First Love Never Dies

By this time, everyone has heard of Haruki Murakami (村上 春樹, Murakami Haruki). Many have read his works, particularly those who are devout readers of Japanese literature. After all, his works are ubiquitous, from short story collections to memoirs to novels, each exploring a different subject, with some delving into his personal life. Those who have not read his works would have already encountered his name through casual discussions in literary circles or book clubs. The critical acclaim that his works – such as Kafka on the Shore, The Wind-Up Bird Chronicles, and Norwegian Wood, among others – received made Murakami a part and parcel of conversations related to the Nobel Prize in Literature. It also comes as no surprise that Murakami is one of the, if not the most globally recognized among contemporary Japanese writers.

But while the response to his works is generally positive, some of his fellow Japanese writers are critical of his works. Murakami’s deliberate deviation from the traditional Japanese novel was met with unconcealed disapproval. During the infancy of his literary career, Murakami was not taken as a serious novelist. His works were dismissed as entertainment pieces. Even Nobel Laureate in Literature Ōe Kenzaburō was critical of his oeuvre. These criticisms, however, have never dampened Murakami’s spirits. He kept on doing what he does best: writing. With precision, Murakami created an enviable literary oeuvre that several literary pundits have adjudged as one of the best among living novelists.

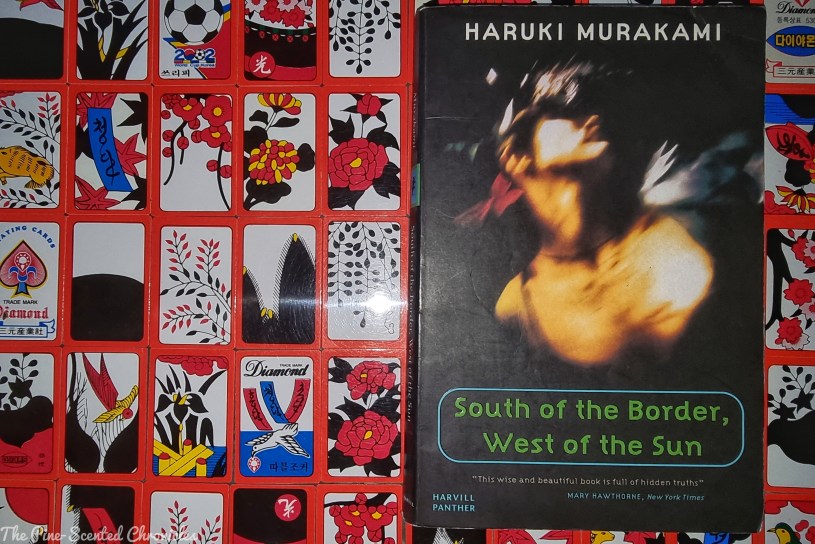

Murakami has been the recipient of many literary awards across the world. Recently, Murakami was awarded the Princess of Asturias Award for Literature, one of the most prestigious literary awards in Europe, and is often considered the Spanish Nobel Prize. In its citation, the Princess of Asturias Foundation wrote that he is a writer who “employs an intimate tone – at times surrealistic and with traces of humour and suspension of belief.” This was a quality of his body of work that was also palpable in his short novel 国境の南、太陽の西 (Kokkyō no Minami, Taiyō no Nishi). The novel was originally published in 1992 and was, later on, released in English in 1999. The English translation by Philip Gabriel – a name that has become synonymous with the works of Murakami – carried the title South of the Border, West of the Sun.

“I was always attracted not by some quantifiable, external beauty, but by something deep down, something absolute. Just as people have a secret love for rainstorms, earthquakes, or blackouts, I liked that certain identifiable something directed my way by members of the opposite sex. For want of a better world, call it magnetism. Like it or not, it’s a kind of power that snares people and reels them in.”

~ Haruki Murakami, South of the Border, West of the Sun

Murakami’s seventh novel, South of the Border, West of the Sun charted the story of Hajime. Born on January 4, 1951, Hajime was part of the post-Second World War generation. Recovering from the damages brought by the war, Japan was experiencing a population bloom. All over Japan, families were having at least two children. It was, for that time, the standard. Hajime, however, was part of the minority, rather, the “unusual ones”: he was an only child of a middle-class couple living in Japanese suburbia. It was the card fate dealt him with but this also made him standout. Among his peers, he was the odd one out. Because of his status as an only child, Hajime was called spoiled, weak, and self-centered by his schoolmates and peers.

