Of the Dispossessed

The Nobel Prize in Literature—long regarded as the apex of global literary recognition—has historically elevated writers whose bodies of work had previously escaped broad international attention. Alongside predictable laureates such as John Steinbeck, Rabindranath Tagore, Toni Morrison, Gabriel García Márquez, Ernest Hemingway, and Pablo Neruda, the Swedish Academy has also selected less anticipated figures. Abdulrazak Gurnah’s 2021 win exemplifies this latter trend. Before the announcement, Gurnah had occupied a marginal place in public speculation; pundits and betting agencies positioned him well below perennial contenders, including Haruki Murakami, Salman Rushdie, Annie Ernaux, Margaret Atwood, and Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, the latter of whom had once been his professor.

Gurnah’s recognition was, nevertheless, a welcome announcement. It was a monumental moment, making him only the fifth African writer (or sixth, with the inclusion of Doris Lessing) to be recognized by the Swedish Academy. He is also the first Black writer to receive the honor since Toni Morrison in 1993. Born on December 20, 1948, in Zanzibar, Gurnah was forced to flee his homeland at just 18 years old. After Tanzania declared independence from British rule, Zanzibar was swept by a revolution, and citizens of Arab origin were persecuted and oppressed. Gurnah settled in England as a refugee, eventually gaining British citizenship. However, he maintained close ties with his homeland, which would become the cradle of most of his works. Working first as an academic, he made his literary debut in 1987 with the publication of Memory of Departure. The rest, as they say, is history.

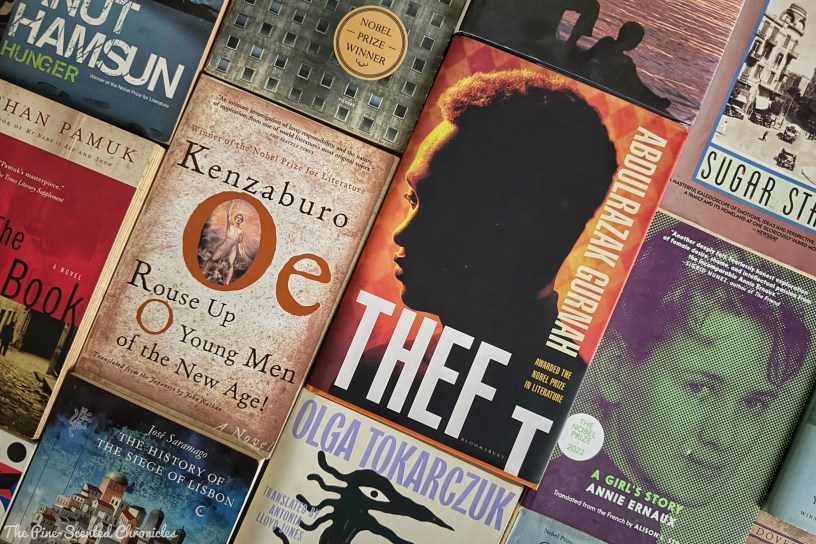

Remaining true to his roots, Gurnah has chronicled the checkered history of his homeland, vividly exploring the historical and social transformations that swept East Africa, particularly the decades immediately before and after Tanzania’s independence. In selecting Gurnah, the Swedish Academy commended him “for his uncompromising and compassionate penetration of the effects of colonialism and the fate of the refugee in the gulf between cultures and continents.” Exploring the legacy of his provenance and the complexities of living through a transitional period, this was an apt description of the literary legacy Gurnah has accreted since his debut. Building on the successes of his earlier works, Gurnah made his long-awaited literary comeback in 2025 with Theft, his eleventh novel and his first major publication since his Nobel Prize recognition.

It was later, when she was in her old bed in the dark, that the shock of it sank in. He was gone, and she was on her own with the child. She would never find happiness again. There was a pain sitting like a lump in her chest, a proper presence, and an anxious charge like a current through her limbs. Her ears hummed as she lay trembling in the dark, and for the first time in that long day her tears flowed. It felt as if love had fled from her forever.

~ Abdulrazak Gurnah, Theft

A writer renowned for looking back, Gurnah once again returns to Zanzibar, the cradle of his birth. Spanning the late 1980s to the early 2000s, the story begins with Raya, a young woman from the rural village of Unguja, just off the coast of Tanzania. She was hastily and miserably married off to a much older man, Bakari Abbas. Having suffered under her husband’s cruelty, Raya plotted her escape. She pretended to visit her home, where she abandoned her three-year-old son, Karim, to her parents’ care. Raya fled to Dar es Salaam, then the nation’s capital, where she remarried Haji. Meanwhile, Karim—one of the novel’s three major characters—was raised by a stepbrother who nurtured his academic inclinations. He pushed Karim to pursue his ambition of attending university, and Karim eventually earned a scholarship to study in the city. When he became an adult, he secured a government job overseeing environmental initiatives in Zanzibar.

Despite his mother’s abandonment, Karim and Raya kept in touch. When he attended university, he moved into his mother’s affluent household, where he got on well with his stepfather. It was in this household that his path crossed with Badar, the family’s domestic servant. The second of the novel’s three major characters, Badar was raised in the countryside by a surrogate family. However, at thirteen, he was abandoned by them. Due to his hormonal pubescent changes, he had begun causing trouble in the household; his surrogate sister even accused him of eyeing her while she washed. Like other orphans, Badar grew up with no knowledge of his real parents. His mother perished during a cholera epidemic when he was younger, and no one knows what happened to his father. Despite his absence, Badar’s father looms large in his story, as Badar’s removal from his home and his subsequent position as a live-in servant stem from his father’s actions.

