Happy Tuesday everyone! As it is Tuesday, it is time for a Top Ten Tuesday update. Top Ten Tuesday is an original blog meme created by The Broke and the Bookish and is currently being hosted by That Artsy Reader Girl.

This week’s given topic: Things That Make Me Instantly NOT Want to Read a Book

Unfortunately, I cannot immediately name reasons for not wanting to read a book. Because of my adventurous ride, I devour nearly every book I come across although, of course, I have my preferences. For instance, I rarely read works of science and young adult fiction. While belonging to these genres makes me think about reading a book, it does not necessarily disqualify them from being part of my reading list. As such, I decided to feature books I nearly did not finish had it not been for my resolve to complete each book I started. Happy Tuesday! Happy reading!

One Hundred Years of Solitude by Gabriel García Márquez

Kicking off this list is one of my most memorable reads, and not for the reasons you think of. Nobel Laureate in Literature Gabriel García Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude is simply one of those books that upon opening you already have an impression that it is going to take you on a magical rollercoaster ride. It tailspins and swirls in different directions. To be honest, I was overwhelmed by the book at the onset because it was a new world to me. It was basically my baptism of fire, at least where magical realism is concerned. I found myself mentally limping at the start because I was still finding my footing with the nuances of this particular genre. The reading became more pleasurable when I got over the preliminaries and what unfolded is a complex, complicated yet highly entertaining story.

Soul Mountain by Gao Xingjian

From one Nobel Laureate in Literature another. What do their works have that makes them such challenging reads? HAHA. Like in the case of One Hundred Years of Solitude, I bought Gao Xingjian’s Soul Mountain sans any idea about who the writer was or what the book was about. One of the few things that attracted me was the Nobel Prize in Literature on the cover, although I wasn’t as interested in the Nobel Prize in Literature back then as I am now. I was initially daunted by the book’s length, followed by my lack of forays into Gao’s oeuvre but I persevered with the book, hoping that it would take me to territories I rarely venture to. Sure enough, it did. What prevailed was an intimate and adventurous account of rural China. It was certainly not an easy read but getting lost in its labyrinth can be worthwhile.

1Q84 by Haruki Murakami

I can still recall when I finally bought my first Haruki Murakami book; I kept hearing wonderful things about the Japanese writer. Like One Hundred Years of Solitude, 1Q84 was like a baptism of fire as it was my initiation into the world of magical realism. It was also my primer into the works of Haruki Murakami, which is kind of a risk because I could have easily stopped reading more of his works because of 1Q84. It aroused a mixture of emotions – amazement at the varying elements, excitement at the new experience, and even exasperation at its sheer length. On the surface, it seems a very complicated story but when reduced to bite sizes, it is a very simple story. The different elements, especially the surrealism, made it a complicated and complex story.

The Vegetarian by Han Kang

Continuing the trend of first books. Back in 2016 and 2017, Han Kan’s The Vegetarian was making waves. I kept encountering positive feedback about it. In no time, it was part of my own reading list. The book revolved around choices, just as our quotidian existence is always governed by them. The inevitability of choices is something that we deal with on a daily basis. However, there are choices we make that are drastic and radical. It takes a lot of heart to stand by these choices because they will always carry consequences. I was torn about the book after I read it. I was left with more questions than answers. It is quite a quirky read and I’d like to say I enjoyed it but I felt like there was a disconnection between the book and I. But as the years passed by, I started appreciating the book’s subtle but powerful messages, messages that I missed the first time around.

Infinite Jest by David Foster Wallace

A conversation about the most difficult books to read would not be complete without David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest. Despite this caveat, I wanted to check out what the deal was about. Writing a proper review for this colossal work is difficult because there is no superlative that will suffice in describing this book’s compelling qualities. Just simply being able to complete Infinite Jest is a lofty accomplishment. This is one of those very rare books that you would be proud of completing even if you were not completely sure of what you have just read. It is an overly complex and perplexing narrative that both captures and confuses the imagination. It is one of the rare works that gave me several “what the eff” moments. It was humorous and satirical but at the same time deeply melancholic.

Anna Karenina by Leo Tolstoy

A couple of years ago, one of the books I have been looking forward to was Leo Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina. Back then, Russian literature was like a wilderness for me – to some extent, it still is – because I have never ventured into it. There was also something about Anna Karenina that lured me in. With high spirits, I started reading this beloved classic. However, I was left baffled by many elements of it. I felt the story was mundane although I loved the setting. I was perplexed even after I finished reading it; I wanted to it down as it was barely making any sense. I must admit, my appreciation of different cultures and of literature was limited back then. Like in the case of The Vegetarian, and I must say, of Gustave Flaubert’s Madame Bovary, I started to appreciate the story and the plights of the titular Anna Karenina. If I find the time, I just might reread the book and rediscover things that I did not discover the first time around.

Moby Dick by Herman Melville

It is without a doubt that Herman Melville’s Moby Dick is a literary classic, by some measures. However, I’ve always found it fascinating how it could have very low ratings on Goodreads. Despite the low ratings, I was nonplussed because I still wanted to dive into the book. I wanted to understand what was off-putting about the book. I thought I would find a different answer, but I just found myself utterly confused. The writing and the language are a bit rustic, perhaps archaic at some points. Moby Dick is an innovative literary work but its complexities render most of it unreadable. Props to Melville for his visionary writing but he lost me with the tedious encyclopedic knowledge about the whaling industry. Whilst it was fascinating, it was also exasperating and very difficult to get into.

