The Legacy of Colonialism

In 2021, the Swedish Academy recognized Abdulrazak Gurnah as the honoree for the Nobel Prize in Literature, widely considered as one of the, if not the highest achievements in literature. It came as a surprise to the literary world. early betting odds were topped by more popular writers such as Annie Ernaux (who would join Gurnah as a Nobel Laureate in Literature a year later), Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, Haruki Murakami, Margaret Atwood, and Ann Carson. Salman Rushdie, Stephen King, Hilary Mantel, and Marilynne Robinson were also part of the conversation. Meanwhile, Gurnah flew under the radar and was not even part of any of the Nobel Prize in Literature discourse. But as has been the case, the Swedish Academy went against the grain and deviated from the mainstream.

In a literary landscape proliferated by the works of popular and mainstream writers, the Tanzanian-born writer stood his ground, capturing the landscape and legacy of colonialism in Africa through his novels and short stories. His works, however, did not go unnoticed. His fourth novel, Paradise, was shortlisted for the 1994 Booker Prize while his sixth, By the Sea, was longlisted in 2001. His longtime editor Alexandra Pringle even considered him one of the “greatest living African writers.” Still, Gurnah remained underrated and experienced modest exposure. When Gurnah was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature, Pringle was among those most ecstatic. The recognition was so unexpected that when Gurnah received the call, he thought it was a prank.

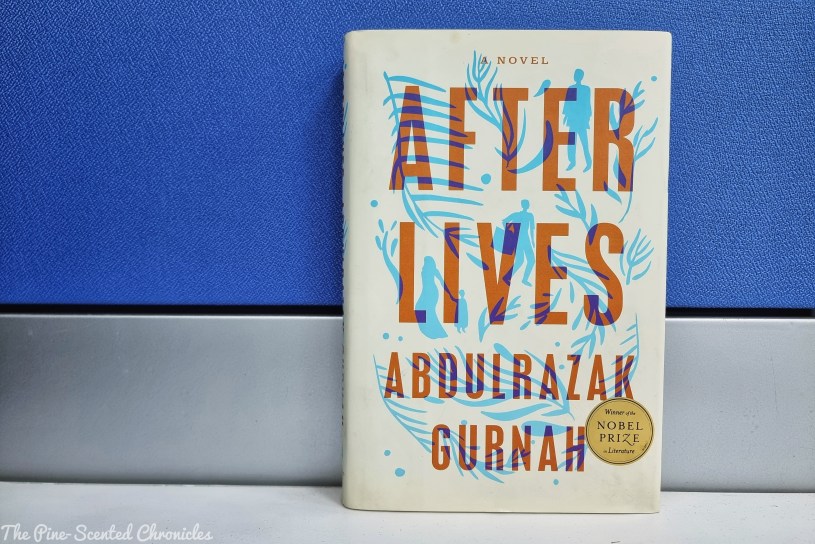

Prior to his Nobel Prize recognition, Gurnah’s works were rarely published outside the United Kingdom; he moved to the United Kingdom when he was eighteen during the Zanzibar Revolution. His works, nevertheless, received critical praise from readers and literary pundits alike. However, they were not as successful commercially. His Nobel win was a catalyst for the renewed interest in his works. Demand for his works exponentially increased, with publishers and booksellers even struggling to keep up with the demand. Among these books was Afterlives, his latest novel, which received bids from American publishers only after his win. It was released in the American market in 2022, two years after its original publication.

“As the askari told their swaggering stories and marched across the rain-shadow plains of the great mountain, they did not know that they were to spend years fighting across swamps and mountains and forests and grasslands, in heavy rain and drought, slaughtering and being slaughtered by armies of people they knew nothing about: Punjabis and Sikhs, Fantis and Akans and Hausas and Yorubas, Kongo and Luba, all mercenaries who fought the Europeans’ wars for them, the Germans with their schutztruppe, the British with their King’s African Rifles and the Royal West African Frontier Force and their Indian troops, the Belgians with their Force Publique.”

~ Abdulrazak Gurnah, Afterlives

In their recognition of Gurnah, the Swedish Academy cited him for his “uncompromising and compassionate penetration of the effects of colonialism and the fate of the refugee in the gulf between cultures and continents.” This was exemplified in Afterlives, Gurnah’s 10th novel. In its exploration of the colonial history of Africa, the novel transported readers to the infancy of the 20th century, to colonial-era German East Africa; East Africa is a familiar terrain in Gurnah’s body of work. This was a period when virtually all of the African continent was occupied by “Europeans, at least on a map: British East Africa, Deutch-Ostafrika, África Oriental Portuguesa, Congo Belge.”

