The Road to Literary Greatness

It cannot be denied that Chinese literature is one of the most storied and extensive literatures in the world. With a rich and long history that spanned millennia- the earliest archeological records show that Chinese literature already existed as far back as the 1700 BC – it is easily one of the world’s most prominent and influential literatures. It boasts some of the most important and studied literary works. The most prominent of which are collectively referred to as the Four Great Classical Novels of Chinese literature: Luo Guanzhong’s Romance of the Three Kingdoms (三國演義, Sānguó Yǎnyì), Shi Nai’an’s Water Margin (水滸傳, Shuǐhǔ Zhuàn), Wu Cheng’en Journey to the West (西遊記, Xī Yóu Jì), and Cao Xueqin Dream of the Red Chamber (紅樓夢, Hónglóu Mèng) or The Story of the Stone (石頭記, Shitou Ji). A modern variation cited two more novels – Lanling Xiaoxiao Sheng’s The Plum in the Golden Vase or The Golden Lotus (金瓶梅, Jīn Píng Méi) and Wu Jingzi’s The Scholars (儒林外史, Rúlín Wàishǐ).

These are works that have transcended time and even physical boundaries. They are among the most important tomes of classic Chinese literature if not world literature as a whole. With its vast expanse, Chinese literature spans a wide copse under which different forms of literature and genres thrive; on top of the classics are works of poetry, prose, historical texts, and drama, among others. Incorporated into these works are elements of philosophy, drama, and even the visual arts. Its legacy well extends beyond the physical boundaries of China because Chinese literature also influenced the literary traditions of its neighboring countries. Further, it holds the distinction of having literature that was written in a single language; there were variations but they were few and rare in between. These are just the tips of the iceberg as influences of Chinese literature are intricately woven into the finer points of world literature.

With such a long and rich heritage, it can be daunting to follow up from there. Nevertheless, a bevy of contemporary Chinese writers have stepped up and taken on the challenge of furthering the causes of Chinese literature, ensuring its continued relevance. Among them is Guan Moye (管谟业) who goes by his more popular pseudonym Mo Yan (莫言). Born to a farming family in China’s Shandong Province, his literary talent manifested when he enlisted in the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) in 1976. He began writing in 1981 using the pseudonym Go Yan which literally translates to “don’t speak.” He pursued his study of literature at the PLA Academy of Art from 1984 through 1986 where he continued writing stories. He boasts an extensive oeuvre that spans short stories, novels, and essays. For his rich body of work, he was awarded the 2012 Nobel Prize in Literature, making him just the second Chinese writer to earn the distinction.

Over decades that seem but a moment in time, lines of scarlet figures shuttled among the sorghum stalks to weave a vast human tapestry. They killed, they looted, and they defended their country in a valiant, stirring ballet that makes us unfilial descendants who now occupy the land pale by comparison. Surrounded by progress, I feel a nagging sense of our species’ regression.

