Happy Wednesday, everyone! Wednesdays also mean WWW Wednesday updates. WWW Wednesday is a bookish meme hosted originally by SAM@TAKING ON A WORLD OF WORDS.

The mechanics for WWW Wednesday are quite simple: you just have to answer three questions:

- What are you currently reading?

- What have you finished reading?

- What will you read next?

What are you currently reading?

It’s already the middle of the week — how time flies! I hope everyone’s week is going well. The good news is that we only have two more days to go before the weekend. I hope everyone makes it through the workweek. Also, we are already in the final month of the year. In just a couple of days, we’ll be welcoming the new year. How time flies! With the year approaching its inevitable end, I hope everything is going well for everyone. May blessings and good news shower upon you. I hope the remaining weeks of the year are filled with answered prayers and healing. I also hope everyone is doing well — both physically and mentally — and that you’re making great strides toward your goals. May the rest of the year be kinder to you and reward you for all your hard work.

Like in previous years, I will be spending the rest of the year ticking off books from my reading challenges. It has now become a tradition for me to spend the latter part of the year catching up on these goals. My current read, however, does not belong to any of these challenges. Nevertheless, N. Scott Momaday’s House Made of Dawn is a book I have long wanted to read, especially after Momaday’s passing at the start of 2024. Interestingly, before the pandemic, I had never come across the Native American writer. Through an online bookseller, I discovered House Made of Dawn, which immediately piqued my interest. However, it suffered the same fate as many of my other books: it was left to gather dust on my bookshelf. Apparently, the novel is not only Momaday’s breakthrough work, but it is also widely considered a hallmark of Native American literature—a seminal work that catalyzed the mainstreaming of Native American literature.

At the heart of the novel is Abel, a young Native American who, at the start of the novel, returns to Walatowa, his home in the Jemez Pueblo in New Mexico, following the end of the Second World War. Suffering from the aftermath of the war, Abel arrives in his hometown emotionally devastated. He is even too drunk to recognize his grandfather, Francisco, his only remaining relative. Francisco is respected in the community and is renowned for being a good hunter and a devoted participant in the village’s religious ceremonies. He raised his grandson after the death of Abel’s mother and older brother, Vidal. While he instilled in Abel a sense of Native traditions and values, the war has inevitably altered Abel’s psyche, irreversibly severing the young man’s connection to the world of spiritual and physical wholeness. The winner of the 1969 Pulitzer Prize, the novel has certainly commanded my attention. I am halfway through and look forward to seeing how the story unfolds.

What have you finished reading?

In the past few weeks, I have been averaging just two books, which is still a great number. The first of the two books I read in the past week is Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Dream Count. It was while researching books to include on my 2025 Top 10 Books I Look Forward To list that I learned about the Nigerian writer’s latest release. It was through must-read lists that I was first introduced to Adichie, with my venture into her body of work commencing in 2019 with Half of a Yellow Sun. That book won me over, hence my further foray into her oeuvre. Dream Count is the third of her novels that I have read. Honestly, I was initially reluctant to read Dream Count due to the controversies surrounding Adichie, particularly vis-à-vis her stance on feminism. Nevertheless, I overcame this reluctance, making Dream Count part of my reading year.

Divided into five sections, Dream Count charts the fortunes of four women. The first character—and the backbone of the story—is Chiamaka, or Chia for short, a travel writer born to a Nigerian family who currently resides alone in Maryland. Her parents and twin brothers are still in Nigeria. At the start of the novel, the COVID-19 pandemic strikes, altering the landscape of humanity. Chia tries to adjust to these changes, keeping in touch with her family through Zoom calls. However, each call only leaves her feeling lonelier. It becomes evident that there is a missing piece in her life, and these calls serve as catalysts for a string of reflections. Indeed, the pandemic sets into motion a universal experience: a moment of self-reflection. The silence that envelops her prompts introspection about her life. Her loneliness and the seeming meaninglessness of her days make her wonder whether her life is going to waste. Meanwhile, her friend Zikora, a lawyer in Washington, D.C., is grappling with a crisis of her own. Following her announcement of her pregnancy, her partner, Kwame, flees from her home and goes incommunicado. Zikora’s mother travels from Nigeria to oversee her delivery. Unlike the other women in the novel, Kadiatou—Chia’s housekeeper—is a poor Francophone Guinean who grew up in a small village with her parents and sister, Binta. Following a string of tragedies, she moves to the United States with Amadou, her childhood love, in pursuit of happiness and the proverbial American Dream.

