The Life and Times of an Artist

Off the coast of continental Europe and nestled in the North Atlantic Ocean is the island nation of Iceland. The isolated country has mesmerized people across the world with its surreal natural beauty. Images of the Northern Lights, the aurora, coupled with the nation’s wild terrain—dotted with volcanoes and majestic waterfalls—have captured the imagination of many. It is a land of vivid contrasts. Consistently ranked as one of the world’s happiest countries and boasting one of the highest literacy rates, Iceland is a place everyone wants to visit at least once in their lives. But while its natural beauty put it on the global map, Icelandic literature is also one of the nation’s most enduring treasures. Contemporary Icelandic literature is significantly influenced by medieval sagas, which discuss migrations, settlements, and the histories of prominent Icelandic families. They also serve as important historical resources and have inspired modern works across various genres.

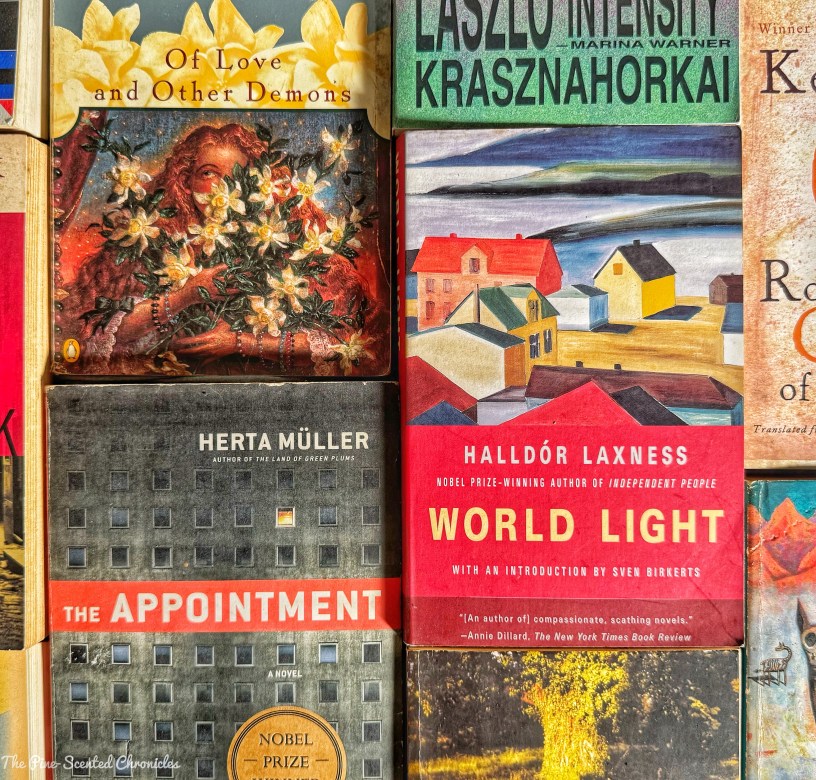

Icelandic literature, however, remained obscure to the rest of the world until the 20th century, when globalization began to take root. A major catalyst in the introduction of Icelandic literature to the wider world was Halldór Laxness. Born Halldór Guðjónsson, he later adopted the name of the homestead in which he was raised. At a young age, his genius had already begun to manifest, and he was determined to be among the world’s top writers. At the tender age of fourteen, he had already seen one of his works printed in a local publication. Three years later, he published his first novel, setting the course for what he was destined for: literary greatness. By the age of thirty, he had published five novels, poetry collections, travelogues, and essay collections. At a young age, he had already achieved a great deal, but he was just getting started. He was resolute in building a literary heritage, and it all paid off in 1955 when his name was immortalized with the awarding of the Nobel Prize in Literature.

In their citation, the Swedish Academy highlighted Ljós heimsins (1937; The Light of the World) as possibly his magnum opus. It is the first of four parts of a novel later published collectively as Heimsljós (World Light) in 1969. Ljós heimsins was succeeded by Höll sumarlandsins (1938; The Palace of the Summerland), Hús skáldsins (1939; The Poet’s House), and Fegurð himinsins (1940; The Beauty of the Skies). World Light charts the fortunes of Ólafur Kárason of Ljósavík, who is first introduced by the shore, staring mournfully into the sea—an immediate sketch of the protagonist. Ólafur has been overshadowed by misfortune from the start. An unloved child, he was placed in the hands of the local parish in northern Iceland after being abandoned in a sack by the person charged with delivering him into the world. His misfortunes did not end there. The young Ólafur was adopted by a boorish family who treated him as an outsider.

Other children had fathers and mothers and honored them, and they prospered and lived to a ripe old age; but he was often bitter towards his father and mother and dishonored them in his heart. His mother had cuckolded his father, and his father had betrayed his mother, and both of them had betrayed the boy. The only consolation was that he had a Father in heaven. And yet—it would have been better to have a father on earth.