Mo Yan, Red Sorghum

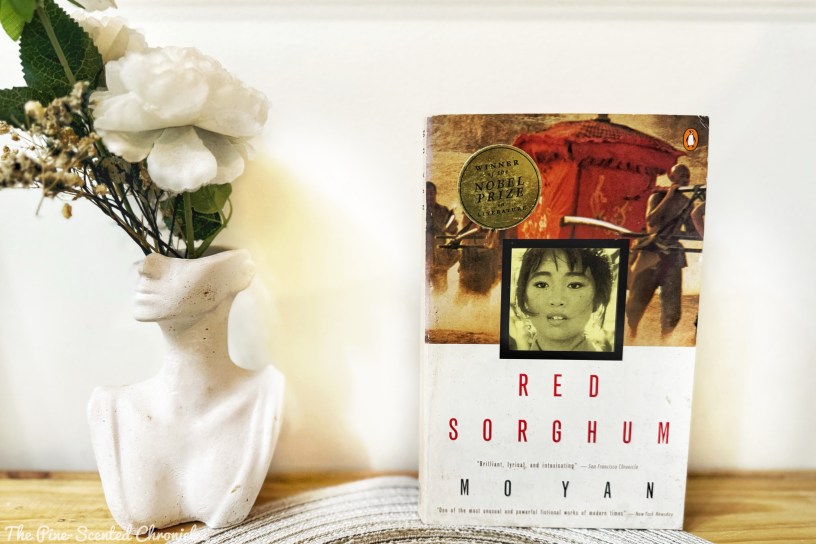

In Mo Yan’s extensive literary vitae, one work easily stands out. Among his works cited by the Swedish Academy was his debut novel, Red Sorghum. It was initially published serially in various magazines in 1986 before it was collectively published as a single volume in 1987 with the title 红高粱家族 (Hóng Gāoliáng Jiāzú). The book earned Mo Yan widespread fame and was germane in catapulting him to global recognition. Red Sorghum is comprised of five novellas: Red Sorghum, Sorghum Wine, “Dog Ways, Sorghum Funeral, and Strange Death. It chronicled the story of three generations of the Shandong family from the 1920s to the 1970s. Serving as the novel’s spiritual guide across this landscape is an unnamed son of the fourth generation; he is the grandson of Commander Yu. The family’s story is set primarily in Northeast Gaomi Township which was inspired by Dalan Township, Gaomi County in Shandong, the author’s hometown.

The family’s story started in 1923 with Dai Fenglian, the narrator’s grandmother; she was familiarly referred to by the narrator as Grandma and Little Nine by her father before she got married. As tradition had it, the sixteen-year-old was arranged to be married to Shan Bianlang, the son of Shan Tingxiu, the richest man in the village. However, like most arranged marriages, Little Nine has not met her groom but she heard grim things about him, particularly that he was a leper. Aboard a sedan on the way to the Shan household for the marriage ceremony, Grandma was held up by a bandit. One of the sedan carriers, Yu Zhan’ao, managed to stake a claim on the bandit when the bandit was distracted. The convoy was able to make it through to the Shans and the union pushed through against Grandma’s fears. Post-ceremony, as tradition dictates, Grandma had to return to her village for three days.

While Little Nine was spending her final days with her family, disaster struck. In her absence, her husband and father-in-law were murdered. No one knew who the perpetrator was but it nevertheless left Little Nine a widow. Grandma was not an unhappy one as she was bequeathed a fortune, particularly her father-in-law’s successful sorghum wine–making business and distillery. Armed with an indomitable spirit, Grandma was undeterred by the death of her husband. She took charge of her destiny and capably took charge of the wine distillery. In taking charge of the business, she was assisted by one of the Shans’ loyal foremen, Uncle Arhat Liu, who would also play a germane role in the life of the Shans. One day, Yu walks in looking for work and is granted it. It was eventually revealed that Grandma was pregnant with the narrator’s father, Douguan. However, these are details that are revealed as the story moves forward.

One of the facets that distinguishes Red Sorghum is its nonchronological timeline. This nonlinear storytelling can be seen as either a challenging or interesting facet of the story. The story oscillates between different periods. When the novel starts, it is already 1939, on the battlefield where Grandfather, garbed in his battle regalia, is preparing the local army for the looming invasion of the Japanese army; on the battlefield, Grandfather is referred to as Commander Yu. China was on the brink of the Second Sino-Japanese War. Commander Yu who brought along with him his teenage son, was preparing for an ambush on a Japanese truck convoy. Commander Yu and his army preparing for the ambush is one of the two prominent plotlines in the novel; the other plotline captures the story of the narrator’s grandparents.

They crouched and watched the dog path where Mother was pointing. The sorghum stalks, pelted by sheets of glistening raindrops, were trembling. Everywhere you looked there were tightly woven clumps of delicate yellow shoots and seedlings that had sprouted out of season. The air reeked with the odor of young seedlings, rotting sorghum, decaying corpses, and dogshit. The world facing Father and the others were filled with terror, filth, and evil.

Mo Yan, Red Sorghum

In a nutshell, Red Sorghum is a family saga. The unnamed narrator, with his unflinching gaze, painted the history of the Shandongs as they shifted from being sorghum winemakers to resistance soldiers during the Second Shino-Japanese War. Like most families, they have trials and tribulations, all of which are captured in the novel. Their story is also riddled with secrets and betrayals. Horrific events have also defined their story. Adding color to the novel are the members of the family who, individually, give the story interesting textures. They are complex characters who have despicable characteristics but also have redeeming qualities. They had flaws but it is their flaws that make them interesting and compelling characters. Commander Yu, for instance, is a sympathetic character. However, he can also be a cruel and violent tyrant. He has no qualms about resorting to violence to obtain what he wants. Grandma’s beauty belies a fierce and determined woman.

