Just like that, the first month of 2026 has already passed. The first thirty-one days of the year are officially in the books. Recovering from the holiday hangover was quite a challenge, but I hope everyone is already back on track. I also hope the first month of the year has been brimming with blessings, good news, and answered prayers. Personally, I have just started with a new company. It has been rather hectic and challenging, but I am looking forward to what this new environment has in store for me. In many ways, it feels like a fresh start. I hope everyone else is also finding their footing. Either way, I wish everyone well on their individual journeys. For those whose goal is simply to move from one point to another, know that that is perfectly fine, too. I am proud of you and your resilience. In times like these, with so much turmoil surrounding us, silencing the noise can be a challenge. I hope that 2026 will be kinder to you. Above all, I hope everyone stays healthy—in mind, body, and spirit.

To commence my 2026 reading journey, I resolved to venture into the world of Latin American literature. Before the year began, I realized that it had been quite some time since I dedicated a month or two to reading works by Latin American writers. I admit that my engagement with the region’s literature is still somewhat limited, though I have been making a conscious effort to expand my reading horizons beyond popular names such as Isabel Allende, Gabriel García Márquez, and Mario Vargas Llosa. My January literary journey has reminded me of the region’s diversity and rich cultural heritage—both of which make for compelling literature. Despite the dichotomies that exist in the region and the upheavals it has endured in the contemporary period, Latin American literature remains resilient and vibrant, as captured in the works of its most revered writers. Without further ado, here is how my venture into Latin American literature shaped up.

The Melancholy of Resistance by László Krasznahorkai

While I resolved to open the new reading year with works of Latin American writers, my year opener is not actually by a Latin American writer, like last year. The first book I completed this year is László Krasznahorkai’s The Melancholy of Resistance. Reading the book was driven by the Hungarian writer’s recent recognition by the Swedish Academy. It was through the lead-up to the announcement of the 2018 Nobel Prize in Literature that I first came across Krasznahorkai. I was ecstatic when he was finally awarded the prestigious Prize last year. Aside from Sátántangó, The Melancholy of Resistance is often cited as Krasznahorkai’s magnum opus. Originally published in 1989 as Az ellenállás melankóliája, The Melancholy of Resistance transports readers to a run-down Hungarian provincial town with a noticeably apocalyptic air. A palpable sense of hopelessness and despair permeated the atmosphere. The novel opens with Mrs. Plauf enduring a stressful return home. A canceled train service forced her to share a carriage with the unwashed masses. Upon her arrival in the desolate town, a foreboding sense of a disaster striking at any time swept over her. In town, she witnessed lawlessness. The chaos was disrupted by the news of the arrival of a mysterious circus truck. The circus advertises the showing of the body of an enormous whale. Only. Mrs. Plauf sought solace in her orderly apartment. Her sense of harmony was soon disrupted by the arrival of the formidable Mrs. Tünde Eszter. She confides in Mrs. Plauf about her plan to manipulate her estranged husband, György Eszter, through Valuska, Mrs. Plauf’s son. Disowned by his mother, Valuska is the village idiot. Interestingly, the only person who appreciated him is Eszter, a world-weary musician and his former mentor. Eszter’s weariness has become so overwhelming that he has opted not to leave his house. However, his wife, a master of propaganda, wants him to participate in her new project to bring order to the decaying town. Still, the circus looms above the story. It was the representation of chaos. It is a hyperbole, a form of resistance from the seemingly mundane. Powerful symbols riddle the story. It captures the illusion of harmony in a world that is descending into chaos. The Melancholy of Resistance is no easy read, yet it is a worthwhile one.

Goodreads Rating:

Dreaming in Cuban by Cristina Garcia

My foray into Latin American literature officially commenced with Cristina Garcia’s Dreaming in Cuban. A prominent name in American literary circles, it was through an online bookseller that I first came across the Cuban-American writer. Born in Cuba, her family moved to New York City to flee from Fidel Castro’s regime. Still, it seems that she cannot seem to resist the allure of her homeland as she paid homage to it with her debut novel, Dreaming in Cuban. Originally published in 1992, Dreaming in Cuban charts the fortunes of three generations of women from a single family. When she was a young woman, Celia Almeida fell in love with a Spaniard named Gustavo. When Gustavo departed, Celia lost her will to live. At this juncture, Jorge del Pino courted her, and they eventually got married, even though Celia still yearned for her lost love. She often wrote letters to Gustavo; her letters addressed to him alternated with chapters of narration. After getting married, Jorge left his young bride at home with his mother and sister. He often went on long business trips, which served as a punishment for Celia due to her past with Gustavo. Jorge’s mother and sister were also cruel to Celia, especially after she gave birth to Lourdes. The couple would have two more children: Felicia and Jorge. Their children’s paths, however, would diverge as they grow up. Lourdes married Rufino, and they went into exile in the United States, where she became an entrepreneur. Their daughter, Pilar Puente, is an artist and represents the third generation of del Pino women. Meanwhile, her aunt Felicia has embraced santeria and eventually became a priestess; interestingly, she was married three times. On the surface, the novel explores the intricacies of mother-daughter relationships, while underscoring the sense of home. Pilar longs to return to Cuba, while her mother already purged her relationship with her homeland. Still, the fate of the del Pino women was intertwined with Cuba. Political discourses abound in the novel, with the women representing different political ideologies. Beyond politics, the novel explores the Cuban diaspora and the struggles of families in exile. Dreaming in Cuban finds power in its insightful examination of the intersection of politics, immigrant life, and history.

Goodreads Rating:

Home is the Sailor by Jorge Amado

From the Caribbean, my venture into Latin American literature next took me to the mainland. Admittedly, my venture into Brazilian literature is, so far, quite limited. Before doing must-read lists, Paulo Coelho was the only Brazilian writer I was familiar with. Must-read lists introduced me to Jorge Amado. During the first year of the pandemic, I read his novel Show Down. The book left me somewhat confused; still, this did not preclude me from wanting to explore Amado’s body of work further. A couple of years later, I read my fourth Amado novel, Home Is the Sailor. Originally published in 1961 as Os Velhos Marinheiros ou O Capitão de Longo Curso, Home Is the Sailor introduces Captain Vasco Moscoso de Aragão, a master mariner who arrives in Periperi, a suburb of Bahia. The arrival of the titular sailor immediately piques the interest of the locals, as is often the case in small communities. Vasco befriends the townspeople, introducing himself as a retired naval captain, and soon endears himself to them. His stories of distant and exotic ports, sensual women, and daring sea journeys capture their imagination. As in every town, however, there is always someone who remains unimpressed. In Periperi, that person is Chico Pacheco, the town gossip who found the Sailor’s claims implausible—especially as he has been supplanted as the community’s primary storyteller. Convinced that Vasco is merely a braggart, Chico undertakes his own investigation into the Captain’s life, traveling to Salvador to dig into his past. His discoveries and revelations divided the townspeople. Whose version of the truth should they believe? Amid this division, fate leads Vasco Moscoso to command a ship sailing from Salvador to Belém. What follows is a tale of tragedy laced with farce. Still, in classic Shakespearean fashion, all is well that ends well. Humor and satire belie subtle social critiques, with the story capturing the social and economic conditions of Brazil. Amado scrutinized the attitudes and behaviors of Bahian society. A classic odyssey, romantic undertones converged with the Captain’s journey to self-discovery. Often cited as a minor work in Amado’s oeuvre, Home Is the Sailor is nonetheless a refreshing read from the Brazilian storyteller. It offers a different dimension through which to appreciate his body of work.

Goodreads Rating:

Where the Air is Clean by Carlos Fuentes

My venture into the depths of Latin American literature next took me to Mexico. Widely regarded as one of the pillars of Latin American literature, Carlos Fuentes was a writer I kept encountering through online booksellers. During the pandemic, I finally acquired one of his novels. Excited by what the book has to offer, I included Where the Air Is Clear in my 2026 Top 26 Reading List. Originally published in 1958 as La región más transparente, Where the Air Is Clear is Fuentes’s debut novel. Catapulting Fuentes to national recognition, the novel transports readers to 1950s Mexico City, where we are introduced to Ixca Cienfuegos. Deeply rooted in Aztec mythology, he serves as a spiritual guide across the city. He seeks to reclaim Mexico’s ancient past by exacting revenge on the Spanish conquerors, which in the contemporary period pertains to the affluent and powerful. To achieve this, he requires a blood sacrifice. Meanwhile, Gladys García is a prostitute and a direct descendant of the Aztecs. Ironically, their paths never cross. Still, Ixca navigates both the worlds of the elite and the impoverished in search of the ideal sacrifice. This quest leads to an encounter with Federico Robles, a self-made millionaire, a formidable banker who accreted wealth in the aftermath of the Mexican Revolution. He was married to Norma Laragoiti, a green-eyed, self-absorbed materialist, but also took Hortensia Chacón—a blind mestiza woman—as his mistress. Rodrigo Pola is a lawyer who contemplates suicide amid the moral and social decay of the de Ovandos family. The characters’ paths converged at a lively party hosted by Bobo, who gathers the city’s jet set, blending intellectuals, artists, and social climbers into one dazzling social scene. Ixca remains a spectator, observing the transactional nature of the interactions around him with disdain. In the rich Latin American tradition, Where the Air is Clear is infused with elements of magical realism. This allowed Fuentes to explore weighty themes. The 1950s were a pivotal period of social and political transformation in Mexico. Modernization began to reshape the country’s landscape. Ixca offers a perspective rooted in tradition, counterbalancing the forces of change. Brimming with incisive social observation and critique, Where the Air Is Clear stands as a triumph of both writing and storytelling.

Goodreads Rating:

Martín Rivas by Alberto Blest Gana

During the first time I hosted a Latin American literature month, the biggest revelations were the Chilean writers. They allowed me to appreciate Chile beyond the works of Isabel Allende. Their works captivated me, making me more interested in exploring Chilean literature. Among them is Alberto Blest Gana, whose novel Martín Rivas is also part of my 2026 Top 26 Reading List. Before the pandemic, I had never come across this Chilean writer. Originally published in 1862, Martín Rivas is widely acknowledged as the first Chilean novel. Born into a poor family in Chile’s northern mining region, the titular Martín Rivas moved to the capital of Santiago to pursue his university studies. His father, a recently deceased gold-rush speculator, entrusted him to Don Dámaso Encina, his late father’s well-off friend. In the Encina household, Martin’s intelligence and honesty immediately charmed the household. It also helped him gain friends among his peers, particularly Rafael San Luis. Despite his relative youth, Martín’s wisdom was boundless; his friends and even members of the Encina family sought his advice. The novel’s main thread, however, is Martín’s growing fascination with Leonor, the haughty yet beautiful daughter of Don Dámaso. As is always the case, their budding romance is not straightforward. They had a slow-burning romance akin to high school infatuation. Interestingly, everyone around them recognized the sparks between them. However, they keep their feelings carefully obscured. Their relationship, however, is also strongly influenced by the people around them. At the outset, Leonor and Martín are preoccupied with the personal concerns of Matilde, Leonor’s cousin, and Rafael, Martín’s friend. As they attend to the problems of those around them, Leonor and Martín grow closer. Nevertheless, they remain reluctant to reveal their true feelings for fear of rejection. Beyond romance, historical contexts riddle the story. Blest Gana paints a vivid portrait of a young nation reeling from a decade of civil conflict. He captured the social dynamics through his portrayal of class divisions and the exploitation of the lower classes by the affluent. Exploring morality, politics, and friendship, Martín Rivas proves to be a thoughtful and rewarding read that furthers my venture into the depths of Chilean literature.

Goodreads Rating:

The Skating Rink by Roberto Bolaño

Another Chilean writer who has profoundly impacted me is Roberto Bolaño, whose name is a constant presence on must-read lists. While he is best known for 2666 and The Savage Detectives—both of which I have read and loved—I am also keen to explore his other works. With my ongoing venture into Latin American literature, I added The Skating Rink, my fourth Bolaño novel. Originally published in Spanish in 1993 as La pista de hielo, The Skating Rink transports readers to the fictional seaside resort town of Z on the Costa Brava, north of Barcelona. The story unfolds through the alternating narratives of Remo Morán, Gaspar Heredia, and Enric Rosquelles. Remo Morán is a Chilean novelist and poet who immigrated to Spain, where he became a successful entrepreneur. Despite his success, he remains a solitary figure haunted by his past. Gaspar Heredia, also a poet, is a Mexican and Morán’s friend. He lived on the fringes of society as an undocumented immigrant before he was hired by Morán to investigate the world of the homeless; in the process, he befriends illegal immigrants and tourists alike. Meanwhile, Enric Rosquelles is a Catalan bureaucrat. He holds a position of power within the Socialist Party, serving as the mayor’s assistant. He is socially awkward and morally dubious, although all three men have something to hide, making them unreliable narrators. At the center of their story is Nuria Martí, a beautiful figure skater training for the Olympics. He is Morán’s lover. Rosquelles, too, is enamored of her. However, Nuria was suddenly dropped from the Olympic team. Enric then commissions the construction of the titular skating rink in a ruined mansion on the outskirts of town. It was meant to be a monument to his love, but it soon transformed into something far more sinister. The novel is no simple romance story, as corruption emerges as the novel’s overarching theme. It captured how obsession can turn deadly and horrific. Through Heredia, the novel also portrays the plight of immigrants in Spain. Before gaining recognition as a writer, Bolaño himself settled in the Costa Brava, where he worked menial jobs while writing in his spare time. Although not as enchanting as his most renowned works, The Skating Rink remains an engaging and worthwhile read from one of Latin literature’s most influential figures.