In the seacoast village of Tanga, the readers are first introduced to Khalifa. Born to an Indian businessman and an African woman, he was a diligent student whose German-language speaking skills came in handy when the Germans colonized Tanzania. With some help from his father’s Gujarati connections, he was able to obtain a job in a local bank. Through his job, he caught the attention of Amur Biashara, a merchant he once helped. Amur, recognizing Khalifa’s abilities, offered Khalifa a job in his shady business ventures. Following the death of his parents, Khalifa married Amur’s orphaned niece, Asha; they had never met each other previously until the day of the wedding but they somehow made the marriage work.

Gurnah then weaves intricate and complicated family structures into the novel’s rich tapestry. With the union of Khalifa and Asha, Amur was hoping Khalifa would get more involved in the business. To Amur’s disappointment, Khalifa barely flinched. Meanwhile, Asha resented her uncle for defrauding them of their family home through dubious loans to her father. After Amur’s sudden death, his son, Nassor, took legal action to obtain ownership of Asha’s home. Around the same time, a new character was introduced. Ilyas returned to Tanga, his hometown, after being away for some time. The locals thought he was “kidnapped by the ruga ruga or the wamanga”; the latter pertains to Omani Arabs who immigrated to East Africa while the former are irregular troops scattered all over the region and are often mercenaries.

However, Ilyas admitted that he ran away from home before falling into the arms of the Schutztruppe, the German colonial troops. He was then educated in a German mission school. On his return, Ilyas crossed paths with Khalifa and they became fast friends. Khalifa managed to convince his friend to return to his childhood village. Ilyas relented only to learn that his parents were deceased while his surviving sister, Afiya, lived with an aunt and uncle. The state Ilyas found his sister in was repulsive. Afiya was abused by her caretakers and was living in terrible conditions. Ilyas took her sister with him to Tanga where he taught her to read and write.

“Maybe you will write one day. Maybe you will be able to forget that terrible time one day even if you don’t forget her. Sometimes when I am away from the house I think I will come home and find that you are gone, that you have left me and disappeared without a word. I don’t know if I understand everything about you yet and I am so terrified that I will lose you one day. I lost my moher and father before I even knew them. I don’t know for sure if I remember them.”

~ Abdulrazak Gurnah, Afterlives

Over the horizon, a new threat was brewing. The First World War broke out. Due to his loyalty to the German army – he believed that they were good-hearted and were better than the British army – Ilyas signed up as an “askari” (Tanzanian mercenary). Meanwhile, Afiya was returned to their closest blood relatives, their abusive uncle and aunt. Her salvation came in the person of Khalifa who rescued her after sneaking in a note. Running parallel to the story of Afiya, Ilyas, and Khalifa was the story of another character: Hamza. It was through his perspective, not of Ilyas, that the readers experience the First World War. Hamza joined the German army after escaping from slavery.

It is through the experiences of this eclectic cast of characters that Gurnah examined the heritage of colonialism. His latest novel painted a devastating portrait where terror, war, violence, and exploitation converged. These were all the antithesis of the vision of the colonizers who envisioned bringing “civilization” into the region. Rather, the colonialists’ actions resulted in the oppression of the colonized. Their lands were taken from them. They also had to adapt to the changes instigated by the occupying forces, constantly worrying who was in charge of them. This prompted them to take sides as they were caught in the crossfire between at least two colonizers. Some were indoctrinated and led to believe that one side was better than the other.

At the same time, the colonized had to deal with racial discrimination and slavery that had become prevalent. It was a period of political and economic regression. In the novel, warfare comes in all shapes. They pitted locals against locals, locals against colonizers, and colonizers against each other. We read about the struggle between the Germans and the Brits as they wrestled for control over East Africa. Speaking of warfare, the Maji Maji Rebellion was repeatedly referenced in the story. It is an armed struggle between Islamic and animist Africans and the Germans in Tanzania. Interspersed throughout the story were other historical contexts which reel in the readers.

Personal touchstones were also woven into the novel as the African sentiment was slowly being unpacked by Gurnah. Beyond seminal and timeless subjects of colonization and warfare, vivid details of daily local life in the small community of Tanga rendered the story with different textures. Despite the war and the tumult, life still goes on. Gurnah captured how the locals carried on their lives, working, loving, and learning. The community was a microcosm of the rest region. Tanga was a melting pot for different cultures. Its viability for trading made it a meeting point for other nationalities. Elsewhere, Gurnah’s latest novel captured uprootedness, particularly through the stories of Hamza and Aliya.

