Of Vibrant Bahian Life

Crazy football culture. Colorful Mardi Gras. Samba. Christ the Redeemer. Capoeira. Copacabana and Ipanema. The Amazon Rainforest. These are just some of the things that come to mind when one is asked about Brazil. They have become symbols of the most populous and largest country in South America. From festivals, sports, and beaches to natural wonders, the country’s diversity underscores its rich and colorful culture. Under this vast umbrella are different groups of people who individually contribute to this vibrant cultural mosaic. In the Amazon rainforest live Indigenous tribes, some of whom remain untouched by technology and modernization. Some of these tribes are even undocumented, highlighting how much of the rainforest remains unexplored. This stands in stark contrast to the pandemonium and fast-paced life of the country’s megacities, such as São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, Belo Horizonte, and even the capital, Brasília.

Brazil’s diversity and colorful culture provide a rich mantle for its writers. Brazilian literature began to take shape during the colonial period, and earlier works followed the literary trends of Portugal. Eventually, however, Brazilian literature diverged from its Portuguese roots. In the 19th and 20th centuries, it assumed a distinct personality separate from the main Portuguese canon. Writers shifted toward a more authentic and uniquely Brazilian style. Over the succeeding centuries, Brazil has produced several prominent names in world literature, including Machado de Assis, Clarice Lispector, Lygia de Azevedo Fagundes, Ferreira Gullar, and Manoel de Barros. Poets Gullar and de Barros were nominated for the prestigious Nobel Prize in Literature. In 2016, Fagundes, at the age of 98, became the first Brazilian woman to be nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature.

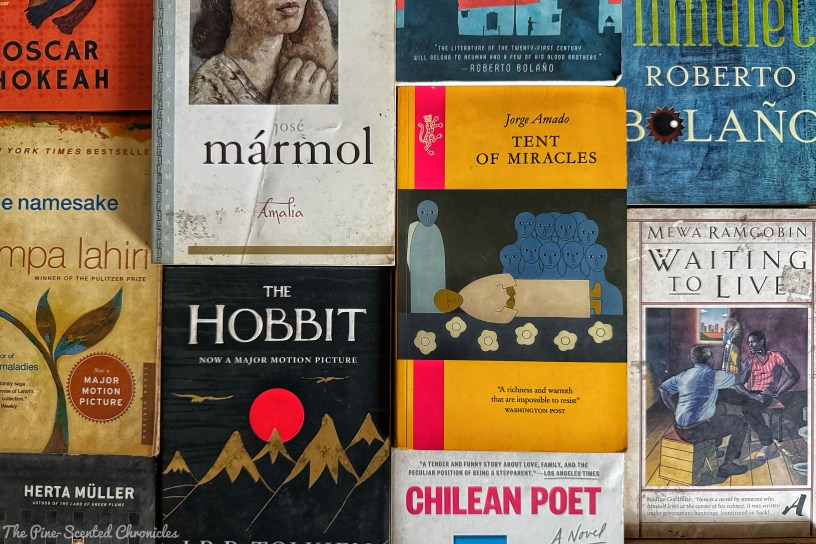

Another prominent name in Brazilian literature is Jorge Amado. Nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature at least seven times, Amado was born on August 10, 1912, on a farm near the inland city of Itabuna in the Brazilian state of Bahia. His interest in writing was cultivated at a young age. By 14, he was already collaborating with several magazines. At 18, he published O País do Carnaval (1931; trans. The Country of Carnival). His second novel, Cacau, was published two years later, further elevating him to national recognition. Politically active, Amado was often exiled for his leftist activities. Nevertheless, this did not prevent him from writing mainly picaresque, ribald tales of Bahian city life. Over a prolific literary career spanning more than six decades, Amado published notable works such as Gabriela, Cravo e Canela (1958; Gabriela, Clove and Cinnamon) and Dona Flor e Seus Dois Maridos (1966; Dona Flor and Her Two Husbands).

When the lights were put out there remained only the matte brightness of the oil lamp shining on the black backcloth, which projected the enlarged shadows of the crude and ingenuous characters onto the whitewashed wall. It was all very simple and simple-minded, and it cost two pennies to see. The show attracted young and old, rich and poor, sailors, day laborers, salesclerks, and shop owners. Some women even came surreptitiously.

Jorge Amado, Tent of Miracles

Among his later works is Tenda dos Milagres (1969), translated into English as Tent of Miracles two years later. It forms part of a series Amado called “The Bahia Novels.” At the heart of the novel is Pedro Archanjo, a forsaken Bahian writer and self-taught social scientist. Weaving in and out of different periods, the novel begins with the arrival of Dr. James D. Levenson, a Nobel Prize–winning professor from Columbia University, in Salvador. It is 1968, which Levenson declares the centennial of Archanjo’s birth; Archanjo had died a few years before the professor’s arrival. Levenson rediscovers Archanjo’s works, which had been largely dismissed during his lifetime. Intrigued by their ethnological merit, he begins researching Archanjo more deeply and claims that his works are seminal to mulatto literature. Levenson’s arrival and bold assertions pique the interest of the local media, prompting them to investigate Archanjo’s life.

