The Complexities of Human Nature

In the vast literary landscape, German literature stands proud as one of the most prominent and influential traditions. With a rich heritage that spans centuries, its contributions to the growth and development of world literature cannot be underestimated. Key literary movements such as the Enlightenment and Romanticism trace their roots and evolution to German thought. German philosophers like Immanuel Kant were central figures in the former, while the latter first took root in Germany before spreading to influence literary trends across Europe and beyond. In fact, the very concept of world literature originates from German letters—Johann Wolfgang von Goethe coined the term Weltliteratur to describe the cross-border exchange of literary ideas. These factors have elevated German literature to the upper echelons of global literary excellence.

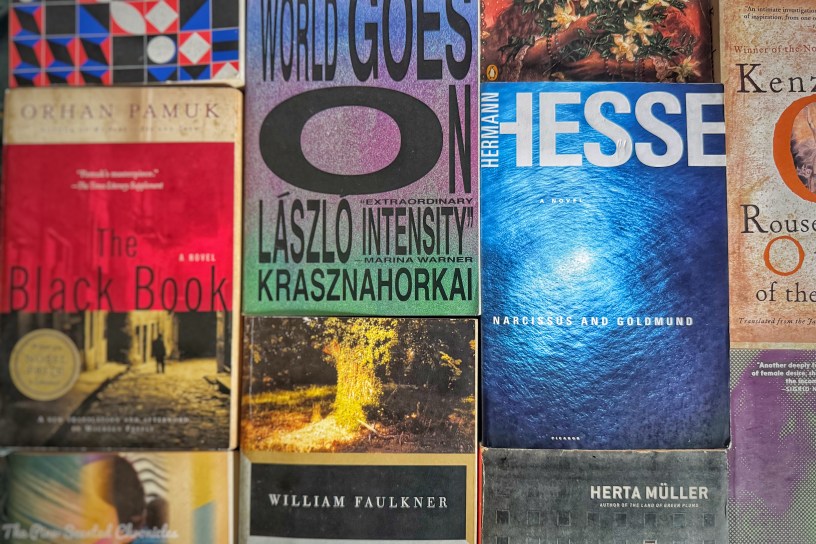

Further underscoring its influence is Germany’s long tradition of producing stellar storytellers. These writers have created some of the most renowned works in world literature, which remain integral to contemporary literary discourse. Their oeuvres have earned them accolades and recognition worldwide. The Swedish Academy has even honored several of them with the Nobel Prize in Literature, often considered the highest achievement for any writer. Notably, German historian Christian Matthias Theodor Mommsen was the second-ever Nobel laureate in Literature, earning the award in 1902 for being “the greatest living master of the art of historical writing, with special reference to his monumental work A History of Rome.” He was the first of ten German writers to receive the Nobel Prize, the most recent being Herta Müller in 2009.

Following in Mommsen’s footsteps was Hermann Karl Hesse. Born on July 2, 1877, in Calw, Germany, the young Hesse aspired to be a poet, sharing his mother’s passion for poetry and music. Before pursuing a full literary career, he worked in bookstores in Tübingen and Basel. In 1896, he took his first step into literature with a poetry collection, and in 1904, he ventured into prose with his debut novel Peter Camenzind, a success that allowed him to support himself as a writer. Over his career, he published a wide range of works—novels, novellas, poetry, short stories, and nonfiction. The diversity and depth of his oeuvre earned him the Swedish Academy’s recognition. In 1946, Hesse received the Nobel Prize in Literature “for his inspired writings which, while growing in boldness and penetration, exemplify the classical humanitarian ideals and high qualities of style.”

Art was a union of the father and mother worlds, of mind and blood. It might start in utter sensuality and lead to total abstraction; then again it might originate in pure concept and end in bleeding flesh. Any work of art that was truly sublime, not just a good juggler’s trick; that was filled with the eternal secret, like the master’s madonna; every obviously genuine work of art had this dangerous, smiling double face, was male-female, a merging of instinct and pure spirituality.

Hermann Hesse, Narcissus and Goldmund

Although Hesse began his career as a poet, he became best known for his novels, among which Narcissus and Goldmund stands out. Originally published in 1930 as Narziss und Goldmund, the novel is set in medieval Germany. It opens with the young Goldmund entering Mariabroon, a monastery in the countryside. Eighteen-year-old Goldmund—whose name literally translates as “Gold Mouth”—was brought there by his father to atone, through asceticism and devotion, for the sins of his decadent and unruly mother. Determined to make amends for her unspecified transgressions, Goldmund immerses himself in monastic life and the study of arts and sciences. Extroverted and imaginative, he is a dreamy, sensitive, and individualistic student fascinated by the world’s beauty and mystery.