“He had lived away from his parents for most of his life, the years with the tutor, then with the banker brothers and then with the merchant, and had felt no remorse for his neglect of them. Their sudden passing seemed a catastrophe, a judgment on him. He was living a useless life in a town that was not his home, in a country that seemed to be constantly at war, with reports of yet another uprising in the south and west.”

~ Abdulrazak Gurnah, Afterlives

The book was also brimming with cultural touchstones. Devotion to the Islamic faith was contrasted with reliance on traditional beliefs in herbalists or mgariga who were often consulted. Locals also believed in necromancers and destiny, that men and women will find each other in birth and death. The novel also touched base on arranged marriages, marriages for convenience, and courtship rites. Meanwhile, the society remained largely patriarchal, with senior male members of the family taking authority by default. Women who received an education were frowned upon by the men of the house. The use of colloquials further provided a sense of place. All of the novel’s wonderful elements were deftly woven together by Gurnah’s straight but evocative writing.

In his most recent novel he wrote prior to being awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature, Gurnah, with élan, wove together a vivid tapestry rich in cultural and historical details. In the true fashion in which the Swedish Academy sang praises for his oeuvre, his latest novel captured how the reckless actions of old empires have oppressed people not only in East Africa but all over the world. Gurnah brought to life a diverse and equally interesting set of characters with complicated lives and dynamics which propelled the novel. From their past traumas and fragmented pasts, Gurnah crafted a stunning story about a subject that has long been close to his heart and his people: the heritage of colonialism.

Book Specs

Author: Abdulrazak Gurnah

Publisher: Riverhead Books

Publishing Date: 2022 (2020)

Number of Pages: 309

Genre: Historical

Synopsis

When he was just a boy, Ilyas was stolen from his parents on the coast of East Africa by German colonial troops. After years away, fighting against his own people, he returns home to find his parents gone and his sister, Afiya, little more than a slave to another family. Hamza too returns home from the war, scarred in body and soul and with nothing but the clothes on his back – until he meets the beautiful, undaunted Afiya. As these young people live and work and fall in love, their fates knotted ever more tightly together, the shadow of a new war on another continent falls over them, threatening once again to carry them away.

Spanning from the end of the nineteenth century, when colonizers carved up Africa, on through the tumultuous decades of revolt and suppression that followed, Afterlives is an astonishingly moving portrait of survivors refusing to sacrifice their humanity to the violent forces that assail them.

About the Author

Abdulrazak Gurnah was born on December 20, 1948, to a Muslim family of Yemeni descent in the Sultanate of Zanzibar which eventually became a part of modern Tanzania. When he was a teenager, the Zanzibar Revolution overthrew the Sultanate and led to the persecution of Arab citizens in the succeeding years. When he was eighteen, Gurnah left Zanzibar for England to seek asylum. He settled in Canterbury where he attended Christ Church College (now Canterbury Christ Church University).

Gurnah received a Bachelor’s in Education in 1976 and then taught secondary school in Dover, Kent, England. He earned his Ph.D. in 1982 from the University of Kent in Canterbury; his thesis was on the topic of “Criteria in the Criticism of West African Fiction.” While completing his doctorate, he taught at Bayero University Kano in Nigeria from 1980 to 1982. In 1985, he joined the University of Kent’s Department of English where he lectured until his retirement as emeritus professor of English and postcolonial literature in 2017.

Gurnah began writing in his early twenties. In 1987, he published his first novel, Departure, after a twelve-year search for a publisher; the novel was originally completed in 1973. His debut novel and his two succeeding novels, Pilgrims Way (1988) and Dottie (1990) documented the immigrant experience in contemporary Britain from different perspectives. His fourth novel, Paradise (1994) is widely considered as his breakthrough work. It was shortlisted for the Booker, the Whitbread, and the Writers’ Guild Prizes. His sixth novel, By the Sea (2001) was longlisted for the Booker Prize. In 2007, the book won Gurnah the RFI Témoin du Monde (Witness of the world) award in France. Desertion (2005) was shortlisted for the 2006 Commonwealth Writers’ Prize. His latest novel, Afterlives, was published in 2020. He also wrote short stories and literary criticisms.

He was the editor of Essays on African Writing 1: A Re-evaluation (1993), Essays on African Writing 2: Contemporary Literature (1995), and The Cambridge Companion to Salman Rushdie (2007). He also held various positions in the literary magazine Wasafiri. In 2006 Gurnah was elected a fellow of the Royal Society of Literature. In 2021, he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature. Gurnah has British citizenship and is currently residing in Canterbury while maintaining close relationships with Tanzania.

📖

LikeLike