Halldór Laxness, World Light

To his adoptive family, Ólafur was ignorant, lazy, and useless. He was bullied by his two older brothers, both vying for control over their powerless adoptive sibling. Meanwhile, his foster parents treated him like a servant, making him hump hay and herd sheep through the worst Icelandic weather imaginable. He found reprieve in Magnina, the family’s daughter, though even she mocked him. It did not help Ólafur’s case that he was sickly, a condition worsened by the taxing physical labor he was forced to perform. Physically and emotionally sensitive, he was unable to meet the demands of farm life. Instead, he found salvation in nature, where, he believed, God manifested himself. Eventually, he experienced visions he thought were signs from God. Through these revelations, Ólafur’s soul found a safe haven—a place of comfort, removed from the world’s harshness—and this retreat allowed him to discover himself.

One day, Ólafur was struck by a mysterious chronic illness that left him bedridden for nearly four years. The light from a small window was among his few comforts. He also found solace in writing. Literature, particularly poetry, helped keep his mind occupied. He wrote about the family, but his foster parents considered his attempts pornographic. Because of his worsening condition, Ólafur was once again transferred to another parish. On his journey, he was assisted by a popular folk poet named Reimar Vagnsson. Taking pity on the young boy, Reimar introduced Ólafur to Þórunn of Kambor, a beautiful priestess who believed in folklore, elves, and fairies. Wrapped in a blanket of mystery, she was confident she could heal him. Lo and behold, her mysticism miraculously restored Ólafur’s health, allowing him to return to the world. The second of the novel’s four parts follows Ólafur as he settles and reestablishes himself in the isolated fishing village of Sviðinsvík.

In his new home, Ólafur continued his journey toward becoming a poet, while the narrative charted his personal growth and development. He immersed himself in village life, his experiences shaped by encounters with the locals. Still, he remained destitute, living a hand-to-mouth existence. He gained new friends—and detractors. He became romantically involved with several beautiful women, only to lose them. He found shelter in the Palace of Summerland, a squatted, abandoned manor house—but the manor was destined to be burned down. Ólafur’s cycle of fortune and misfortune persisted: “Nature had given him the happiness of a blossom. She gave him love and a palace, and put precious poetry into his mouth; it was all one long, unbroken romance. And now everything was lost—his poems, his love, and his palace withered, burnt; forlorn and helpless, he faced the desolation of winter.”

It was at this precarious juncture that someone from his past reentered his life. When he was younger and ailing, Ólafur had met Jarþrúður, an unimpressionable young girl. The novel’s third part moves the story forward five years and captures the marital life of Ólafur and Jarþrúður. The couple had a daughter, only for life to hand them yet another dose of misfortune. Ólafur again found himself engulfed in loneliness. These twists and turns of fate seemed designed to derail his aspirations. His works were deemed unsatisfactory; those around him were indifferent. Yet he did not let these misfortunes waylay him. He surrendered himself to the pursuit of beauty and love. In hardship, he found solace in poetry. His writing and poetic endeavors were his guiding lights in a world shrouded in dark clouds.

To be a poet is to be a visitor on a distant shore until one dies. In the land where I belong, but which I shall never reach, individuals have no cares, and that is because industry runs by itself without anyone trying to steal from others. My land is a land of plenty; it is the world that Nature has given to mankind, where society is not a thieves’ society, where the children aren’t sickly but healthy and contented, and young men and women can fulfill their aspirations because it is natural to do so. In my world it is possible to fulfill all aspirations, and therefore all aspirations are in themselves good, quite unlike here, where people’s aspirations are called wicked because it isn’t possible to fulfill them.

Halldór Laxness, World Light

World Light is a vivid portrait of the life of an artist through the story of Ólafur. In crafting the novel, Laxness drew inspiration from the life of Magnús Hjaltason Magnússon, a folk poet who lived from 1873 to 1916. In a way, World Light is a book about books, featuring several Icelandic poets and writers. Laxness examines the challenges faced by poets and artists, particularly in a society that looks down on them. But Ólafur possessed an indomitable spirit. Ambitious and driven, he remained insouciant toward those who dismissed his dreams. He would live the quintessential life of an artist—embroiled in tumultuous relationships and societal conflicts, even finding himself in the midst of a sexual scandal. He lived in poverty. The novel is an evocative illustration of the tensions between artistic aspiration and societal expectation. The harsh realities of life in rural Iceland ran counter to the pursuit of abstract ideals. These tensions remain relevant today, though not as pervasive as in Magnússon’s time.

The novel explores the many factors that shaped Ólafur’s journey toward becoming a poet. Icelandic people, for one, are devoutly religious. The church in Sviðinsvík is complicit in his struggles, with its miserly pastors the antithesis of godliness. Despite Ólafur’s own religious enlightenment, Christianity was a major obstacle to his pursuit of poetry; devout believers considered poets and poetry blasphemous and filthy. Still, spirituality initially drove Ólafur’s journey. A major spiritual catharsis near the end of the novel reminds readers of this. When incarcerated, Ólafur is visited by a pastor who embodies the kindness and humanity the clergy are meant to uphold: “If I have a face that rejoices in God’s grace, my brother, it is because I have learned more from those who have lived within these walls than from those outside them. I have learned more from those who have fallen than those who have remained upright. That is why I am always so happy in this house.”