Goldmund’s outgoing spirit draws the attention of Narcissus, a brilliant, ascetic, and disciplined young monk—the youngest teacher in the monastery. Despite his youth, Narcissus has already established a reputation for intellect and spiritual rigor. In Goldmund, he recognizes his antithesis. Though they are polar opposites, they become close friends. Narcissus—embodying intellect and order—serves as both mentor and challenger to Goldmund. Their friendship, while deep, is not without tension. Through insightful observation, Narcissus realizes that Goldmund’s monastic calling stems not from his own desire but from his father’s will. He seeks to awaken Goldmund’s true nature while maintaining restraint to avoid suspicion of favoritism.

Encouraged by Narcissus, Goldmund begins to recall long-buried memories of his mother and grows increasingly curious about the world beyond the cloister. His awakening is sparked by a chance encounter with a village girl who kisses him—an act that ignites within him a longing he can no longer ignore. It was a eureka moment for the young man who realized that he was not cut out for life in the monastery. Abandoning his dream of becoming a monk, Goldmund embarks on a journey that exposes him to breadth of human experience: sensuality, art, suffering, and the fleeting beauty of life. He embraces unpredictability and freedom. He was carefree, choosing to live in the moment rather than overthink. While embracing the uncertainties, Goldmund let life unfold.

In his journeys, Goldmund encountered a wide array of characters. He also discovered and indulged in the beauty of sensual love; women were constantly throwing themselves at him because of his beauty. Among these women were the daughters of a Count with whom he worked for as a scholar; it was one of several occupations he took on while he ventured across the outside world. Despite their good relationship, Goldmund soon fell out of the Count’s good graces after the Count learned that Goldmund seduced his two daughters; Goldmund did develop feelings for Lydia, the older of the two sisters. After being kicked out of the castle, Goldmund resumed his meandering. More sexual encounters would ensue. His carnal experiences were wrapped in joy, exuberance, and even suffering.

He thought the fear of death was perhaps the root of all art, perhaps also of all things of the mind. We fear death, we shudder at life’s instability, we grieve to see the flowers wilt again and again, and the leaves fall, and in our hearts we know that we, too, as transitory and will soon disappear. When artists create pictures and thinkers search for laws and formulate thoughts, it is in order to salvage something from the great dance of death, to make something that lasts longer than we do.

Hermann Hesse, Narcissus and Goldmund

When Narcissus unlocked his long-kept memories, Goldmund resolved to emulate his mother who was a romantic who lived a life brimming with adventure. Goldmund’s adventure was, in a way, a quest to find the archetypal figure of the nurturing mother. But as Goldmund scours the world outside the monastery, he comes up to several profound realizations, underscoring the complexities of human nature. An early encounter with a cunning drifter named Viktor prompted Goldmund to contemplate mortality and the fleeting nature of existence. This unexpected encounter on the road was further prompted Goldmund to ponder on the nature mortality. He wonders if the fear of mortality is a catalyst in fueling artistic creation. He noted how artists and creatives alike strive to leave a legacy that would transcend both time and boundaries.

Goldmund’s encounter with Viktor proved to be pivotal in his journey. Upon entering a church to confess, he is mesmerized by a sculpture of the Virgin Mary—an experience that awakens his artistic calling. Under the tutelage of Master Niklaus, a renowned woodcarver, Goldmund discovers his gift for sculpture. Through art, Goldmund created artistic renditions of the human form. He channels his life experiences, encompassing both the sad and the joyful. Goldmund thrived as an artist. More importantly and ambitiously, through his art, Goldmund aspired to craft a universal portrayal of motherhood. Motherhood is a recurring theme; interestingly, when Hesse worked on the manuscript, he intended to use “the quest for motherhood” as a subtitle, but ultimately rejected this urge.

As the story progresses, motherhood takes on more profound shapes. In Goldmund’s pursuit for maternal love, he found a connection to eternal mother through art, love, and even his sensual experiences. Even death assumes a motherly aspect for him. Goldmund embodies the feminine and sensual side of human nature. While the focus is primarily on Goldmund, the novel occasionally examines Narcissus’s perspective; after all, they represent two contrasting but corresponding sides of human nature. Narcissus represented the masculine side, veering toward the logical. His logical nature prompted Narcissus to reject connection to the primal mother, hence his aversion to sensual and emotional experiences. Together, they form two halves of a whole—the spiritual and the physical, the rational and the instinctual.

