Of Love and Healing

Writers, even the most popular ones, are not strangers to using pseudonyms. Except to the devout readers, names such as Mary Ann Evans, Samuel Langhorne Clemens, Eric Arthur Blair, and Charles Lutwidge Dodgson would barely ring a bell of familiarity. To the rest of the world, they are known as George Eliot, Mark Twain, George Orwell, and Lewis Carroll. Each had their own motivations for using an assumed name. Orwell, for instance, wanted to publish under a different name partly to avoid embarrassing his family and partly because he did not like his birth name. Meanwhile, Evans chose to use a masculine name to mask her gender. She was cognizant of how publishers and readers frowned upon female writers. Carroll, on the other hand, wanted to preserve his privacy.

Before they got to be known by their real names, the Brontë sisters, like Evans, used pseudonyms: Currer, Ellis, & Acton Bell. Pseudonyms also grant writers anonymity for political reasons. As such, pseudonyms are also prevalent in times of revolution, uprising, and authoritarian regimes. Revolutionists and activists hid under the cloaks of assumed names to escape political persecution. As history would have it, most of these writers have become more famous under their pen names. The use of pseudonyms is still widely practiced by contemporary writers. Stephen King has published books as Richard Bachman while Nora Roberts is also known as J.D. Robb. Italian novelist Elena Ferrante has become popular for her Neapolitan Novels. Although she has been active in the literary scene since 1992, very little is known about her due to her anonymity.

“We used to have gentlemen in politics. Precious few of them. I wish this chap was a gentleman, but he isn’t, and there it is. If you can’t have a gentleman, I suppose a hero is the next best thing.“

~ Mary Westmacott, The Rose and the Yew Tree

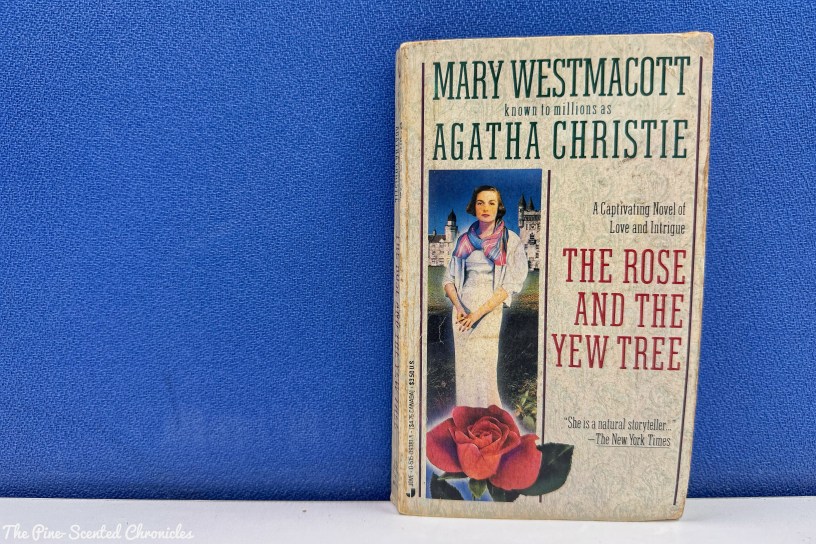

Unbeknownst to many, the famed Queen of Suspense Agatha Christie also published works under a nom de plume, Mary Westmacott. Combining her middle name and the family name of distant relatives, she was able to complete six novels. Among these books was The Rose and the Yew Tree. Unlike most of Christie’s oeuvre, the novel does not star any of the detectives – such as Hercule Poirot, Miss Marple, or Tommy and Tuppence – her works are known for. The Rose and the Yew Tree is also not her typical mystery novel or suspense novel. Using a pseudonym allowed Christie to explore beyond what she has been known for, hence, expanding the scope of her literary landscape. It also allowed her to experiment with her writing.

Interestingly, she published four works as Mary Westmacott without the public knowing her real identity; a journalist revealed her identity in 1949, over two decades after she published her first Westmacott novel. The last of the four books she published before her identity was unmasked was The Rose and the Yew Tree. The novel commences with Hugh Norreys, the novel’s primary narrator in the story’s present as related in the novel’s Prelude. Norreys was an invalid and was in Paris when a woman burst into his life demanding his time. She wanted him to visit a man from Norreys’ past. Norreys wanted to forget about this man and was not keen on meeting the man he loathed. He eventually conceded. With this, the story flashes back to the past as Westmacott details the events that led to Norreys’ resentment.

Before he was an invalid, Norreys was engaged to Jennifer but after their engagement was called off, Hugh figured in an accident that left him crippled and bound to a wheelchair. Due to his condition, Hugh moved in with his brother Robert and sister-in-law Teresa in the sleepy village of St. Loo in Cornwall. In his disability, Hugh found himself unwilling to become the confidant of his visitors. They revealed to him the secrets and emotions they hid from those around them. His condition also made him bitter. He was also bereft of the will to live until he found himself slowly being embroiled in the local political scene. With the local MP election around the corner, one candidate in particular caught his fascination.