Ólafur’s journey was juxtaposed with a period of great uncertainties and upheavals. Social and political forces shape his life and worldview. He witnesses the struggles of socialist ideals against rising capitalism. In the background loom threats of war with the Danes and potential conflict with Norway. It was a period of political turmoil, and Ólafur often found himself at its center. The novel vividly portrays the sociopolitical climate of the time. Unions and labor conflicts were prevalent. The fishing industry, in particular, began to deteriorate due to external interference. Life was a constant struggle. Death and betrayal were ubiquitous. The internal turmoil Ólafur experienced mirrored the turbulence around him. It was a society too embroiled in major problems to care about the works of an obscure poet.

He wrote down everything he saw and heard, and most of his thoghts, sometimes in verse, sometimes in prose. It could take him many hours to write in his diary a survey of one full day: everything was an experience, any noteworthy observation which some nameless person might make was a new vista, any insignificant piece of information was a new sunrise, any ordinary poem he read for the first time was the beginning of a new epoch like a flight around the globe; the world was multiform, magnificent and opulent, and he loved it.

Halldór Laxness, World Light

Lauded by the Swedish Academy “for his vivid epic power which has renewed the great narrative art of Iceland,” Laxness once again made Iceland come alive. The landscape forms an integral part of the novel, vividly painted by Laxness. Iceland’s raw natural beauty stands in stark contrast to Ólafur’s bleak story and the upheavals that plagued the nation. Snow-capped mountains, stormy seas, and hills covered in rolling frozen fog form an idyllic backdrop. Sheep graze in green valleys. Above them, the sharp rays of the sun pierce fluffy clouds. Laxness’s most evocative writing is devoted to exploring the intricacies of Icelandic life, including its internal contradictions. Folklore and superstition—often in stark contrast to religion—were also vital elements of Icelandic culture. The story simultaneously captures the complexities of human nature.

Still, Ólafur remains the backbone of the narrative. His story explores the theme of isolation, imposed on him by a society dismissive of his artistic endeavors. He is a visionary, but various forces push him into loneliness. He grapples with identity and belonging in a world indifferent to his aspirations. His experience is a microcosm of the broader human condition—a yearning for connection and meaning. Yet these circumstances never prevent him from seeking the beauty around him. He sensed, felt, and carried within him the wonder he witnessed. While others were preoccupied with social, political, and economic concerns, Ólafur set himself apart by focusing on beauty. Despite constant challenges, he remained true to himself and his convictions. Along the way, he was supported by memorable characters, including Reimar, who left lasting impacts on his life.

World Light is, at its heart, the life and times of Ólafur. We follow his journey from a mistreated red-haired child to his coming-of-age. While he never attains greatness, his story is filled with discoveries and reflections on life. There is also a redemption arc that adds an intriguing dimension to the narrative. It is a multilayered and multifaceted story that captures the social, political, and economic concerns of a nation on the brink. As much as it is a story about a poet’s journey, World Light is also a novel of Iceland. Laxness paints a nation surrounded by contradictions of beauty and chaos. Indeed, it is a novel riddled with dichotomies: humor—often self-derogatory—and contempt pervade Ólafur’s path; bleakness and sinfulness contrast with themes of spirituality. Despite the odds, Ólafur remains impervious. He rejects chaos and seeks beauty while struggling with worldliness and sensuality. Though the novel drags in places, World Light is ultimately a delightful and engaging story about dreamers who refuse to lose their vision in a world descending into pandemonium.

Thereafter, when he himself was dead, he imagined that his poems would be published in some mysterious way, and the nation would read them for comfort in adversity, as it had read the poems of other poets before him; it was his highest wish that his poems could help those as unfortunate as himself to have patience to endure.

Halldór Laxness, World Light

Book Specs

Author: Halldór Laxness

Translator (from Icelandic): Magnus Magnusson

Publisher: Vintage International

Publishing Date: October 2002 (1937, 1938, 1939, 1940)

Number of Pages: 598

Genre: Literary, Historical

Synopsis

As an unloved foster child on a farm in rural Iceland, Olaf Karason has only one consolation: the belief that one day he will be a great poet. The indifference and contempt of most of the people around him only reinforce his sense of destiny, for in Iceland poets are as likely to be scorned as they are to be revered. Over the years, Olaf comes to lead the paradigmatic poet’s life of poverty, loneliness, ruinous love affairs, and sexual scandal. But he will never attain anything like greatness.

As imagined by Nobel laureate Halldór Laxness in this magnificently human novel, what might be cruel farce achieves pathos and genuine exaltation. For as Olaf’s ambition drives him onward – and into the orbits of an unstable spiritualist, a shady entrepreneur, and several susceptible women – World Light demonstrates how the creative spirit can survive even in the most crushing environment and the most unpromising human vessel

About the Author

To learn more about the 1955 Nobel Prize in Literature awardee and multi-awarded writer Halldór Laxness, click here.