Being the only child – and the implications that came with it- has shaped Hajime’s perspective of the world. At a young age, Hajime learned to distance himself from the crowd because whenever he starts integrating, his peers find him strange. He became friendless and developed into some sort of a recluse. It was a quality that he would carry with him as he became an adult. He found comfort in the familiarity of isolation. This spell of isolation was broken by the entry of an unexpected character, the only one he made friends with within six years of studying in elementary school. At the end of their fifth grade, Shimamoto transferred to the school Hajime was attending. She had polio when she was younger but she was also strikingly beautiful. She was also the only person that Hajime got to know very well.

But what bound them together? It was the one thing that they shared. It was in Hajime’s favor that, like him, Shimamoto was an only child. “It was the first time either of us had met another only child.” Although they were polar opposites – Shimamoto was respected by everyone – they quickly strike up a friendship. In each other, they found comfort, pouring out emotions they held inside about being only children. They also talked about life in general and their interests. As they say, all good things come to an end. When they entered junior high school, Hajime’s family moved away. At the start, they tried to make it work but the distance was too much, and eventually, they drifted apart.

Life then took its natural course. Hajime, still reclusive and isolated, entered university. It was at this point that Hajime started exhibiting the stereotypical Murakami male character. He became a drifter with no direction. He joined several causes and university protests. He was involved in several meaningless and failed relationships. A semblance of stability came in the form of the loving and patient Yukiko who he married and had two daughters with. Yukiko was the stereotypical wife who was subservient to the wishes of her husband. She only had one thing in mind: her husband’s happiness. With the help of his father-in-law, Hajime opened a jazz bar which soon became in vogue. It was the place to be in.

“I hurt myself deeply, though at the time I had no idea how deeply. I should have learned many things from that experience, but when I look back on it, all I gained was one single, undeniable fact. That ultimately I am a person who can do evil. I never consciously tried to hurt anyone, yet good intentions notwithstanding, when necessity demanded, I could become completely self-centred, even cruel. I was the kind of person who could, using some plausible excuse, inflict on a person I cared for a wound that would never heal.”

~ Haruki Murakami, South of the Border, West of the Sun

Hajime’s successful business ushered in a new era for him and his family. Just as he was experiencing success in every facet of his life, ghosts of the past started to haunt him. Out of the blue, Shimamoto reentered his life after she read a magazine article featuring Hajime and his jazz bar. Her sudden reappearance naturally upset the harmony that Hajime’s life was currently experiencing. Her presence was threatening the life Hajime built for himself. But it also summoned Hajime’s deeply buried emotions for Shimamoto. Hajime found himself at a crossroads as it slowly dawned on him that he loved Shimamoto. Time has not dulled his feelings for his childhood sweetheart. As Hajime and Shimamoto rekindle their lost romance, what are they willing to lose?

Ah, first love. The halcyon days of innocence and purity. Most of us have experienced the blossoming of emotions at a very young age. It seems puerile but also pure. This was captured vividly by Murakami. His most affectionate writing was reserved in his depiction of the development of Hajime’s feelings for Shimamoto. It started with their playful childhood days when they would listen to tapes by Liszt and Nat King Cole on her father’s stereo on blissful afternoons. Sure, there were moments of uncertainty but he has always been loyal to his feelings for and memories of Shimamoto. She was a face he looked for in the crowd. It was her presence that he longed for. She lingered even as time crawled toward inevitability. But there still lingers that question of what if.

But even as Hajime’s feelings for Shimamoto were consolidated and his plans crystalized, Shimamoto remained an enigma, both to the readers and to Hajime. There was a huge void between the Shimamoto of the present and of the past. Her refusal to fill in the blanks underscored this shroud of mystery. This is very characteristic of Murakami’s prose. Even his wife Yukiko was a passive presence for most of the story. Meanwhile, the other female characters were objectified, again, a common facet of Murakami’s prose, one that has also earned him criticism. The other women in Hajime’s life represented things that he needed at a particular time such as adoration, contentment, and even sex. His feelings for Shimamoto, however, were deep and filled with passion. It was also unequivocally mutual.

Passion, romance, and bittersweet first love were palpably the novel’s overriding themes. It captured the lengths we go to express our love. Along the way, however, someone will have to bear the price. As star-crossed lovers fulfill their destiny, someone is bound to get hurt, unintentionally or not. As consequences manifest and questions of morality arise, philosophical intersections come to the fore. The exploration of the complexities of human nature, an element that Murakami’s prose is known for, also floats to the surface. Beyond its rich romantic overtones, the novel captured the beauty of human connection and the effect people have on each other. There were also commentaries on capitalism and bureaucratic corruption.

