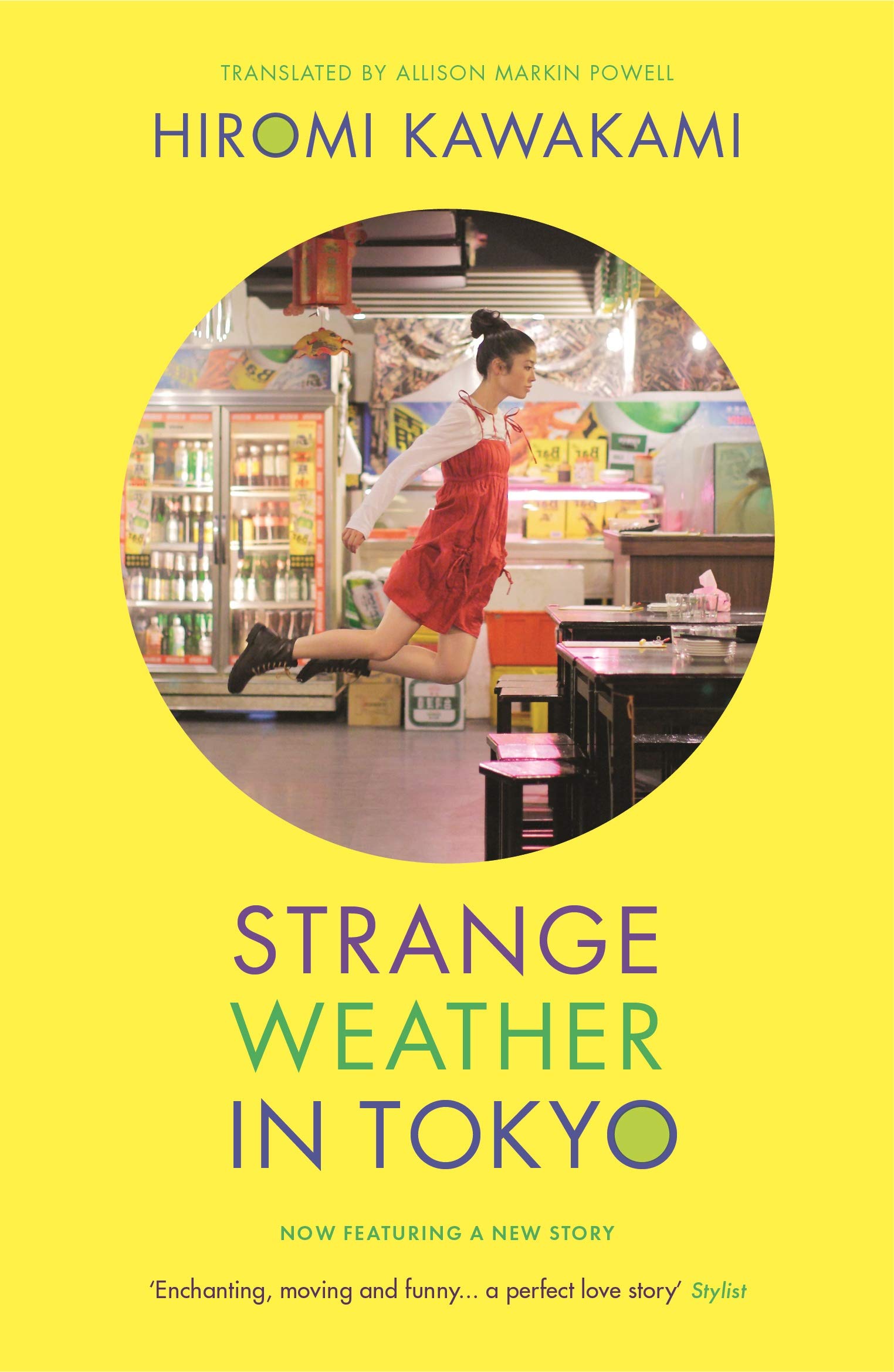

Strange Weather in Tokyo by Hiromi Kawakami

To conclude my March reading journey, and, in the process, effectively closing my foray into East Asian literature, I traveled from South Korea to Japan, once again crossing the Korean Strait. To conclude one-quarter of East Asian literature, I returned to a familiar name in Hiromi Kawakami with her novel Strange Weather in Tokyo. Last year, I read Under the Eye of the Big Bird which was just announced as part of the International Booker Prize shortlist. From what I understand, Strange Weather in Tokyo was the book that elevated Kawakami to global recognition. Originally published in 2001 as センセイの鞄 (Sensei no kaban), the novel won the 37th Tanizaki Prize and was originally translated into English as The Briefcase. It was later republished as Strange Weather in Tokyo. The novel charts the fortunes of thirty-seven-year-old Tsukiko Omachi, a woman living alone in Tokyo, spending her free time alone in her apartment, reading books, bathing, and talking to herself. The flow of her life was disrupted by a serendipitous encounter with an individual from her past. At a local bar near Tokyo Station called Satoru’s, Tsukiko ran into sixty-seven-year-old Harutsuna Matsumoto. Matsumoto had been observing Tsukiko for some time before finally approaching her to confirm if she was Tsukiko Omachi. Tsukiko soon realizes that Matsumoto is her high school teacher. Over the following months, more encounters, mainly unarranged, brought the two together. They bonded and soon forged a friendship built around their encounters at the bar. They were rebuilding and rekindling their connection through their memories and shared interests. They were full of contrasts but despite this, their friendship flourished. Strange Weather in Tokyo is a bittersweet story of friendship, the passage of time, and, ultimately, parting.

Goodreads Rating:

Reading Challenge Recaps

- 2025 Top 25 Reading List: 6/25

- 2025 Beat The Backlist: 4/20; 34/60

- 2025 Books I Look Forward To List: 0/10

- Goodreads 2025 Reading Challenge: 34/100

- 1,001 Books You Must Read Before You Die: 1/20

- New Books Challenge: 0/15

