Happy Wednesday, everyone! Woah! Just like that, we are already in the third week of the second month of the year. In a couple of days, we will already be welcoming the third month of the year. How time flies! Still, I want to know how your year has been so far. I hope that the year is going well for everyone. It is unfortunate, but we must go back to our realities. Regardless, I hope the rest of the work week will go smoothly.

With this said, the middle of the week also means a fresh WWW Wednesday update. WWW Wednesday is a bookish meme hosted originally by SAM@TAKING ON A WORLD OF WORDS.

The mechanics for WWW Wednesday are quite simple: you just have to answer three questions:

- What are you currently reading?

- What have you finished reading?

- What will you read next?

What are you currently reading?

It’s already the middle of the week, which means we have only two more days until the weekend. I hope everyone makes it through the workweek. Reading-wise, my 2026 reading journey is going as planned. With the month coming to a close, so too is my foray into Latin American and Caribbean literature. It has been quite a memorable journey—one that introduced me to new names while allowing me to revisit familiar literary territories. I suppose the long wait was worthwhile; the last time I dedicated a month to Latin American literature was back in late 2023. I just finished Texaco by Patrick Chamoiseau, and I am about to venture into The Kingdom of This World by Alejo Carpentier. It was through an online bookseller that I first encountered the Cuban writer, and I later learned that he greatly influenced the Latin American literary boom in the latter half of the 20th century.

Apparently, Carpentier is quite a significant figure in Cuban literary circles, although he went into self-imposed exile after being imprisoned for opposing the dictatorship of Gerardo Machado. Imagine my surprise when I discovered that The Kingdom of This World is listed as one of the 1,001 Books You Must Read Before You Die. Although it is only his second novel, it is often considered his magnum opus. As this will be my first book by Carpentier, I included it in my 2026 Top 26 Reading List. Unfortunately, I have yet to start the novel, so I am unable to provide any impressions of it just yet. Still, I am looking forward to discovering what it has in store. If I have not finished it by Friday, I will be sharing my initial thoughts in this week’s First Impression Friday update.

What have you finished reading?

As mentioned, my foray into Latin American and Caribbean literature has led me to revisit familiar names. Among them is Colombian writer Gabriel García Márquez. It has been a decade since I first encountered the immensely popular author and renowned master of the Latin American brand of magical realism. Beginning with One Hundred Years of Solitude, he has become a staple of my literary adventures, especially during and after the pandemic. News of a Kidnapping, the first of a trio of books I completed in the past week, is the Nobel Laureate in Literature’s first work of nonfiction that I have read—although some classify it as a nonfiction novel. In any case, this is the ninth book by García Márquez that I’ve read, making him my most-read Nobel Laureate in Literature. Before picking up this book, which is also part of my 2026 Beat the Backlist Challenge, García Márquez was tied with Kazuo Ishiguro at eight books apiece.

Originally published in 1996 as Noticia de un secuestro, News of a Kidnapping is a journalistic account chronicling the abduction of ten prominent Colombians by Pablo Escobar’s Medellín cartel between 1990 and 1991. As García Márquez explains in the acknowledgments, the book was conceived after his friends Maruja Pachón de Villamizar and Alberto Villamizar approached him about writing an account of Maruja’s kidnapping, to which he agreed. However, while working on the project, he uncovered nine additional kidnappings that had occurred around the same time. This discovery prompted him to move beyond his friend’s story and examine the broader pattern of abductions; he felt it was impossible to separate Maruja’s ordeal from the others. The narrative opens with the kidnapping of Maruja Pachón and Beatriz Villamizar de Guerrero on November 7, 1990. It was initially believed that Maruja was targeted because of her relation to Gloria Pachón, her sister and the widow of New Liberalism founder and journalist Luis Carlos Galán, who was assassinated before the 1990 presidential election for which he was running. As the story unfolds, however, more sinister forces are revealed to be at play. The book also recounts the abduction of Diana Turbay, director of the television news program Criptón, who was taken along with four members of her news team. Her father, Julio César Turbay, was a former Colombian president. German journalist Herold “Hero” Büss was also kidnapped, as were Marina Montoya and Francisco Santos Calderón.

The book captures the hostages’ experiences in captivity while also conveying their families’ efforts to secure their release. These personal stories are set against the broader backdrop of modern Colombian history and society. The assassination of Galán was one of many instances in which powerful voices were silenced. The kidnappings further underscore the culture of violence that permeated the country at the time. A central figure in this atmosphere of fear and instability was Pablo Escobar, leader of the Medellín cartel. It is widely believed that he orchestrated the kidnappings in response to the threat of extradition to the United States, highlighting the significant role the United States played in Colombia’s political landscape. Meanwhile, the rest of the country grappled with domestic terrorism and the proliferation of drugs. There is such a strong novelistic quality to the narrative that I often forget it is a work of nonfiction. Still, the book provides valuable insight into the Colombian drug trade and how it shaped contemporary Colombian society. I am nearly finished with it.

From Colombia, my foray into Latin American literature next took me to Argentina with Pubis Angelical by Manuel Puig. I have often encountered Puig’s work through online booksellers. His novel Kiss of the Spider Woman seemed ubiquitous, though I am not sure why I held myself back from acquiring a copy. I later lamented the missed opportunity when I learned that it is listed among the 1,001 Books You Must Read Before You Die. Through yet another online bookseller, I came across Pubis Angelical. Without further ado, I acquired a copy, as I was curious about the Argentine writer’s body of work and intended to make it part of my ongoing literary journey across Latin America. Interestingly, I had long thought Puig was Puerto Rican. Only recently did I learn that he was Argentine and also a prominent LGBTQ activist. With this novel, he joins the still very small group of Argentine writers whose works I have read—so far.