“Reading was like an addiction; I read while I ate, on the train, in bed until late at night, in school, where I’d keep the book hidden so I could read during class. Before long I bought a small stereo and spent all my time in my room, listening to jazz records. But I had almost no desire to talk to anyone about the experience I gained through books and music. I felt happy just being me and no one else. In that sense I could be called a stack-up loner.”

~ Haruki Murakami, South of the Border, West of the Sun

In a way, Shimamoto was rendered a ghost-like quality by Murakami. She was absent for decades but suddenly sprang up. She was a ghost that Hajime must exorcise in order for him to move forward. There were regrets for the things we did or did not do but we also have to learn how to let them go. Shimamoto is then a vessel for Hajime to be reassured about the path he was taking. There was a subtle transition from self-centeredness to self-awareness that elevated the story; it was one of the story’s loftiest achievements. Hajime’s development as a character was scintillating to read and witness, even for a deceptively slender novel.

South of the Border, West of the Sun was a paradigm shift in Murakami’s prose. Unlike his earlier works, and even some of the works that succeeded it, South of the Border, West of the Sun was more conventional, in terms of execution and structure. The absence of vivid magical realist elements – an element that Murakami’s major works are embellished with and are renowned for – was glaring. This, however, has not adversely affected the story as Murakami, a brilliant writer of top-notch ability, made it work. The presence of familiar elements such as beer, cats, and Western pop and rock music references, reminds the readers that this is still very much a Murakami novel. Another popular element, Jazz music was also present; half of the book’s title, South of the Border, was from a fictional song by Nat King Cole.

South of the Border, West of the Sun occupies a unique place in Murakami’s oeuvre, at least where execution is concerned. The complexity of the subjects it examined belied its slender appearance. The story of Hajime reminded the readers of the beauty of first love. As the what-ifs slowly become reality, first love can be bittersweet. The lush tapestry of the novel also captured the beauty of human connections, the ugly realities of regrets, and above all, the indelible mark we leave on others. South of the Border, West of the Sun showed a different side of Murakami’s storytelling but it was also a testament to his capabilities as a writer and as a storyteller.

“I always feel as if I’m struggling to become someone else. As if I’m trying to find a new place, grab hold of a new life, a new personality. I suppose it’s part of growing up, yet it’s also an attempt to re-invent myself. By becoming a different me, I could free myself of everything. I seriously believed I could escape myself – as long as I made the effort. But I always hit a dead end. No matter where I go, I still end up me. What’s missing never changes. The scenery may change, but I’m still the same old incomplete person. The same missing elements torture me with a hunger that I can never satisfy. I think that lack itself is as close as I’ll come to defining myself.”

~ Haruki Murakami, South of the Border, West of the Sun

Ratings

81%

Characters (30%) – 25%

Plot (30%) – 22%

Writing (25%) – 22%

Overall Impact (15%) – 12%

Although it was without design, I closed my May 2023 Japanese Literature reading journey in the same way I opened it: reading a novel by Haruki Murakami. While waiting for his latest work to be translated into English, I decided to read Dance Dance Dance – this was deliberate – and South of the Border, West of the Sun – this was unplanned. In reading the latter, I am just one novel away from completing all his novels; the only feather missing from my cap is his most recent. South of the Border, West of the Sun is deceptively thin but packed a lot of punch. Murakami was economical in his words – rather uncharacteristic of him really – but it still worked because he is a naturally brilliant writer. Of the characters, Shimamoto was by far the most interesting. If only Murakami pierced that shroud of mystery that she was wrapped in and allowed the readers to know her more. Overall, it was still a compelling read; Murakami’s works rarely are.

Book Specs

Author: Haruki Murakami (村上 春樹, Murakami Haruki)

Translator (from Japanese): Philip Gabriel

Publisher: The Harvill Press

Publishing Date: 2000 (1992)

Number of Pages: 187

Genre: Literary, Romance

Synopsis

Childhood sweethearts, long ago separated, meet again and innocent love re-awakens as desire, unquenchable and destructive.

Growing up in the suburbs in post-war Japan, it seemed to Hajime that everyone but him had brothers and sisters. His sole companion was Shimamoto, also an only child. Together they spent long afternoons listening to her father’s record collection. But when his family moved away, the two lost touch. Now Hajime is in his thirties. After a decade of drifting he has found happiness with his loving wife and two daughters, and success running a jazz bar. Then Shimamoto reappears. She is beautiful, intense, enveloped in mystery. Hajime is catapulted into the past, putting at risk all he has in the present.

About the Author

To know more about Haruki Murakami, one of the most popular and accomplished names in contemporary literature, click here.

I am really enjoying your work!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you.

LikeLike