Unhealed Wounds

Without a doubt, American literature is one of the most extensive and influential literatures out there. Despite being relatively younger than other established world literature such as Japanese, Chinese, and British literatures, it spans a vast landscape. Throughout history, American literature has grown exponentially. In no time, it has risen from obscurity and established itself as a literary powerhouse. Under this huge umbrella, several subgenres exist and thrive. Several literary movements emanating from the United States led to global literary shifts. From these sprouted some of the world’s most recognized and most-studied literary pieces. Among them are Herman Melville’s Moby Dick, James Fenimore Cooper’s The Last of the Mohicans, J.D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye, Harper S. Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird, Willa Cather’s My Antonia, and Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin, among others. They are seminal literary pieces that have transcended time and physical boundaries. They remain relevant in the contemporary.

American literature has always been a minefield for exemplary writers who, over the years, have crafted some of the most highly-heralded oeuvres and literary credentials out there. Their top-caliber prose and imaginative storytelling captivated a literary audience the world over. Their capabilities elevated them to global prominence and patronage. Who is not familiar with names like Edith Wharton, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Jack Kerouac, Thomas Pynchon, Joyce Carol Oates, Margaret Mitchell, William S. Burroughs, and Louisa May Alcott? They are ubiquitous and their works are praised in various parts of the world. Not to be outdone, Toni Morrison, Louise Glück, William Faulkner, John Steinbeck, Pearl S. Buck, and Ernest Hemingway were awarded by the Swedish Academy with the prestigious Nobel Prize in Literature, long considered the pinnacle of a literary career. In sheer volume and influence, it cannot be denied that American literature is one of the world’s most recognized literatures.

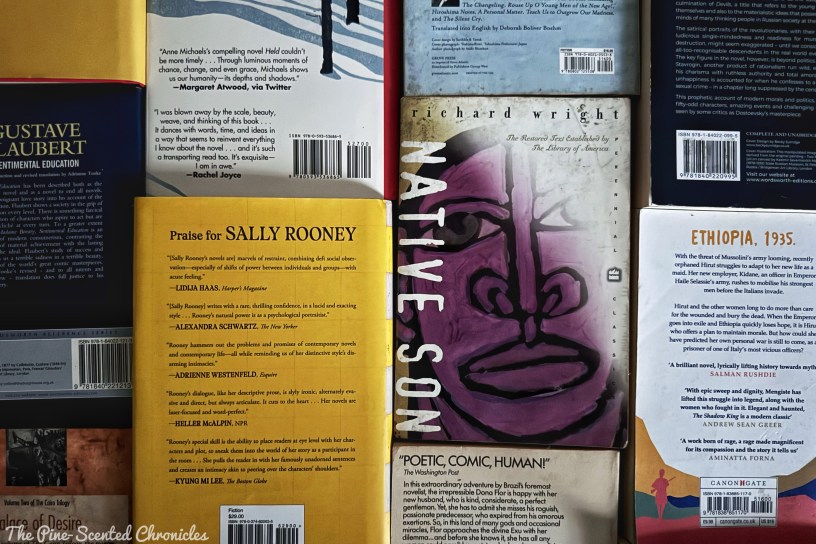

Another prominent name in the ambit of American literature is Richard Wright who is widely regarded as one of the preeminent novelists and essayists of the 20th century. His body of work has helped mold the minds of younger African American writers such as James Baldwin. He is widely considered one of the most important precursors to the Black Arts Movement. Wright first came into the general public’s consciousness with his volume of novellas, Uncle Tom’s Children which was published in 1938. Building from the success of the book, he published what many literary pundits would consider as his magnum opus. Published in 1940, Native Son elevated Wright to a household name. The book’s publication made him the most famous and respected African American writer in the United States during that time. The novel transcends time and remains one of the most recommended literary titles out there.

Rather, I plead with you to see a mode of life in our midst, a mode of life stunted and distorted, but possessing its own laws and claims, an existence of men growing out of the soil prepared by the collective but blind will of a hundred million people. I beg you to recognize human life draped in a form and guise alien to ours, but springing from a soil plowed and sown by our own hands. I ask you to recognize laws and processes flowing from such a condition, understand them, seek to change them. If we do none of these, then we should not pretend horror or surprise when thwarted life expresses itself in fear and hate and crime.