Goodreads Rating:

The Volcano Daughters by Gina María Balibrera

It was in 2024 when I first came across Gina María Balibrera, whose novel, The Volcano Daughters, I encountered when literary publications released their lists of the best books of the year. The Volcano Daughters‘ inclusion immediately piqued me because of its haunting cover. The Volcano Daughters is apparently Balibrera’s debut novel. I was also surprised to learn that it is set in El Salvador, a literary landscape I have rarely ventured into. At the heart of the story is Graciela, who was raised by her mother, Socorrito, in destitution on a coffee finca (plantation) on the slopes of Ilzaco, a volcano in western El Salvador. She grows up alongside four girls—Lourdes, María, Cora, and Lucía—who become her closest friends. Graciela’s life was disrupted one day in 1923 when they received a summons from El Gran Pendejo, the dictator whose brutal regime cast a long shadow over the nation. Mother and daughter were ordered to attend the funeral of Germán, Graciela’s estranged father. Abandoning his wife and daughter to begin a new life in San Salvador, Germán rose through the ranks to become the dictator’s advisor. In the capital, Graciela met her sister Consuelo, who was taken from the finca when she was younger, and now lived in luxury with her adoptive mother, Perlita. It was soon revealed that El Gran Pendejo intended for Graciela to assume the position her father once held despite her relative youth. The story unfolded through the voices of the spirits of Graciela’s four friends; the girls later fell victim to the 1932 massacre known as La Matanza. This historical atrocity provides one of the novel’s most powerful contextual layers. Socorrito herself disappeared, while her daughter became a reluctant symbol in the dictator’s propaganda machine. There are several layers to The Volcano Daughters that I find compelling. Beyond the historical contexts that elevated the narrative, I found the references to Salvadoran mythology particularly intriguing. However, The Volcano Daughters slowly peters out as the story progresses. Balibrera attempted to weave together too many themes and cover too much ground. Some plot threads felt fleeting, and the narrative lost focus in places. Nevertheless, I remained enamored of the prose and the integration of magical realist elements—hallmarks of Latin American storytelling.

Goodreads Rating:

The Cemetery of Untold Stories by Julia Alvarez

My literary journey next took me to the Caribbean, to a familiar name in Julia Alvarez. Although I was not as impressed as I had hoped by Julia Alvarez’s debut novel, How the García Girls Lost Their Accent, I did not let this preclude me from wanting to explore her oeuvre further. Her sophomore novel, In the Time of the Butterflies, redeemed her to me. It was in early 2024 that I learned about Alvarez’s most recent release, The Cemetery of Untold Stories. Only recently was I able to acquire a copy of the book. Without ado, I made it part of my ongoing venture into Latin American and Caribbean literature. Alvarez’s seventh novel charts the story of Alma Cruz, a novelist and professor in her sixties. Alma’s mother, however, objected to her writing. Her mother found her portrayal of family life to be slathered with lies. Consequently, Alma publishes under the pseudonym Scheherazade to avoid upsetting her kin. Following their parents’ deaths, Alma and her three sisters learn of their inheritance through the family attorney, Martillo. Their father left them parcels of land in the Dominican Republic. However, the sisters cannot agree on how to divide it, although none of them intended to keep or occupy the land. A random draw resulted in Alma choosing first. Going against the consensus, she chose the largest plot. Located on the outskirts of Santo Domingo, the land was deemed worthless because of its proximity to a landfill and a slum. Alma also elected to forgo any further inheritance, piquing her sisters’ interest. While Alma did not initially plan to choose this piece of land, a plan soon formed in her mind. Post-retirement from academe, she returned to her homeland to seek a quiet existence. On her inherited land, she built a cemetery—not for people or animals, but for her untold stories and the characters she created but never published. Access to the cemetery is limited. The only key is a good story. The first to do so is the enigmatic Filomena, whom Alma eventually hired as the cemetery’s caretaker. With layers of magical realism, Alvarez’s most recent novel once again confronts history. Her literary inquiries lead her to grapple with the question of whose story gets to be written—a challenge to historical documentation, which often sides with the victor. Overall, The Cemetery of Untold Stories is a compelling read.