In his quest to learn more, Levenson enlists the help of a Brazilian poet named Fausto Pena, whose voice becomes the primary narrative guide throughout the story. The novel then transports readers to Pelourinho—the book’s setting—of the past. The historic center of Salvador, Pelourinho is depicted as a utopia for creative minds: an open-air university where artists, musicians, craftsmen, capoeiristas, poets, and shamans converge. At the heart of this vibrant community, situated near the state’s official school of medicine, is the titular Tent of Miracles. The workshop is run by Master Lídio Corró, who offers spiritual advice in the form of paintings. The Tent also functions as a barbershop, cultural center, artist’s studio, and even a small printing press that publishes Archanjo’s works. Ironically, Archanjo is neither a faculty member nor a student at the university, yet he is one of its most prominent figures and Corró’s close friend.

Before becoming a prominent figure in the university, Archanjo was seemingly ordinary. He was born to a poor mestizo family. When he was still an infant, his father was murdered in Brazil’s war against Paraguay in 1868. As a young boy, Archanjo showed interest in knowledge and scientific insights. However, he never learned science in a formal setting, a derivative of his destitution. Still, he preferred practical knowledge that is self-taught and gained from hands-on learning. In 1900, he was accepted to the school of medicine, not as a student but as a messenger. This menial job, nevertheless, allowed him access to academics and their work. Outside the university, Archanjo gained a reputation as a notorious womanizer. A heavy drinker and partygoer, he never married but fathered several children. He eventually died penniless and largely forgotten.

Yet his unremarkable death does not diminish his legacy. While working as a messenger, he used his spare time to study Bahian culture and its African influences. In 1904, he began publishing his research. He would publish three additional anthropological works on Afro-Brazilian life by 1928. However, his scholarship met strong opposition. Professor Nilo d’Ávila Argolo de Araújo, an avowed racist, was especially critical. Argolo challenged Archanjo to a reactionary debate, defending his theory of Aryan superiority. He firmly believed the Aryan race was inherently superior and best suited for intellectual life. Argolo was eventually discredited when Archanjo’s research revealed that he and the professor shared a common Black ancestor—a revelation that humiliated him. Nevertheless, Archanjo’s writings were largely ignored during his lifetime until Levenson rediscovered them.

It was a sorry era, in which medical writers were more interested in the rules of grammar than the laws of science, better at placing pronouns correctly than handling scalpels and microbes instead of fighting disease. They did battle against French idioms, and instead of investigating and combatting the causes of endemic illness they invented neologisms. People would be obliged to wear anhydropodotecas instead of galoshes.

Jorge Amado, Tent of Miracles

The novel’s backbone is Pedro Archanjo. In him, Amado has created one of his most memorable and humane characters. The quintessence of a self-made man, Archanjo rises from poverty to forge his own destiny. Despite facing numerous obstacles, he remains resolute in his pursuit of knowledge. While he lived in poverty, he cultivated an intellectually and culturally rich life. In many ways, Tent of Miracles is a character study tracing his journey from humble beginnings. He strived to be better. His inquiries led him to study his own culture; he was born to mixed parents, and he was proud of his mixed heritage. Learning about Afro-Brazilian rituals allowed him to assume the role of being a protector of these cultural traditions. He then earned the sacred title Ojuobá (Eyes of Xangô, or Eyes of the King); he was a devoted practitioner of Candomblé, the Afro-Brazilian religion

Archanjo is not merely a chronicler of culture. His works document the traditions of Afro-Brazilians, the mulattos. His works also challenged the dominant “white science” that seeks to suppress and erase them. His reactionary debate with Argolo exemplified this. Their debate also underscored the hypocrisy that often permeates academia. Argolo’s prejudice fuels racial, economic, and political division—maladies that persist beyond the novel’s early 20th-century setting. These are prejudices that persist in the contemporary period. These are also social maladies that Archanjo advocated against. Another form of oppression emerges through the authoritarian police chief, Pedrito Gordo. Ultimately, Archanjo’s defense of miscegenation leads to his imprisonment. Archanjo then develops as a powerful symbol of resistance against these forces that stymie Archanjo and his fellow.

Racism reverberates throughout the novel, transcending time. The opening sequence highlights this. Levenson’s arrival and his claims spark a local media frenzy. In the hopes of elevating Archanjo as a new cultural hero, they did their own research about him. They were hoping to capitalize on the celebration of his life. Ironically, upon uncovering his provenance and the ideals he espoused, advertisers were prompted to create their own vision of Archanjo, attempting to sanitize his image for commercial gain. Riding the wave of Archanjo’s newfound popularity, the advertisers enlisted the assistance of academics who barely had any iota of knowledge about Archanjo. Like Levenson, they appear more interested in self-promotion than in honoring Archanjo’s scholarship or causes.