- Translated Literature: 32/50

Book Reviews Published in March

- Book Review # 574: When the Emperor Was Divine

- Book Review # 575: We Do Not Part

- Book Review # 576: The Guest Cat

Like in February, I was looking forward to bouncing back in March after very busy and sluggish months. I tried to complete as many book reviews as I could but I was unable to do so because March was, unexpectedly, a very busy month. I had to finish yet another document, much like in January. I actually just finished the document and my body is still recovering from the mental and physical exhaustion I experienced. To think that my body and mind have not yet recovered from the hectic month that is January. Further, balancing work with personal life is quite a challenge. Despite this, I was able to publish three book reviews, a far cry from my target of ten. But hey, I can only look at the brighter side. Even though three is a meager number, I am glad that I was finally able to finish all my pending book reviews from April 2023. Although I have yet to publish a book review this April, I am looking forward to completing all my pending reviews from May 2023 although the goal is still to take it one step at a time. Nevertheless, I will try to complete as many book reviews as I can.

Reading-wise, in April I have pivoted toward the rest of the Asian continent to explore the literary scene of the world’s largest continent. I have already commenced this journey with two works of Turkish writers, Elif Shafak and Orhan Pamuk. I am also currently reading a work by a Filipino writer, one that was originally written in Tagalog. On top of this, I have lined up some works of Indian writers like Salman Rushdie’s debut novel, Grimus; and still some works of East Asian writers that are part of my ongoing reading challenges. I am also going through my heaps of books to find other titles to immerse myself in. Hopefully, I get to find some although the ones that I am currently looking at are mainly works of Filipino and Indian writers.

How about you fellow reader? How is your own reading journey going? I hope you enjoyed the books you have read. For now, have a great day. As always, do keep safe, and happy reading everyone!