Happy Wednesday, everyone! Wednesdays also mean WWW Wednesday updates. WWW Wednesday is a bookish meme hosted originally by SAM@TAKING ON A WORLD OF WORDS.

The mechanics for WWW Wednesday are quite simple: you just have to answer three questions:

- What are you currently reading?

- What have you finished reading?

- What will you read next?

What are you currently reading?

It’s already the middle of the week — how time flies! I hope everyone’s week is going well. The good news is that we only have two more days to go before the weekend. I hope everyone makes it through the workweek. Also, we are already in the final month of the year. In just a couple of days, we’ll be welcoming the new year. How time flies! With the year approaching its inevitable end, I hope everything is going well for everyone. May blessings and good news shower upon you. I hope the remaining weeks of the year are filled with answered prayers and healing. I also hope everyone is doing well — both physically and mentally — and that you’re making great strides toward your goals. May the rest of the year be kinder to you and reward you for all your hard work.

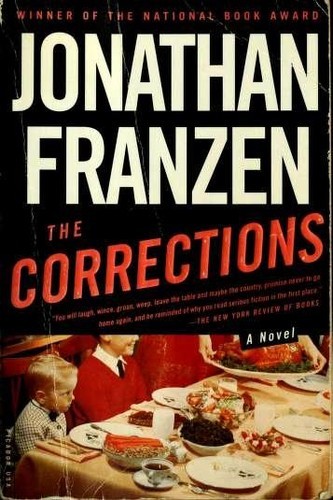

Like in previous years, I have been — and will continue — spending the rest of the year ticking off books on my reading challenges. It has now become a tradition for me to spend the latter part of the year catching up on these goals. At the start of the year, I put together a list of books I want to read no matter what. Since the last two digits of the year are two and five, I came up with a list of 25 books — my 2025 Top 25 Reading List. Among the books on this list is Jonathan Franzen’s The Corrections. This is a book I have long looked forward to reading. Although it was the first book by the American writer that I acquired — nearly a decade ago — it wasn’t the first of his works I read. For this reason, I also included the book in my 2025 Beat the Backlist Challenge. Further, The Corrections is one of the 1,001 Books You Must Read Before You Die. In essence, I am hitting three birds with one stone; it is my goal to read at least 15 books from that list.

Originally published in 2001, The Corrections charts the fortunes of the Lamberts. Typical of Franzen, the Lamberts are a dysfunctional family from the American Midwest. The patriarch, Alfred, is a retired engineer who has developed Parkinson’s and dementia. He is married to Enid, a homemaker, with whom he has three children: Gary, Chip, and Denise. In their own ways, Alfred and Enid’s children have rejected their Midwestern upbringing. They have all moved away from their homeland and distanced themselves from their roots. However, because of the patriarch’s declining health, the family decides to come together for a reunion. I just started reading the book, so I am unable to provide more of my impressions. Nevertheless, I can surmise that Franzen, through the Lamberts, will grapple with concerns plaguing modern America. They will serve as a microcosm of national issues. I will be sharing more of my impressions in this week’s First Impression Friday update.

What have you finished reading?

The previous week was a very busy reading week despite several personal changes taking place. Thankfully, I am finally building momentum and catching up after several reading slumps. In the past week, I was able to complete three books. The first of the three was Nell Zink’s Sister Europe. Before this year, I had never heard of Zink. It was while searching for books to include in my 2025 Top 10 Books I Look Forward To list that I first came across her. Apparently, Zink is an American writer who settled in Germany. She was a long-term pen pal of Avner Shats, an Israeli postmodernist. In 2014, she stepped out of the shadows and finally made her literary debut with The Wallcreeper.

Over the years, Zink managed to build a reputation. Her seventh novel, Sister Europe, is unsurprisingly set in Berlin, the city she has long called home. At the InterContinental, an eclectic cast of characters — primarily Berlin’s exclusive and elusive cultural elite — converges. They gather to honor Masud, an illustrious yet fatuous Arab novelist who has been awarded a $54,000 career achievement prize by an aging royal benefactress, Naema. Over the course of the evening — the entire story unfolds within this timespan — Zink introduces a vivid array of characters: Demian, a German art critic and Masud’s friend; Radi, Naema’s grandson, whom she sends to the ceremony on her behalf; Nicole, Demian’s trans teenage daughter; Toto, Demian’s well-loved publisher friend; and Klaus, an undercover police officer riddled with misunderstandings. Different circumstances have brought these characters together. As the night progresses, their paths cross, and their interactions expose their fears, desires, and even their prejudices. They are all desperately searching for something to do, not only to distract themselves but also to keep the evening from ending too early. The story slowly evolves into a comedy of manners as the focus pans out from the celebrant to the characters surrounding him.

Perhaps it was serendipitous that the characters all found themselves gathered together. As the night takes its natural course, they provide intimate glimpses into their psyches as they discuss a broad spectrum of subjects. Questions about race, gender, sexuality, class, and even dating apps, the war in Ukraine, and Nazism rise to the surface. With the multitude of subjects and themes the novel tackles, each character is imbued with both moral high ground and blind spots. These contrasts make them relatable. Further, there is no clear delineation between the oppressed and the oppressors, as the lines are deliberately blurred. This allows for a free-flowing exchange of ideas. However, the novel tends to meander. These digressions undermine the story at times, creating an underwhelming reading experience. Nevertheless, Sister Europe remains an open-minded book of ideas that examines global concerns.