This strike of balance is also palpable in the other characters and their own destiny. The love shared by Grandfather and Grandma is contrasted by the turmoil of the time. Beauty is constantly contrasted by suffering; the story is brimming with violence. Bloodshed, death, and disputes between gangs and political rivals were prevalent. These were juxtaposed with the sorghum fields of the Chinese countryside; sorghum is the primary root crop of the area. It is from these fields that the Shandong family earned its fortune but it is also underneath these fields that their bodies and those who perished during the turmoil were buried. It can be surmised that the ripe redness of the sorghum field was from the blood that had watered and cultivated it. The sorghum then is a metaphor.

The destiny of the Shandong family is entangled with war, hence, the bloodshed; the story is riddled with historical contexts. Graphic details abound throughout the story but it is also these intense imageries that amplify the messages woven astutely into the novel’s lush tapestry. The looming Second Sino-Japanese War, which would eventually develop and snowball into the Pacific War, initially set the novel into motion. The Japanese invaders perpetrated atrocious acts. At the start of the novel, Uncle Arhat is flogged and then skinned alive by the Japanese. The Japanese forced the men of the village to work on a highway they started to build while the women were locked in a brothel to serve Japanese soldiers. In response to this, the villagers created groups to resist against the invaders. Commander Yu and his son play central roles in the resistance. Again, the Shandong winery would once again play a germane role as it was a refuge for the fighters. What was once a symbol of abundance has become a metaphor for resistance.

But the narrator’s dive into the past is more than a concerted effort to chronicle his family’s history. With the past eventually merging with the present, the narrator is figuring out how to make sense of these events that haunted his family: Then a deolate sound comes from the heart of the land. It is both familiar and strange, like my granddad’s voice, yet also like my father’s voice, and like Uncle Arhat’s voice, and like the resonant singing voices of Grandma, Second Grandma, and Third Grandma, the woman Liu. The ghosts of my family are sending me a message to point the way out of this labyrinth. It is his effort to make sense of how his family’s history translates into the present. This contributes to the detached quality of storytelling as memory can be muddled and distorted. Nevertheless, he is the product of his father’s heroic deeds and his grandmother’s resilience. Their stories were critical in his understanding of himself.

A heavy bracelet of twisted silver slid down to her wrist, and as she looked at the coiled-snake design her thoughts grew chaotic and disoriented. A warm wind rustled the emerald-green stalks of sorghum lining the narrow dirt path. Doves coooed in the fields. The delicate powder of petals floated above silvery new ears of waving sorghum. The curtain, embroidered on the inside with a dragon and a phoenix, had faded after years of use, and there was a large stain in the middle.

Mo Yan, Red Sorghum

As the story progresses, clarity develops. The Shandong family and the village are a microcosm of Chinese society. The Shandongs are the epitome of Chinese families of their time. Their story provides a window into the traditions and social order of their time. Even before the arrival of the Japanese, life in the village was both terrible and magical. As tradition subtly reverberates in the story, various facets and details of Chinese culture are depicted, especially at the start of the novel when Little Nine is arranged for marriage against her wishes. As tradition dictates, she was carried to the house of her husband-to-be in a sedan; Yu Zhan’ao was among the sedan carriers. There is a lot to unpack in the story as myth and superstition are woven into the lush narrative. Rabid dogs abounded the story. This is deliberate as they are symbols for greedy warlords who lorded over the countryside.

Despite the horrors that permeate the story, what eventually emerges is the resilience of the characters and of the Chinese people. They were undaunted by the war. Rather than balking against the challenge, they displayed indomitable courage to survive the odds. And this spirit is displayed not just on the battlefield. In the winery, the workers and the women were resourceful in the face of suffering. All the while, time passes and change is inevitable. When the narrator returns to his homeland to visit the grave of his grandparents, he notices that the red sorghum of his Grandma’s time has slowly been replaced by different variants of sorghum. These new variants have choked the red sorghum. This perfectly encapsulates his family’s story. Meanwhile, the book refers to the Cultural Revolution.

