Happy Wednesday, everyone! Wednesdays also mean WWW Wednesday updates. WWW Wednesday is a bookish meme hosted originally by SAM@TAKING ON A WORLD OF WORDS.

The mechanics for WWW Wednesday are quite simple: you just have to answer three questions:

- What are you currently reading?

- What have you finished reading?

- What will you read next?

What are you currently reading?

It is already the middle of the week. How has your week been? I hope it’s going well and going in your desired direction. Woah. Time is indeed flying fast! We are in the second half of the month. Oh my. Before we know it, we will already be halfway through the year, which also means that I am about to become a year older. Anyway, how has the year been so far? I hope it’s going well for everybody. I hope you are being showered with blessings and good news. I hope the rest of the year will be prosperous, brimming with wealth, but more importantly, good physical and mental health. I hope everyone is already making progress on their goals. If the year is going otherwise, I hope you will experience a reversal of fortune in the following months. In terms of reading, I am already halfway through my goal of reading 100 books. In fact, I am way ahead of my target. Should I hold this reading momentum, 2025 will be the fourth consecutive year I read at least 100 books.

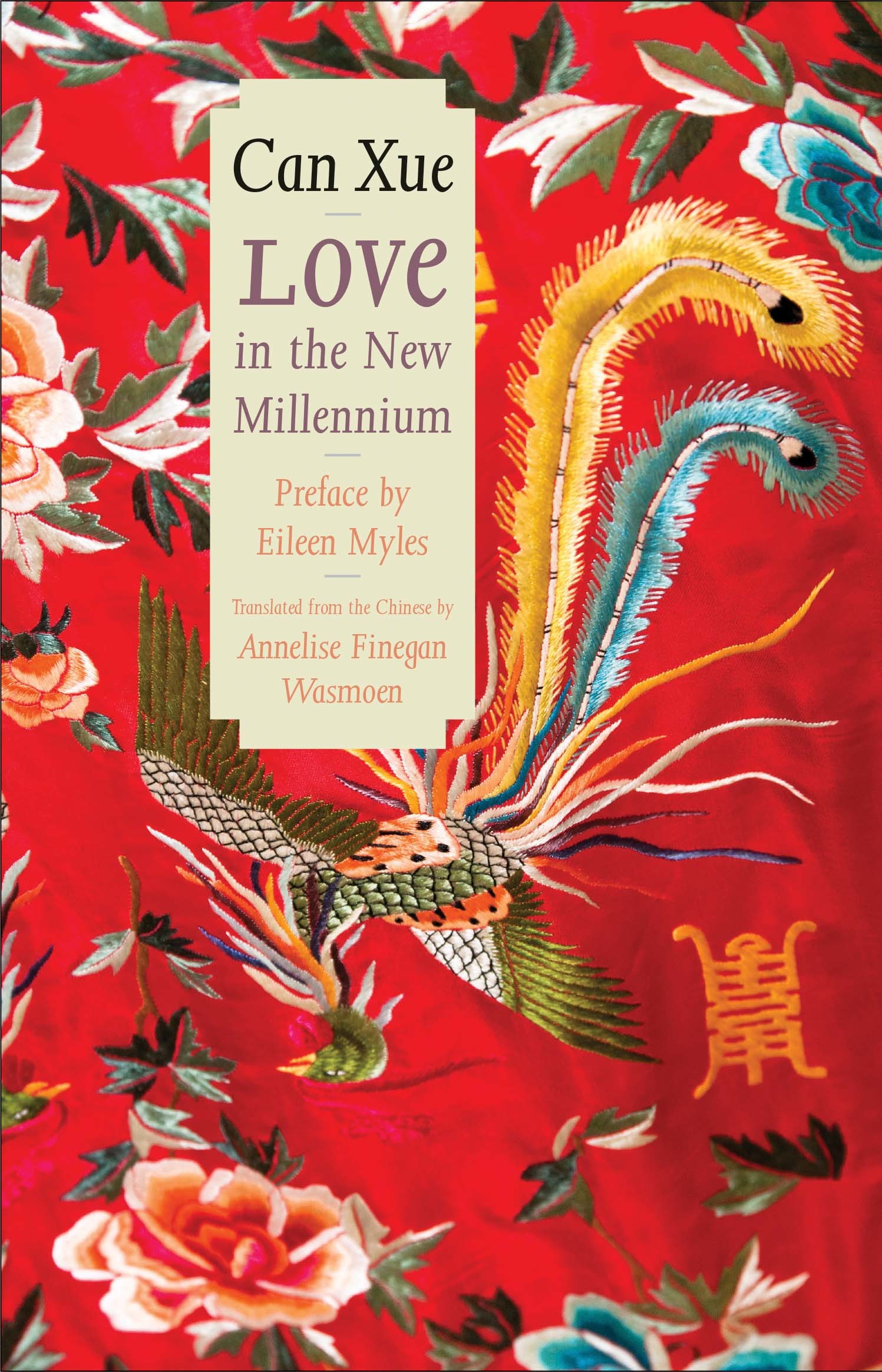

Currently, I am reading works of Asian writers after spending the first quarter of the year reading works of East Asian writers. Essentially, the half of the year is mainly works of Asian writers. This takes me to my current read, Can Xue’s Love in the New Millennium. I first encountered the Chinese writer through online booksellers, although I overlooked her. A couple of years later, I would encounter her once again, now as a possible awardee of the Nobel Prize in Literature. She has been topping betting sites for two years in a row, although she walks away without the highly coveted distinction. Nevertheless, it was more than enough to pique my interest and give her oeuvre a chance. Love in the New Millennium serves as my primer to the avant-garde writer born Deng Xiaohua. By the way, Can Xue, dubbed as one of the most prominent contemporary Chinese writers, was also awarded the Neustadt International Prize for Literature.