Richard Wright, Native Son

Set in 1930s Chicago, Native Son is divided into three major parts: Fear, Flight, and Fate. In Fear, Wright builds the profile of the novel’s hero, Bigger Thomas, a poor, uneducated, twenty-year-old African American man. He and his family – his mother and two younger siblings, Vera and Buddy – occupied a cramped apartment on the South Side of the city; the area was infamously called the “Black Belt” because of its predominantly African American. Despite his relative youth, Bigger Thomas was gripped by a gnawing realization that his life was at the mercy of other people other than himself. Opportunities for him were limited. He was denied upward mobility because only measly-paying jobs were available to him and those in the same station as him. After a stint at a reform school, he grew bitter and angry about the conditions surrounding him, particularly poverty and racism. Unfortunately, he felt powerless to do anything about it.

Bigger’s mother, on the other hand, was coaxing him to take a job through the relief agency – a chauffeur for a white millionaire philanthropist named Henry Dalton. Along with this came a caveat from his mother to avoid the gang he was a part of. He was not happy about taking a job from the relief agency. Further, it was not a job he wanted. However, Bigger was left with no choice but to accept the job; he was recently kicked out of his gang. Nevertheless, Bigger was left in awe by the sheer opulence of Mr. Dalton’s mansion. The job was decent. At the Dalton mansion, Bigger met Mr. Dalton’s blind wife, the Irish maid Peggy, and Dalton’s blond daughter, Mary. Bigger’s first task, as ordered by Mr. Dalton, was to drive Mary to her lecture at the university that same evening. Mary, however, had other plans. Rather than taking her to the lecture, Mary asked Bigger to take her to her friend, Jan Erlone, a member of the Communist party.

What ensued was a discomfiting tour around the city. It was a new territory for Bigger who was unaccustomed to being sandwiched between two white individuals, including one female. Bigger’s first night on the job ended with Mary’s being so drunk Bigger had to carry her to her room. It was at this juncture that everything went downhill. For Bigger, the succeeding sequence of events – a mixture of sinister, terrible, graphic, and altogether discomfiting images despite the caveat in the novel’s introduction – held unconscionable consequences for him. That fateful night’s events can alter Bigger’s life beyond his imagination. It can be surmised that the graphic details of this sequence are to provide a shock effect. It did quite well in doing that, making the readers flinch. Slowly but with calculated steps, Wright laid out the story’s landscape, steering the readers toward the direction he wanted to lead the story.

The drunken escapade ended on a devastating note. It also forms one of the three key moments in the story. It is, actually, the catalyst for the rest of the story, making the story move forward. The second germane moment portrays Bigger’s candid confession to his lawyer Boris A. Max. Max, a public defender connected to the Communist party, was recommended to Bigger by Jan who was initially insulted and hurt when Bigger tried to set him up. Jan, however, saw it as a springboard to delve further into his own ideals. Bigger’s confession to his lawyer was rawer and brimmed with emotions compared to his confession to the State Attorney David Buckley and even to Reverend Hammond. Bigger’s confession to Max contains the meat of the story. Max, a Jew, made a concerted effort to defend his client. Completing the three important moments in the story is Max’s closing arguments – a soliloquy appealing to the jury’s emotions – which was built on Bigger’s confession and elucidated on the novel’s larger concerns.

If I should say that he is a victim of injustice, then I would be asking by implication for sympathy; and if one insists upon looking at this boy as a victim of injustice, he will be swamped by a feeling of guilt so strong as to be indistinguishable from hate. Of all things, men do not like to feel that they are guilty of wrong, and if you make them feel guilt, they will try desperately to justify it on any grounds; but, failing that, and seeing no immediate solution that will set things right without too much cost to their lives and property, they will kill that which evoked in them, the condemning sense of guilt. And this is true of all men- whether they be white or black -it is a peculiar and powerful, but common need.

Richard Wright, Native Son

Contrary to what one expects, Native Son is not about the miscarriage of justice. It delves extensively into the nature of crime, with the case of Bigger Thomas as a crucible. As his case demonstrated, there are larger factors at play. From the onset, we are given to understand the social inequities that permeate the lives of African Americans in Chicago’s Black Belt. This, however, is a concern that is not local to Chicago because it is shared by many African Americans residing in ghettos in major metropolises across the United States. They are seemingly stuck in a quagmire of poverty from which they cannot take themselves out. Bigger repeatedly aired his frustration at his circumstances and his inability to change them. He felt helpless because he was going against a system that has always pushed to the seams of society. Opportunities to better themselves financially are few and far between. If there are opportunities, they pay meagerly. They must always rely on the support of others.