The Tory MP candidate, John Gabriel was the subject of Hugh’s curiosity. Driven by his desire for a political career, John entered into an agreement with the conservative party. John was the son of a plumber but eventually gained recognition for being a war hero and a recipient of the Victoria Cross. He was quite the Casanova. He has a way with women. He was not physically unimpressive. Nevertheless, women find his physical attributes, or lack of it, attractive. He compensated for his plain features with his charisma. His public speaking skills were sublime. Beyond his public image, he was ruthless and ambitious. Growing up in poverty, he also felt inferior to the aristocracy, hence, making him resent every royalty he met.

“Imagine to yourself what it’s like to be born a coward – to lie and cheat and get away with it – to love money so much that you make up and eat and sleep and kiss yourwife with money foremost in your brain. And all the time to know what you are…”

~ Mary Westmacott, The Rose and the Yew Tree

Everything was going well for John. What he did not take into the equation was Isabella. Isabella was everything that John was averse to. Isabella Charteris was an orphaned princess who lived in the castle and was expected to marry her cousin, Rupert St. Loo. She was the belle of the ball. She has a calm demeanor and her face rarely shows her reactions. It is rarely apparent what goes on in her mind. Her demure demeanor, however, belies an intelligent mind. She is kind-hearted but she can also be tenacious. She was a woman of contradictions that intrigued both Hugh and, even against his prejudices toward the aristocracy, John. Despite seemingly having a good head above her shoulders, Isabella often engages in acts of self-sabotage, a quality she shares with Christie’s other heroines.

As the individual threads of two polar opposites collide, what ensued was a story that was a step out of Christie’s comfort zone, or at least from what readers typically expect of her and her body of work. Gone is the tenterhook of mystery and the excitement derived from Poirot’s or Miss Marple’s sleuthing. Assuming the persona of Mary Westmacott, Christie was able to repackage herself and, in the process, craft a romance story; all of the six Westmacott novels are romance stories. Love was at the heart of The Rose and the Yew Tree. However, these are neither conventional nor simple romance novels, as can be surmised from The Rose and the Yew Tree. In Isabella and John, the readers meet two polar opposites. With the book’s title derived from a poem by T.S. Eliot, the titular rose was Isabella while John was the yew tree.

The disparity in the social classes between Isabella and John was a barrier they had to overcome. John’s desire to rise above his station and political ambition stood in their way; political gamesmanship was also subtly underscored in the story. This was exacerbated by John’s cynicism toward the upper class. However, love has healing qualities. It has a redeeming power that can turn a rock soft. The ferocious patience that is inherent in pure love has the transformative power to ultimately change a person. However, this can go both ways. Love can also cause great pain and when given the power, it can have destructive qualities. It has the power to hurt and transform a wonderful being into a bitter one.

What Christie was able to carry over from her works of mystery to her works of romance was her uncanny understanding of human relationships and psychology. Her keen understanding of human behavior allowed her to create well fleshed-out and complex characters. The dialogues are familiar and the story’s vibe is akin to Christie’s other works. All of these dispel any feeling of ambivalence with her pivot toward a different and unrelated genre. Further, she wove all of the novel’s wonderful elements together with her familiar writing style. It was accessible and a pleasant read although it did not always flow perfectly. Astutely woven into the story are profound but delicate truths about life. These are thought-provoking and give the story a different texture.

“We worry over what we did yesterday, and debate what we do today and what will happen tomorrow. But yesterday, today and tomorrow exist quite independent of our speculation.”

~ Mary Westmacott, The Rose and the Yew Tree

Like the other Westmacott novels, The Rose and the Yew Tree is interesting in more than one way. The most obvious was its deviation from Christie’s penchant for mystery. There was a little suspense but the story was mainly a tragic romance story. The shift can be disorienting at first but familiar elements of Christie’s writing, such as dialogues and psychologically complex characters, slowly reel the reader in. While tackling the complexities of local politics and the follies of social classes, it was able to vividly capture the intricacies of human relationships and connections. Effectively, it was more than a love story although at its heart was the healing and transformative powers of love. The Rose and the Yew Tree is a welcome addition to Christie’s extensive oeuvre. It is a welcome deviation for a well-established writer of Christie’s stature that also underlines her versatility.

Book Specs

Author: Agatha Christie

Publisher: Jove Books

Publishing Date: January 1988 (1948)

No. of Pages: 189

Genre: Romance

Synopsis

Isabella Charteris – lovely, slender, serene as a medieval saint. The princess of Castle St. Loo, gently groomed for her shining knight and bright, untouched future of privilege.

John Gabriel – decorated hero, vulgar opportunist. That he should appear in her life at all spoke of the final chaos of war.

For Isabella, the price of love meant abandoning a dream forever. For Gabriel, it would destroy the only chance ambition would ever offer. What drew them together was something deeper than love.

About the Author

To learn more about Agatha Christie, click here.