Longlisted for the International Booker Prize, Love in the New Millennium introduces a vast cast of characters who were mainly connected to China’s underground sex industry. It comes as no surprise that most characters were also sex-driven. The catalyst for the novel’s main action is Wei Bo’s breakup with his lover, Cuilan. Suddenly appearing on her door one day, Wei Bo told her he couldn’t keep their date. He has since failed to return to her, prompting Cuilan to go back to her ancestral home in the countryside. Things in the countryside were not making sense either. I guess this scene lays out the landscape of the story. As the story moved forward, it became increasingly becoming more abstract. A robust plot it has not, although the characters grapple with similar themes. For instance, Long Sixiang, Jin Zhu, and A Si were middle-aged women who once worked at a cotton mill. In the present, they were all sex workers. Strange? Kind of. But I guess this is stemming from the fact that this is my first time reading Can Xue’s works. Nevertheless, I am looking forward to how she will steer the story forward, or at least how I can make sense of it.

What have you finished reading?

The past week was a rather slow reading week, at least in terms of reading output. I managed to complete just two books, and one the week prior. This is mainly because of the first of two books I completed in the previous week. When I acquired a copy of Eiji Yoshikawa’s The Heike Story earlier this year, I was not planning on reading it immediately; I guess it was bound to suffer the same fate as my other books. However, when I noted that I was approaching my 1,300th novel, I ran a catalogue of the books I own to check which one deserves to occupy this important milestone. My initial choice was Umberto Eco’s Foucault’s Pendulum, which is part of my 2025 Top 25 Reading List. In the end, I chose The Heike Story because it is aligned with my current reading motif.

At the heart of The Heike Story is the titular Heike clan, a warrior clan that thrived in twelfth-century Kyōtō, which, back then, was the Imperial capital. This was a tumultuous period in Japanese history. With Emperor after Emperor either abdicating or being deposed, Japanese society was on the cusp of pandemonium. The deposed Emperors further instigated chaos by plotting schemes to overthrow the current Emperor/s. Japanese society was mired in political and social instability. Effectively, two houses were the loci of political affairs. The first, obviously, is the Imperial Palace, while the other was the Cloistered Palace, which housed the abdicated Emperors. Over the years, the Imperial Palace was losing its influence and control, leaving the Cloistered Palace the de facto source of power. The situation was exacerbated by the lack of trust among the courtiers,s who all wanted to seize control. As the courtiers battled it out in the imperial court, the warrior clans were left to suffer the consequences.