Because of the inaccessibility of gainful employment some of the African Americans join and form gangs. Bigger was a member of one. Despite the bleakness that surrounded him, Bigger had dreams he wanted to work out. He dreamed of becoming an aircraft pilot. However, he is cognizant that in order to achieve his dream he must conquer several obstacles, such as the abject poverty he grew up in. Further, African Americans in Chicago are discouraged or, worse, not permitted to pursue even a basic education. Bigger had to work twice as hard as his white peers. He had to deal with racism and discrimination. Even with hard work, there is no assurance that he would be able to breach the threshold. Despite his relative youth, a lot weighs on Bigger’s shoulders. He was also cognizant that there are standards of behavior for various groups of people, depending on their color. Native Son is palpably an extensive probe into the virtual divide between white and black and how these two are viewed as polar opposites. One side of the spectrum represents the morally pure while the other side represents the morally fallen.

Bigger is aware of the imaginary boundaries that separate him from white people. These are boundaries he was careful not to cross. Any actions deviating from what was expected from him were viewed with suspicion, or at least as unusual. Driving Mary and Jan around the city made him feel uncomfortable, especially when he was paraded across the Black Belt. He was conscious of how his fellow African Americans would perceive him. In the same manner, he knew that harming white people would come with severe consequences. White people immediately dismiss the factors and motivations driving the actions of African Americans. Mitigating circumstances are not considered because white people immediately view any acts of violence thrown their way as a form of animosity. Bigger recognized this glaring disparity in power dynamics, hence, his acquiescence to the authorities’ – and white media’s – sketch of the events of that fateful night despite major alternations in what really transpired.

Racial stereotypes also drive this. Buckley referred to Bigger as an ape. He also viewed the African American community as unproductive. Buckley echoed the sentiments of the city’s white American population. On the other hand, Mary was Bigger’s antithesis. She was raised in affluence and had been afforded privileges that Bigger did not have. She did not have to concern herself with the same issues that Bigger had to deal with. Her perspective of the plight of African Americans is limited. This, nevertheless, did not preclude her from immersing herself in their concerns, hence, her relationship with Jan which was built on the ideals he advocated for. Nevertheless, Jan and Mary were sincere in their resolve to help and understand Bigger and his plight. Bigger, however, was ambivalent of their crusade given how he was raised. Ironically, Jan and Mary’s socio-political leaning underscores the interest of white Americans in trying to understand racial divides, particularly in the era in which the book was written. It comes off as forced rather than natural despite their sincere efforts.

They came from cities of the old world where the means to sustain life were hard to get or own. They were colonists and they were faced with a difficult choice: they had either to subdue this wild land or be subdued by it. We need but turn our eyes upon the imposing sweep of streets and factories and buildings to see how completely they have conquered. But in conquering they used others, used their lives. Like a miner using a pick or a carpenter using a saw, they bent the will of others to their own. Lives to them were tools and weapons to be wielded against a hostile land and climate.

Richard Wright, Native Son

Politics figure prominently in the story. It was a germane factor that influenced the lives of African Americans. In particular, the novel highlighted two major socioeconomic and socio-political schools of thought: communism and capitalism. People in power’s view of the African American community was encapsulated in Buckley’s view. However, they fail to see how they contributed to the problem. They segregated African Americans from the white population, hence, the Black Belt. The Daltons, who own the housing occupied by Bigger’s family, charged rents that were incomparable with the rates he charged from his white housing. By charging them exorbitant rental fees whilst ignoring the maintenance of the properties they owned and ran, the Daltons and his ilk were major factors in keeping the African Americans shackled to the ground. In a move perhaps to assuage his conscience, Mr. Dalton devotes himself to philanthropic activities, investing in the same community he was earning from. Mrs. Dalton, on the other hand, wished to speak on behalf of their African American maid, their “black help.”

Meanwhile, Jan stood for communist ideas. He was vocal about his political stance. Because of his worldview, he attracted the attention of the authorities. Mary forms the bridge between the two glaring political points of view. However, their efforts to try and save Bigger were born out of impulse, the misguided concept that African Americans needed help because they could not help themselves. They felt the need to help liberate African Americans. It was pure and born out of kindness. However, it was altogether ill-conceived. Jan and Mary’s communist view, therefore, is no different from the view of Buckley and his cohorts. As such, Wright captures the corrosive side of both political schools of thought. Max was sympathetic toward communist ideals and, like Jan, his motivation to help Bigger was pure. Max and Bigger’s conversations allowed Bigger to understand some facets of communism. Their conversations also opened Bigger, with Bigger appreciating Max’s efforts in unraveling him. Max made Bigger feel like an individual. Toward the end, Bigger achieves a clarity that allows him to approach his mortality with more dignity.