Pubis Angelical was originally published in 1979. Its opening line alone caught my fancy: “Streaks of moonlight filtered through the curtain’s lace toward the satin pillow, which soaked them up. The hand of the new bride, beside her dark hair, offered its palm up defenselessly. Her sleep appeared serene.” I find it lyrical, and the same can be said for much of the narrative. The novel develops along two major narrative threads. The first follows an anonymous woman referred to simply as the “Mistress,” whose story opens the book. She is a Viennese actress in the years leading up to World War II, ensnared in a marriage to a wealthy German munitions magnate known only as the Master. Described as the “most beautiful woman in the world,” the Mistress soon finds herself swept up in intrigue, with secrets gradually unveiled as the story unfolds. The second narrative thread, which alternates with the first, is set in the 1970s. It centers on Ana, an Argentine woman confined to a Mexican sanatorium while battling cancer. Prior to her admission, she had escaped a troubled marriage. The political upheavals in her homeland further fueled her desire to flee. Ana’s deteriorating health compels her to confront her mortality and reflect on a life complicated by both emotional entanglements and her own fierce independence.

As the novel progresses, subtle connections begin to tie the two narratives together. Both women reflect on their relationships with men—particularly their dependence on men and, by extension, on family for validation and approval. There is also an element of suspense, especially as the Mistress becomes entangled in what appears to be a conspiracy. The novel engages with themes of Peronism, fascism, and political instability. Its political overtones span South America, particularly Argentina and Mexico City. Hollywood also emerges as a symbolic setting—the dream factory of mythic filmmaking, yet equally a place of cynicism and shattered illusions. It is no wonder that Pubis Angelical is often cited as Puig’s work most influenced by pop culture, a recurring motif throughout his oeuvre. These varied elements combine to create an intriguing and compelling reading experience. I hope to explore more of the Argentine writer’s works in the future.

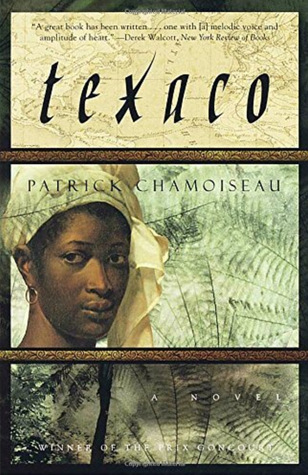

My three-book reading week concluded with another unfamiliar name—at least a writer whose works I had not read before. It was only recently—and yes, through an online bookseller—that I came across Patrick Chamoiseau. A quick search revealed that Chamoiseau is Martinican, from the island of Martinique tucked in the eastern Caribbean Sea. I believe this was one of the reasons I acquired a copy of the book and immediately made it part of my ongoing venture into Latin American and Caribbean literature. This makes him the first Martinican writer I have read. Interestingly, his novel Texaco is the first book originally written in French—Martinique is an overseas department of France—that I have read in over a year. The prospect of exploring a new body of work was more than enough to convince me to dive in.

Originally published in French in 1992, Texaco is set in a shantytown on the outskirts of Fort-de-France, the capital of Martinique. The novel’s primary narrator, Marie-Sophie Laborieux, opens the story in the present. The daughter of a formerly enslaved man, Marie-Sophie recounts her family’s tragic history. Drawing from her father’s memories, his interpretations of the past, and the stories passed down from his ancestors, she reconstructs her family’s history, beginning in the 1820s and extending into the late 20th century. The narrative is framed almost as a myth, with echoes of biblical storytelling. The novel begins with the arrival of a city employee—an Urban Planner named Christ—who subscribes to modernist urban theories that shaped post–Great Depression development and is tasked with “rationalizing” Texaco. His mission is met with resistance from Marie-Sophie, who challenges his assumption that the residents of Texaco are little more than vermin. We learn that Texaco derives its name from the oil tanks in the vicinity. Marie-Sophie emerges as the community’s leader. Orphaned at a young age, she sells fish in the city and works as a housekeeper before eventually building her home in Texaco. In a nonlinear fashion, we learn about her origins. Her father, Esternome, was granted freedom after saving his master’s life, yet he continued to live in poverty and near-servitude. Magic and spirits surround his story, including the zombie of his wife, Ninon, who was killed in the 1902 eruption of Mount Pelée. After the destruction of Saint-Pierre, where they had lived, Esternome moves in with Adrienne Carmélite Lapidaille, a woman from Fort-de-France whom he follows one day in the hope that she might give him food.

Adrienne, however, is no ordinary woman. She is depicted as a witch who enchants Esternome. The spell is broken only when Esternome impregnates Adrienne’s blind sister, Idoménée. Thus begins the story of Marie-Sophie, who is born before World War I. Hers is a story of resilience amid chaos—a narrative that mirrors Martinique’s own tumultuous history, from the struggle to end slavery to the enduring legacy of colonialism. Chamoiseau paints a vivid portrait of his homeland, its people, and its vibrant culture. Texaco serves as a microcosm of the diversity that has long defined Martinique. The interplay of Creole and French underscores the island’s complex cultural heritage. Elements of magic, contrasted with explorations of spiritual identity, add depth to the narrative. Language ultimately emerges as one of the novel’s central themes, highlighting Martinique’s layered and contested history. I admit that I struggled at times with the unconventional structure and the integration of Creole, but overall, Texaco is a rewarding read—one that deepened my appreciation for Martinique, its people, and its history.

What will you read next?