From Europe, my literary journey next brought me to Nigeria — to a more familiar name and terrain. It was my effort to diversify and expand my reading base that first led me to Ben Okri. In particular, his novel The Famished Road piqued my interest about a decade ago. It became the first of his novels I read, and one of the first works by a Nigerian writer that I encountered. Admittedly, I was a little underwhelmed by The Famished Road, but this did not deter me from wanting to explore more of Okri’s oeuvre, especially after I learned that it was the first book in a trilogy. Eight years after reading The Famished Road, I finally got around to its sequel, Songs of Enchantment.

Originally published in 1993, Songs of Enchantment is set in post-colonial rural Nigeria and reintroduces the familiar character Azaro. Azaro is an abiku, or spirit child — a being whose life is impermanent, destined to die young repeatedly and return to life. However, Azaro is a unique case: unlike his fellow abikus, he chooses to remain in the world of the living, refusing to fulfill his destiny of dying and leaving his family in grief. His desire is to live a normal life. But post-colonial Nigeria is anything but normal. On a personal level, Azaro is plagued by his ongoing connection with the spirit realm. Gifted with the ability to see and speak to spirits, he is constantly pressured by his companions to join them in the world of the dead. As much as the novel focuses on Azaro, Songs of Enchantment is equally about the people surrounding him — his family and fellow villagers. His father is idealistic, wanting to uplift his impoverished community and, at the novel’s start, even winning a great fight. He dreams of building a nation where everyone lives equally. His wife, however, is his antithesis, detached from the political developments sweeping through their country. Still, several forces keep these dreams from reaching their full potential.

Azaro’s father becomes increasingly passionate about building a school for his fellow beggars, but his idealism creates tension within the family; he expects them to be as politically conscious as he is. Matters worsen when Azaro’s mother falls under the influence of Madame Koto, a powerful village figure who owns the local bar — a central setting for much of the action and for Azaro’s unfolding education. The villagers, led by Azaro’s father, begin to grow more enlightened, yet they remain weighed down by a corrupt system in which the powerful and wealthy keep the poor firmly subjugated. The story of the village becomes a microcosm of contemporary Nigerian history. Once again, the lyrical quality of Okri’s prose shines. In many ways, Songs of Enchantment bridges Nigeria’s past and present: the abiku, rooted in African mythology, represents tradition, while the world around Azaro continues to transform. As he confronts the spirits tugging at him from the other dimension, a rapidly changing Nigeria pulls him in the opposite direction.

The three-book stretch concluded with another unfamiliar name; I suppose I have been alternating between new-to-me and familiar writers. Admittedly, I had no plans to read a work by Cristina Rivera Garza. I had not heard of the Mexican writer until recently, when her name was floated as a possible Nobel Prize in Literature candidate. She was a surprising pick because, in all the years I have been following potential awardees, this was the first time I had encountered her name. Naturally, this piqued my interest, although I did not expect to stumble upon one of her books so soon. I actually came across Death Takes Me only over the weekend. I guess curiosity proved too difficult to resist, so I decided to immerse myself in the book.

Although I had no initial plans to read it this year, my curiosity ultimately prevailed. Originally published in 2008 as La muerte me da, the book became available to Anglophone readers only this year. Death Takes Me opens with a striking passage about castration, foreshadowing the darkness and unusual violence permeating the story. Set in an anonymous Mexican city, the novel begins with a dead body — the first of many. A woman out running discovers a male corpse that has been castrated. The woman, Cristina Rivera Garza, is an academic who is struck by the scene as a kind of bloody spectacle. To her, the crime scene resembles a macabre piece of art. This impression is reinforced by the presence of lines from the Argentine poet Alejandra Pizarnik, whose work appears at every subsequent crime scene. Having witnessed the first crime, Rivera Garza is interrogated by the Detective, a woman assigned to lead the investigation, who is assisted by Valerio. Over the course of the inquiry, they also encounter the shadowy Tabloid Journalist, who happens to be researching Pizarnik. As the details unfold, the narrative begins to resemble an archetypal detective story, particularly as more mutilated male corpses are discovered — all castrated.

No stranger to violence herself, the author subtly weaves personal elements into the story. Yet truth and the search for justice remain elusive, mirroring how femicides are treated in society. This is one of the novel’s most compelling dimensions. Women are often the victims of such gruesome crimes, and these cases frequently grow cold and remain unsolved. They have become so commonplace that they are treated as unremarkable. In a way, Rivera Garza upends societal expectations by examining this social malignancy from the opposite angle. But this is not the only subject she deconstructs. The novel is also an exploration of writing and literature. Its structure resists conventional literary forms, challenging standard methods of interpretation. Pizarnik’s writing is interwoven with the unfolding events — more than just a narrative device, her poems echo the characters’ inner landscapes. The novel’s greatest deviation from convention, however, is its lack of a conclusive ending. Overall, Death Takes Me is an intriguing and thought-provoking work, and it has made me eager to explore more of Rivera Garza’s oeuvre.

What will you read next?