The drama intensifies with Kadiatou’s story, which is inspired by the real-life case of Nafissatou Diallo, the hotel maid who accused former IMF head Dominique Strauss-Kahn of sexual assault in 2011. The last of the quartet is Omelogor, Chia’s cousin. Unlike the other three characters, she returns home to Abuja from the United States. Still, her own concerns mirror those of her cousin’s. In a way, all the characters are caught in their own existential crises. Their stories examine the intricacies of love and relationships. Interestingly, their lives are initially anchored on men; however, as the story progresses, the women discover their own strength and resilience amid change. The novel also explores staple themes such as misogyny, abuse, race, and class divides. Kadiatou’s story, in particular, tackles power dynamics and how minorities and victims are often forced into silence, with justice remaining elusive. Subtly, the novel also explores memory, identity, and morality. While not as sharp as the other two Adichie novels I have read, Dream Count fascinates in its topical scope. It carries messages that continue to resonate in the present. Overall, Dream Count is a timely read.

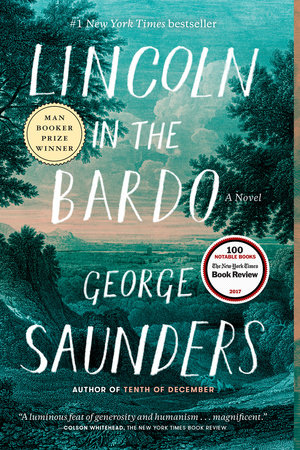

After reading the works of two female Nigerian writers, my literary journey brought me back to the United States. It was the Booker Prize that introduced me to George Saunders. He is apparently a highly heralded writer, though he long skirted full-length prose; his earlier works consist mainly of novellas, short stories and short story collections, and essays. In 2017, he stepped out of his comfort zone and published his first full-length novel, Lincoln in the Bardo, an experimental work conceived after Saunders heard a story from his wife’s cousin. Reportedly, President Lincoln visited his son Willie’s crypt at Oak Hill Cemetery in Georgetown on several occasions to hold the body. The result was a warmly received and critically successful novel.

What immediately stands out in Lincoln in the Bardo is its structure. Rather than following a conventional narrative, the story unfolds through a series of monologues, beginning with the voice of Hans Vollman, a former printer who now exists in the Bardo. The year is 1862, with Abraham Lincoln serving as the sixteenth president of the United States. Vollman explains how he perished, immediately laying out the landscape of the story. Bardo, as I learned, is a Tibetan term meaning “in-between,” a transitional state in Tibetan Buddhism. It is the space between death and rebirth, where ghosts who refuse—or are too frightened—to move on are trapped. Helping Vollman narrate the story is his friend Roger Bevins III. They are just two of the many souls populating the Bardo. These spirits, nevertheless, retain attachments to the real world, which they carry with them into this realm. While the two primary narrators are describing their physical appearances, they take note of Willie Lincoln, a young boy who has just arrived in the Bardo. Believing that children should not remain there, the two men encourage Willie to move on. The boy, however, meekly responds that he feels he is “to wait.” Willie was just eleven years old when typhoid fever resulted in his untimely death in the White House. The two friends, with the help of Reverend Everly Thomas, attempt to free Willie from the Bardo.

Unexpectedly, President Lincoln—Willie’s father—visits the cemetery a few hours after Willie’s burial. Arriving alone, Lincoln cradles his son’s body and mourns, a display of intense affection rarely witnessed by the ghosts. Willie, frightened and lonely, is unable to comprehend his situation and is surprised that his father does not take him home. It soon becomes apparent that Willie is unaware of his own death. This realization forms the crux of the story, as the risk of Willie becoming permanently trapped in the Bardo prompts Vollman, Bevins, and the Reverend to act, lest he remain a ghost bound to this in-between realm. The winner of the 2017 Booker Prize, Lincoln in the Bardo is a compelling and unusual novel. Its historical backdrop provides further depth: in the same year as Willie’s death, the American Civil War has just begun. Lincoln must endure not only the public’s resentment but also the private grief of losing his son. While the country is in turmoil, the ghosts in the Bardo are united by their shared mission to save Willie’s soul. The novel underscores themes of impermanence, grief, and empathy, while also exploring the tension between public and private lives and the beauty of forming authentic connections. Overall, Lincoln in the Bardo is a tender and affecting story about death and the afterlife.

What will you read next?