Sophie’s World by Jostein Gaarder

A History of Philosophy. Wow, that was quite a tall order but it was effective in piquing my interest. As such, I included Jostein Gaarder’s Sophie’s World in my 2019 Top 20 Reading List. I was expecting a powerful and insightful narrative. Or at least, interesting. To be fair, the book is really interesting, especially the parts where the history and evolution of philosophy are being discussed. I had high expectations of the book. For the most part, it did well but when I started realizing that there was really no story, everything crumbled for me. It was not even worth trying to dissect how the story concluded,. It spiraled into the metaphysical. “Are we someone’s figment of imagination?”. Honestly, I was disappointed because of my expectations. Props for the philosophy class!

The Little Friend by Donna Tartt

Donna Tartt first captured my interest with her Pulitzer Prize-winning novel, The Goldfinch. It was a book that was not easy to get into because of its length. Moreover, it did not help that it was also my first by the American writer. I did like it despite this, and I also liked her debut novel, The Secret History. As such, I was looking forward to her sophomore novel. Sad to say, I was a little disappointed. Sure, the book was rather thick but it was not the thickness that got to me. What was lamentable was that the promising story was ultimately plodded down by Tartt’s compunction for details. These details were neither helpful in understanding the story nor did they move the story forward. I was about to give up on the story but still pushed forward.

Gravity’s Rainbow by Thomas Pynchon

Thomas Pynchon has long been part of my want-to-read list. His mysterious persona compelled me to seek out his works. This led me to Gravity’s Rainbow, a book that doesn’t leave the readers shortchanged. It is not the average novel for its reputation precedes it. It does have a reputation for being one of those novels that many say they have read but haven’t actually read. But who can blame these readers? Reading Gravity’s Rainbow is an endeavor and one must labor hard to witness it fully unfold. Pynchon wrote an elaborate plot and it takes patience and perseverance to decipher this mammoth novel’s code. Parts-historical, parts-political satire, parts-science fiction, Gravity’s Rainbow is an all-encompassing narrative that redefines what a novel is in ways more than one whilst underscoring a profound message. I don’t know how I was able to find the motivation to finish it but I did.

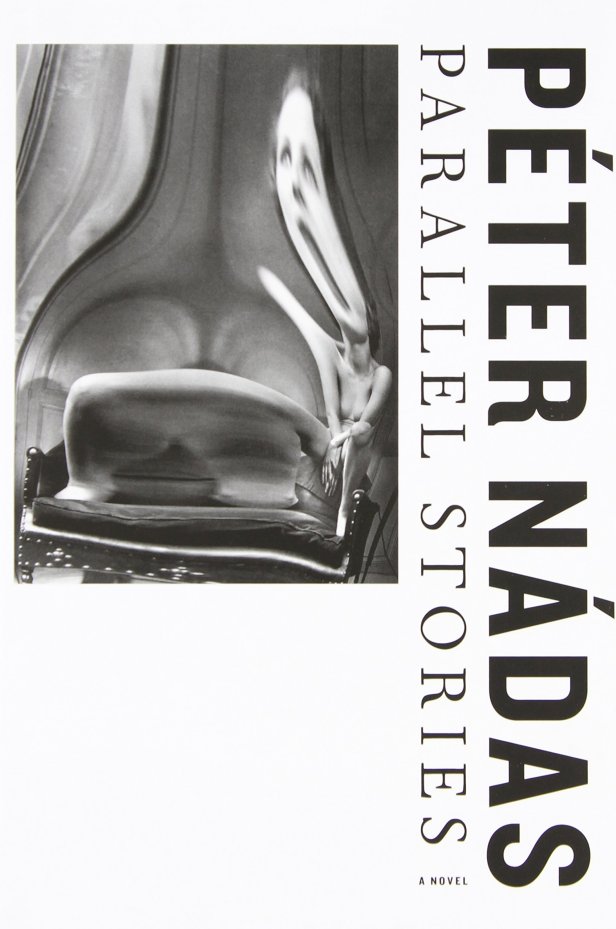

Parallel Stories by Péter Nádas

In the lead-up to In the lead-up to the announcement of the 2018/2019 Nobel Prize in Literature winners I first came across Hungarian writer Péter Nádas. Recall worked for me, and the moment I encountered one of his works – Parallel Stories – late in 2019, I did not hesitate to buy it despite its length. Anticipation and actually reading the book are two different things, as I soon learned. Fetishism abounded in the first half of the story. As each new character is introduced, we would eventually find them colliding into sexual intersections. The story started to resonate with numerous sexual references and images, some were subtle but most were painted vividly to the minutiae. “Cock”, “labia”, and “clitoris” became ubiquitous, and moaning sounds reverberated throughout the story. The smell of semen and urine permeated through every page. The preoccupation with the intricacies of sexual acts was discomfiting. The real story was muddled by these tedious details that seem to be unnecessary.

Past the vivid and graphic images, Nadas riveted me with the intricacies of Hungary, and of how its history intersects with the powers that surround it. To some extent, it was engaging. We are regaled with a plethora of subjects and themes such as family dramas, architecture, opera singing, Nazism, and totalitarianism. It was a smorgasbord that was prepared by Nadas. Like most literary works, Parallel Stories had its fair share of slanders. Nevertheless, it was a rich and lush story that makes me look forward to reading more of the Hungarian novelist’s works.

💜

LikeLike