Among the prominent warrior clans is the Heike clan, headed by Heita Kiyomori, who was also the central force of the novel. He was the son of Tadamori, a once-trusted Imperial palace official and the leader of the Heike clan before it started losing influence, and Yasuko, the Lady of Gion and former lover of an abdicated Emperor. Kiyomori’s provenance was one of intrigue, but this did not hamper him from rebuilding the lost glory of the Heike clan. From being a lowly warrior, he slowly gained a reputation not only as a warrior but also as a wise leader. He slowly catapulted his clan to greater glory. In the process, he interacted with the Imperial court officials and Emperors. The Heike Story, to say the least, is very eventful, with layers of romance, betrayal, forgiveness, and violence permeating it. And apparently, the novel is the modern prose rendering of a classic Japanese epic.

It is actually quite the experience. The details of warrior and clan life, juxtaposed with the lack of political will of the emperors, provide glimpses of the Japan of old. It can get quite graphic as details of violence and even decapitation were woven into the novel’s lush tapestry. These, however, do not dim the novel’s luster. It is an epic and a compelling historical account. Now I am hoping I get to read The Tale of Genji. Ironically, the Heike clan went head-to-head against the Genji clan.

From Japan, I traveled back, in terms of literature, of course, to my country for another dose of Philippine literature. Like in the case of The Heike Story, I had no book in mind. But with the Philippine Independence Day celebrated on the day I finished The Heike Story, it was but logical to read a work of a Filipino writer. This led me to Azucena Grajo Uranza’s Bamboo in the Wind. Before last year, I had not heard of Grajo Uranza, nor had I encountered any of her works. I guess the same can be said of most of the writers whose bodies of work I have been exploring. Anyway, a random encounter with the book during a random escapade at the local bookstore led me to this interesting title.

Bamboo in the Wood transports the readers to the year immediately preceding the Martial Law (Presidential Decree Number 1081), one of the most germane events in contemporary Philippine history. At the heart of the story are three families whose lives have converged in the fictional town of Laguardia. In the story’s present, Larry Esteva (Lorenzo Esteva Jr.) returned home to the Philippines after studying abroad. At the airport, Larry witnesses a violent dispersal of demonstrators by the Philippine Constabulary. It barely touched him as Larry is part of Manila’s alta de sociedad; he is of the elite class. His father, Don Lorenzo (one of the three patriarchs) was a haciendero in Laguardia. His father was friends with the father of Arsenio de Chavez, the second of the three patriarchs. While studying at Francis Xavier University, they met Celestino Limzon, who, unlike them, was born to a family of more modest means.

The three boys from Laguardia would eventually rise above their ranks. Don Esteva was a wealthy landowner. Arsenio de Chavez became a senator and a close ally of the sitting president. Limzon, on the other hand, became a judge. But the 1970s – the story’s setting – was a time of social and political upheaval. The children of the three Laguardian natives have increasingly become involved in the country’s political activist movements. In particular, Connie de Chavez and Ramon Limzon, having witnessed firsthand the oppression of the urban poor and the farm peasants, have become involved in the quest for social equity and justice. However, this runs parallel with the growing insurgency. Radicalism has instigated radical measures that threaten the stability of the country. This resulted in the declaration of the Martial Law. Bamboo in the Wind is a harrowing portrait of this important section of contemporary Philippine history. It vividly captures scenes that have become ubiquitous in documentaries. I guess this is where I felt the book fell short. The story became predictable, although there are affectionate moments as the characters experience the oppression of the Martial Law firsthand. Overall, it was a good and insightful read.

What will you read next?