Native Son is, without a doubt, a literary classic. Through the story and fate of Bigger Thomas, the novel vividly captures the African American experience. They had to deal with oppression from people who treated them as less than their equals mainly because of the color of their skin. They were seen as incapable of helping themselves. The novel captured the impact of racism on both the oppressor and the oppressed. Both sides cried foul but it was palpable how power, social, political, and economic dynamics careen heavily toward one side of the spectrum. Justice also serves one side of the spectrum. These are conditions, unfortunately, that persist in the contemporary. Racism and discrimination are corrosive elements of modern American society. While there are major developments in the right direction, it is still evident how power dynamics and privilege favor one skin color. These conditions underline the continuing relevance of Wright’s magnum opus. A story of character development and moral and social justice, an extensive socio-political and socioeconomic commentary, Native Son is a modern literary classic that transcends both time and physical boundaries.

With a supreme act of will springing from the essence of his being, he turned away from his life and the long train of disastrous consequences that had flowed from it and looked wistfully upon the dark face of ancient waters upon which some spirit had breathed and created him, the dark face of the waters from which he had been first made in the image of a man with a man’s obscure need and urge; feeling that he wanted to sink back into those waters and rest eternally.

Richard Wright, Native Son

Book Specs

Author: Richard Wright

Publisher: Perennial Classics

Publishing Date: 1998 (1940)

No. of Pages: 462

Genre: Literary, Historical

Synopsis

Right from the start, Bigger Thomas had been headed for jail. It could have been for assault or petty larceny; by chance, it was for murder and rape. Native Son tells the story of this young black man caught in a downward spiral after he kills a young white woman in a brief moment of panic. Set in Chicago in the 1930s, Wright’s powerful novel is an unsparing reflection of the poverty and feelings of hopelessness experienced by people in inner cities across the country and of what it means to be black in America.

About the Author

Richard Nathaniel Wright was born on September 4, 1908, near Natchez, Mississippi, U.S. to an illiterate sharecropper and a schoolteacher. His father abandoned the family when Wright was still five. Wright spent time in the orphanage before moving with his mother to Jackson where he was raised in part by his strict Seventh Day Adventist grandparents. He grew up in poverty. He dropped out of high school to work odd jobs before moving northward as part of the Great Migration, first to Memphis, Tennessee, and eventually to Chicago. In 1932 Wright became a member of the Communist Party. Wright eventually left the party in 1944 due to political and personal differences.

Because of their poverty, books were not allowed in the house Wright grew up in. Nevertheless, Wright harbored his dream of becoming a writer in secret. In Chicago, after working in unskilled jobs, he got an opportunity to write through the Federal Writers’ Project. In 1937, he went to New York City where he became the Harlem editor of the Communist Daily Worker and coeditor of Left Front. In the latter, Wright published some of his earlier poems. However, it was through his short story collection Uncle Tom’s Children (1938) that he gained attention for his writing. He built on this momentum and published what many considered his magnum opus, Native Son, in 1940. The book was a literary sensation. A year after its publication, it was staged successfully as a play on Broadway in 1941 directed by Orson Welles. It was also adapted into a film in Argentina in 1951; Wright himself played Bigger Thomas. The book established Wright as a major literary force in the Black Arts Movement. During the 1940s, Wright wrote a sociological account of the Great Migration, 12 Million Black Voices (1941), with photographs collected by Edwin Rosskam. Five years after the success of Native Son, Wright published Black Boy a moving account of his childhood and young manhood in the South.

Wright moved to France permanently in 1947. This move was driven by the racism he experienced in the United States. In the 1950s, he spent time in Ghana working on African liberation movements. Among his later works include The Outsider (1953), Black Power (1954), The Color Curtain (1956), the collected lectures White Man, Listen! (1957), and The Long Dream (1958). Wright also wrote poems and had even written roughly 40,000 haikus. These haikus were collectively published in the volume Haiku: This Other World (1998, republished as Haiku: The Last Poems of Richard Wright in 2012). Some of Wright’s works were published posthumously, such as Eight Men (1961), American Hunger (1977), and Rite of Passage (1994).

Wright passed away on November 28, 1960, in Paris, France due to a heart attack.