In many ways, Archanjo serves as Amado’s conduit. Through him, Amado celebrates the vibrant mulatto culture of Bahia. Through his literary works, Amado chronicled the diverse culture of his homeland. Cultural identity lies at the heart of Tent of Miracles. Bahian life itself becomes a prominent character. Certain portrayals, particularly of women, however, feel dated and occasionally objectifying. Still, Archanjo’s odyssey underscores the importance of preserving cultural heritage. Archanjo documents rituals, music, carnivals, and oral stories, embedding African spirituality and myth into the narrative. What Archanjo has unveiled is a lush cultural tapestry teeming with life that he wants to be passed down to future generations, in light of the oppression and discrimination that he and his fellows faced from people like Argolo and Gordo.

On the contrary, those who have stopped to the dirtiest tricks are the very ones who insist on the highest standards of decency and integrity — in others, of course. They pose as incorruptible and proclaim their own spotless virtue; their mouths are always full of words like “dignity” and “conscience,” and they are fierce, implacable judges of other people’s conduct.

Jorge Amado, Tent of Miracles

The novel celebrates African-Brazilian culture and its role in shaping national identity while also addressing socio-economic tensions in Bahia. Amado balances cultural exuberance with political critique—one of the book’s greatest strengths. Nevertheless, Tent of Miracles is the story of Pedro Archanjo. The portrait of an anti-hero, he was charismatic and larger-than-life. He was a man of the people, although he was also the portrait of a deviant lifestyle. He has an insatiable lust for life, from sex, good music, food, rum, to loud revelries. His hedonism and spontaneity are stark dichotomies to his academic brilliance. His life is also an examination of the relationship between knowledge and power. He is at once a philosopher-scientist and a simple man of the streets. These tensions animate both his public and private life.

Archanjo is a man of complexities. Still, his bravery loomed. He was a staunch advocate for individual freedom and truth. He was also surrounded by an equally diverse cast of characters who served to highlight his qualities and ideals. His light-skinned illegitimate son, Tadeu Canhoto, adds nuance to the story. His story reflected the struggle for upward mobility and acceptance. Pedro’s friend Lídio Corró stood for loyalty and camaraderie. Like Archanjo, Major Damião de Souza was self-taught. A lawyer and Archanjo’s friend, he also advocated for the poor and their fellow mulattos. Meanwhile, Dr. Zèzinho Pinto, a publisher, represented greed and an enabler for the whitewashing of Archanjo’s image. The stark dichotomies between good and evil are a prevalent theme in Amado’s oeuvre.

Rife with political undertones and cultural touchstones, Tent of Miracles is multilayered. On the surface, it tells the story of a man who resisted racism and oppression. Pedro Archanjo was a folk hero and the portrait of Bahian culture. Beneath that lies a probing examination of Bahian society. Amado, with his astute writing and unsparing lens, dissects Bahian life. Bahian culture, and by extension, the novel, reverberates with life and teems with color. However, it was a culture at risk of suppression. The story was populated by compelling characters from all walks of life, further creating a vibrant and lush tapestry. The novel is a literary smorgasbord that explores crime, religion, art, and the tension between creativity and intellectual authority. Tent of Miracles is quintessential Amado—and a homage to Afro-Brazilian culture and its important place in the Brazilian identity.

On the contrary, those who have stopped to the dirtiest tricks are the very ones who insist on the highest standards of decency and integrity — in others, of course. They pose as incorruptible and proclaim their own spotless virtue; their mouths are always full of words like “dignity” and “conscience,” and they are fierce, implacable judges of other people’s conduct.

Jorge Amado, Tent of Miracles

Book Specs

Author: Jorge Amado

Translator (from Portuguese): Barbara Shelby

Publisher: Collins Harvill

Publishing Date: 1989 (1968)

Number of Pages: 374

Genre: Magical Realism, Historical, Literary

Synopsis

Tent of Miracles introduces us to perhaps Amado’s richest creation – the late, lovably roguish Pedro Archanjo: street-corner Socrates, devoted anthropologist, cult priest, dean of the demi-monde, bon viveur and indefatigable apostle of miscegenation. Yet Archanjo’s “discovery” by one James D. Levenson – gringo, lover, Nobel Laureate – plunges Bahia into fantastic intrigue. Is Archanjo a savant, a seducer of women exquisite beyond the praise of poets, a rum-sodden scoundrel or a redeemer of magical powers?

About the Author

To learn more about one of the most prominent voices and pillars of contemporary Brazilian literature, click here.