Goldmund’s pilgrimage is thus a journey of self-discovery. Through his experiences and artistic expression, he explores the full range of human nature, with all its contradictions and desires. Through art and his sensual nature he was able to find ways to express himself. Goldmund’s journey, however, cannot be fully appreciated without its conjunction to Narcissus’ own journey. Narcissus represents a different journey toward self-discovery, one that was anchored on intellectual pursuits and meditation, i.e., monastic life. He was the embodiment of logic, order, and, discipline. Narcissus, nevertheless, possessed a wisdom that was able to unlock the potential of his mentee. Their contrasting natures underscores the complexities of human nature, a prevalent theme in Hesse’s oeuvre.

All existence seemed to be based on duality, on contrast. Either one was a man or one was a woman, either a wanderer or sedentary burgher, either a thinking person or a feeling person-no one could breathe in at the same time as he breathed out, be a man as well as a woman, experience freedom as well as order, combine instinct and mind. One always had to pay for one with the loss of the other, and one thing was always just as important and desirable as the other.

Hermann Hesse, Narcissus and Goldmund

Dichotomies are prevalent in the novel, with each character’s motivations and pursuits belonging to the opposite ends of the spectrum. It is these binaries, however, that make Narcissus and Goldmund a compelling and propulsive novel. In a way, the novel’s structure is reminiscent of Hesse’s other works, such as Demian, Siddhartha, and The Prodigy. All of these books involved two male characters, who belonged to extreme ends of the spectrum. One character is shrouded in a dignified air, often mysterious. He also serves as a catalyst; in this case, it is Narcissus. The other character is unsure of who he is, i.e., Goldmund. They are on the cusp of self-discovery and it is their intersection with the catalyst that opens new roads or shifts their perspective. This dynamic makes Narcissus and Goldmund a quintessential Hesse novel.

Beyond the dichotomies, the novel also explores different forms of love. Each character’s pursuit reflects a distinct form and definition of love. Goldmund admires Narcissus while yearning for sensual fulfillment. The admiration is mutual, as Narcissus extends a selfless and platonic love toward his young friend. Goldmund’s longing for maternal love, however, creates a struggle filled with guilt and confusion. Narcissus, in contrast, is driven by his love for intellect. The intellectual exchanges between the two young men are equally compelling. They debate the nature of destiny and the dichotomy between mind and heart—conversations that extend beyond the monastery walls. Their dialogues serve as both comfort and pain, binding them together even as it becomes clear that their paths will inevitably diverge.

With its rich complexities, Narcissus and Goldmund is a compelling read that immerses readers in a journey of self-discovery. Brimming with philosophical reflections that grapple with subjects such as death, love, art, and sensuality, the novel is masterfully woven into a lush tapestry by Hesse’s lyrical prose and remarkable storytelling. In Narcissus and Goldmund, Hesse crafts two characters who stand as polar opposites; it is precisely their contrast that makes them so fascinating. The novel is also a meditation on friendship and the importance of genuine human connection. More importantly, through the characters’ individual journeys, Hesse probes the intricacies of human nature, inviting readers to reflect on their own paths and to consider the interplay between intellect and emotion, tradition and innovation. Narcissus and Goldmund remains a timeless and powerful exploration of humanity from one of literature’s most gifted storytellers.

One thing, however, did become clear to him—why so many perfect works of art did not please him at all, why they were almost hateful and boring to him, in spite of a certain undeniable beauty. Workshops, churches, and palaces were full of these fatal works of art; he had even helped with a few himself. They were deeply disappointing because they aroused the desire for the highest and did not fulfill it. They lacked the most essential thing—mystery. That was what dreams and truly great works of art had in common: mystery.

Hermann Hesse, Narcissus and Goldmund

Book Specs

Author: Hermann Hesse

Translator (from German): Ursule Molinaro

Publisher: Picador

Publishing Date: February 1, 2003 (1930)

Number of Pages: 315

Genre: Literary, Historical, Bildungsroman

Synopsis

Narcissus and Goldmund is the story of a passionate yet uneasy friendship between two men of opposite character. Narcissus, an ascetic instructor at a cloister school, has devoted himself solely to scholarly and spiritual pursuits. One of his students is the sensual, restless Goldmund, who is immediately drawn to his teacher’s fierce intellect and sense of discipline. When Narcissus persuades the young student that he is not meant for the life of self-denial, Goldmund sets off in pursuit of aesthetic and physical pleasures, a path that leads him to a final, unexpected reunion with Narcissus.

About the Author

To learn more about the awardee of the 1946 Nobel Prize in Literature, Hermann Hesse, click here.