All of these wonderful elements were woven into a lush tapestry by Mo Yan’s dexterous hands. The interesting characters melded with the lush historical contexts. The vividness of the story was further enriched by the integration of magical realist elements. Mo Yan’s brand of magical realism is reminiscent of Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s brand of magical realism. Nevertheless, Mo Yan crafted his own brand of magical realism anchored on the epics and myths that have defined Chinese literature and culture. Allegories and motifs aldo riddled the story, providing it even more distinct textures. The biggest allegory, of course, was the titular red sorghum. It was a symbol of life and sustenance, not only for the Shandong family but also for the village.

Red Sorghum is a rich and multilayered novel. On the surface, it is the story of the Shandong family, from their days of being successful winemakers to their transformation as heroes and leaders during the Second Sino-Japanese War. They displayed courage and indomitable spirits in light of unimaginable adversities that pervade their life and the Chinese countryside. More importantly, the novel is a testament to the Chinese spirit, and, by extension, the human spirit. It is the story of courage and resilience. The novel is also a window into China’s contemporary history while underscoring the horrors of war. Nevertheless, Red Sorghum, a family saga, a coming-of-age novel, and a historical novel, is a testament to the enduring human spirit in the face of great misery and suffering. Red Sorghum is a brilliantly crafted novel that announced the emergence of a powerful literary voice.

Over decades that seem but a moment in time, lines of scarlet figures shuttled among the sorghum stalks to weave a vast human tapestry. They killed, they looted, and they defended their country in a valiant, stirring ballet that makes us unfilial descendants who now occupy the land pale by comparison.

Mo Yan, Red Sorghum

Book Specs

Author: Mò Yán (莫言, born Guan Moye 管谟业)

Translator (from Chinese): Howard Goldblatt

Publisher: Penguin Books

Publishing Date: 1993

Number of Pages: 359

Genre: Historical, Magical Realism

Synopsis

Spanning three generations, this novel of family and myth is told through a series of flashbacks that depict events of staggering horror set against a landscape of gemlike beauty, as the Chinese battle both Japanese invaders and each other in the turbulent 1930s.

A legend in China, where it won major literary awards and inspired an Oscar-nominated film, Red Sorghum is a book in which fable and history collide to produce fiction that is entirely new – and unforgettable.

About the Author

Guan Moye (simplified Chinese: 管谟业; traditional Chinese: 管謨業) was born on March 5, 1955, in Ping’an Village, Gaomi Township, Shandong, China. He was the youngest of four children born to a farming family. Guan attended primary school in his hometown but his education was disrupted by the Cultural Revolution, prompting him to drop out in fifth grade. He then participated in farm work for years before he started to work at the cotton oil processing factory in 1973. Following the conclusion of the Cultural Revolution in 1976, he enlisted in the People’s Liberation Army (PLA). It was during his time in the army that he became interested in writing. In 1991, he graduated from the joint master’s program in literature at the Lu Xun School of Literature and Beijing Normal University.

In 1981, Guan began writing stories under the pseudonym Mo Yan (莫言), which literally translates to Don’t Speak. It would be under his pseudonym that Mo would become renowned. While studying literature at the PLA Academy of Art from 1984 through 1986, he published stories such as Touming de hongluobo (Transparent Red Radish) and Baozha (Explosions; Eng. trans. in Explosions and Other Stories). In 1987, Mo Yan published his first novel, 红高粱家族 (Honggaoliang jiazu, Red Sorghum). It earned Mo Yan widespread recognition and the book was even adapted into film. His subsequent works include 天堂蒜薹之歌 Tiantang suantai zhi ge, 1989; The Garlic Ballads), 酒国 ( Jiuguo, 1992; The Republic of Wine), 丰乳肥臀 (Fengru feitun, 1995; Big Breasts and Wide Hips), and 生死疲劳 (Shengsi pilao, 2006; Life and Death Are Wearing Me Out).

Mo Yan has also published short stories and short story collections, and, essays and essay collections, and even wrote plays, plays, including Women de Jing Ke (Our Jing Ke) and Bawang bieji (Farewell My Concubine), both published in 2012. For his works, Mo Yan earned various accolades from across the world including the 2006 Grand Prize of the Fukuoka Asian Culture Prizes in Japan and the 2005 International Nonino Prize in Italy. In 2009, he was the first recipient of the University of Oklahoma’s Newman Prize for Chinese Literature. In 2012, Mo was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature for his work as a writer “who with hallucinatory realism merges folk tales, history and the contemporary”. This makes him the first Chinese citizen to win the Nobel.