Goodreads Rating:

The Mambo Kings Play Songs of Love by Oscar Hijuelos

Unlike Alvarez, I have yet to read one of Oscar Hijuelos’s works. Interestingly, they both share the fate of being immigrants; Hijuelos was a second-generation Cuban immigrant whose parents were both from Holguín, Cuba. Before pursuing a full-time writing career, Hijuelos practiced various professions. He did, however, begin writing short stories and plays while working in advertising. In 1983, he published his first novel. However, it was Hijuelos’s sophomore novel, The Mambo Kings Play Songs of Love, that established him as a household name. Originally published in 1989, The Mambo Kings Play Songs of Love charts the fortunes of the Castillo brothers, Cesar and Nestor, talented musicians from a farm in Cuba. In hopes of making a name for themselves, the brothers moved to New York City in 1949. Ambitious and passionate about their music, they soon formed a band—the titular Mambo Kings. Success, however, was elusive. The brothers worked in a meatpacking facility during the day and wrote and rehearsed songs during the night. A serendipitous encounter soon opened doors for the brother. After filming an episode of I Love Lucy, the brothers were set for stardom. The band started performing in prestigious venues, recording albums, and making television appearances. However, this vibrancy in their public lives stood in stark contrast to the turmoil within their personal lives, which were riddled with tragedy and heartbreak. Cesar was charismatic and a chronic womanizer, who had a daughter with his first wife, Luisahim. Cesar continued to send gifts to his daughter, Mariela, in Cuba. Due to his nature, most of Cesar’s romantic connections were fleeting at best. Meanwhile, Nestor’s marriage to Dolores was hampered by his overwhelming passion for music. Essentially antithetical to each other, the brothers were nevertheless bound by their shared love for music. The Mambo Kings Play Songs of Love captures both the struggles and triumphs of the brothers’ lives. With its eclectic cast of characters, Hijuelos’s sophomore novel explores the follies of stardom and how it can alter one’s life, both positively and negatively. Further, the novel delves into deeper themes of cultural identity. Vibrant and dynamic, and at times heartbreaking, The Mambo Kings Play Songs of Love is a notable work, worthy of its 1990 Pulitzer Prize in Fiction.

Goodreads Rating:

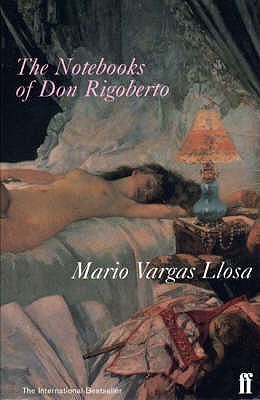

The Notebooks of Don Rigoberto by Mario Vargas Llosa

Concluding my first full month of Latin American literature is a familiar name in Peruvian writer and Nobel Laureate in Literature Mario Vargas Llosa. Must-read lists first introduced me to the Peruvian writer. His works were repeatedly featured on such lists. I later learned that Vargas Llosa is among the leading voices of the Latin American Boom in the second half of the twentieth century. A couple of years later, I have read my fifth Vargas Llosa novel, The Notebooks of Don Rigoberto, a book I also included on my 2026 Top 26 Reading List. Originally published in 1997 in Spanish as Los cuadernos de don Rigoberto, The Notebooks of Don Rigoberto chronicles the life of its titular character. Apparently, the novel is a continuation of In Praise of the Stepmother, which I have yet to read. Don Rigoberto’s story unfolds largely through the perspective of Fonchito (Alfonso), his son from a previous marriage. We learn that Don Rigoberto is an insurance executive during the day, but during the night, he devotes himself to his passionate pursuits. He transforms into a pornographer and sexual enthusiast. In a way, it was his own way of diverting his energies following the emotional turmoil stemming from the absence of his estranged wife, Lucrecia. Doña Lucrecia is his true love. Yet there is more to Don Rigoberto than eroticism. He is deeply fascinated by art and literature. The characters’ fixation on art captures the intersection between sexuality and aesthetics, which is among the novel’s many themes. Still, the central question remains: what happened between husband and wife? We learn that he expelled her after discovering her affair with Fonchito—a scandal depicted in In Praise of the Stepmother. The story is also about Fonchito, who attempts to emulate his father. Obsessed with the decadent painter Egon Schiele, he aspires to become an artist. However, Fonchito is no embodiment of innocence; his veneer conceals manipulative tendencies. The Notebooks of Don Rigoberto explores the interplay between fantasy and reality, portraying eroticism as a means of self-expression. The novel also examines the intimate connections between fantasy, art, and literature, suggesting that aesthetic appreciation is inevitably tied to sexuality. Ultimately, The Notebooks of Don Rigoberto offers a different dimension of the Nobel Laureate’s body of work.

Goodreads Rating:

Reading Challenge Recaps

- 2026 Top 26 Reading List: 5/26

- 2026 Beat The Backlist: 3/20; 10/60

- 2026 Books I Look Forward To List: 0/10

- Goodreads 2026 Reading Challenge: 10/100

- 1,001 Books You Must Read Before You Die: 17/20

- New Books Challenge: 0/15

- Translated Literature: 6/50

Book Reviews Published in January

- Book Review # 628: The Dream Hotel

- Book Review # 629: Shadow Ticket

- Book Review # 630: The Robber Bride

- Book Review # 631: The Secret of Secrets

Historically, January has always been a slow book-reviewing month. In the past three Januaries, I managed to write just two book reviews each. It is a measly output, but January has always been the busiest month at work. Fortunately, some drastic changes this year allowed me to have a January that is more productive than usual. Although I am not yet done with some of my 2025 book wrap-ups, I was able to sneak in time to write some reviews. By the end of the month, I was able to complete four book reviews, the most I had in a January since I published five in 2022. With these four reviews, I was able to make a dent in my 2025 pending book reviews. This, however, means that I still have quite a long way to go before I complete all my 2023 pending book reviews. I did, however, manage to tick off one from the list. Nevertheless, I am still positive I will be able to complete these twenty-eight book reviews within six months; at least that is the goal.

But while I am having a writing slump, my pending list continues to grow. It is not helping that I am reading more than I am reviewing. I hope I get to obtain the writing momentum I built in late January. With all preliminaries nearly done, I hope that my writing momentum will get carried over into February and extend to the rest of the year. For now, my primary focus is to complete my pending June and July 2023 reviews while trying to work on some from 2024 and 2025. Occasionally, I might also publish reviews of books I read before I began publishing reviews—such as Haruki Murakami’s Norwegian Wood and Kafka on the Shore, Kazuo Ishiguro’s An Artist of the Floating World, Salman Rushdie’s The Ground Beneath Her Feet, Ian McEwan’s Atonement, and Naguib Mahfouz’s Miramar. These books hold special significance for me as they were the first works I read by these authors.

In February, I will still be focusing on the works of Latin American writers. I have quite a lot of titles I am looking forward to. I am currently reading Angeles Mastretta’s Lovesick, which I have also included in my 2026 Top 26 Reading List. This is my first novel by the Mexican writer, whom I first encountered through an online bookseller. I have also lined up Gabriel García Márquez’s News of a Kidnapping, Alejo Carpentier’s The Kingdom of this World, José Donoso’s The Mysterious Disappearance of the Marquise of Loria, and Manuel Puig’s Pubis Angelical. I am also considering Isabel Allende’s latest novel, although I have yet to acquire a copy of it. I am looking forward to how Latin American and Caribbean literature will take me on a memorable ride. I will also be reading any book that will catch my fancy, so long as it aligns with my current reading motif.

How about you, fellow reader? How is your own reading journey going? I hope you enjoyed the books you have read. For now, have a great day. As always, do keep safe, and happy reading, everyone!