Badar was then deposited in the house of the wealthy Uncle Othman, Haji’s father. Due to his youth, Badar arrived in the city unaware of his station in life. He was initially treated well and even struck up a friendship with Karim. The novel progresses by charting their intertwined destinies yet diverging circumstances. The crux of the story occurs when Badar is wrongly accused of theft—hence the book’s title. Just when he had found stability, it was disrupted by the false accusation. It was eventually revealed that Ismail, Badar’s father, was related to Haji. Ismail had also stolen from Uncle Othman, thus fueling Othman’s resentment toward Badar. Badar’s saving grace came in the form of his protective friendship with Karim. When Badar was about to be thrown into the street as punishment for his supposed theft, Karim took him under his wing. It was also through Karim that Badar found employment in a hotel.

A third prominent character is Fauzia, who was born with a mild epileptic condition. Because of her affliction, her parents worried about her marital prospects. Their fears were assuaged when Karim married her after graduating from university. Like Karim and Badar, she was born and raised in the countryside. She moved to the city filled with hope. She aspired to be a teacher, a profession in which she eventually found success. It was there that her path converged with Karim’s and Badar’s, with Karim and Fauzia treating Badar as their younger sibling. However, Fauzia’s condition loomed over her married life. She was afraid of transmitting her illness to her offspring. She eventually fell pregnant and gave birth to a girl named Nasra. This was another pivotal moment, as it exposed the fault lines beneath the surface of their relationships.

When he was alone on the mat in the storeroom that night, closed in and in the dark, he felt a panic cutting through his misery. He sat up in alarm and heaved for air. He was too old for sobbing in the dark, but he could not stop. After what seemed a long time, the nausea eased, and he stretched out on the floor mat and tried to sleep. He remembered his father sitting silent and sullen on the bus, then striding in front of him past the blue mosque. He remembered his look of rage, his last words to him.

~ Abdulrazak Gurnah, Theft

Theft is an expansive novel that oscillates across various periods. Its polyphonic perspectives and diverse characters broaden the narrative focus. On the surface, it explores the unlikely friendship among three individuals from vastly different circumstances. Their varied backgrounds provide the story with depth and nuance. Badar, Karim, and Fauzia are individually complex and compelling characters, each imbued with their own dreams. Their complex bond provides a lush mantle upon which the rest of the story is skillfully built. As the three protagonists move from adolescence to adulthood, their story traces their growth and development. Their friendship—like any other—was tested and influenced by outside pressures and temptations. Their growing bond forms one of the novel’s most affectionate facets, especially as they also had to transcend stark social-class divisions. However, betrayal is rife and carries irreversible consequences that alter their lives and the lives of those around them. Their lives inevitably intertwine, diverge, and reconnect.

Theft, however, is not merely an exploration of friendship. An important detail is the backdrop against which their stories unfold. As they navigate the complexities of relationships, they are also grappling with the turbulent legacy of colonialism. Unlike the characters in Gurnah’s earlier works—such as Paradise and, more recently, Afterlives—the trio in Theft never personally experienced the violence that culminated in Tanzania’s independence. Nevertheless, their lives are profoundly affected by the aftermath of this pivotal historical event. Gurnah offers no preamble in his depiction of the sociopolitical atmosphere in postcolonial Tanzania, opening the novel with vivid descriptions of contemporary life in his homeland. The novel’s temporal and structural expansiveness also allows Gurnah to situate personal histories within broader political and historical contexts. References to the Umma Party, Cuban training missions, and even the Srebrenica massacre embed the narrative within transnational histories of conflict and ideological realignment.

While historical context is significant, the characters’ lives are overshadowed by Tanzania’s colonial heritage. The residues of Tanzania—and particularly Zanzibar’s—colonial history manifest in the personal and familial conflicts the characters experience later in life. These conflicts result in psychological displacement. Each of them encounters rejection and struggles during their formative years. Karim and Badar, for instance, are haunted by the absence of their parents. Meanwhile, the older generations are either resigned to their fate or deeply embittered. Most have learned to bear their struggles without complaint, silently lamenting the changes sweeping Africa. Some grieve for what the younger generation will endure in their struggle for freedom. The legacy of the violent past is also vividly portrayed through Fauzia’s mother, who is plagued by anxiety. She often complains of “footsteps on the stairs no one else heard, voices in the street at night—which to her meant armed robbers—shortages, violence, the brutality of the world.”

As the story moves forward, the titular theft takes on a broader meaning. The false accusation of theft against Badar is a catalyst, driven by malice and by past actions beyond his control. By extension, Badar is stolen from his roots; stories of young men taken from their villages and forced into servitude to fulfill past obligations are ubiquitous in Gurnah’s oeuvre. The psychological and emotional displacement the characters experience is also a form of theft. The broader theft lies in how the colonists stripped the locals of liberty. Beyond material loss, theft in the novel encompasses the broader implications of cultural appropriation and the theft of identity. The characters strive to reclaim the personal and cultural identities they lost amid sweeping societal changes. The novel’s concept of ownership transcends physical possession, delving into both personal and political exile.

She learned to make it easier for herself, to evade pain by preparing her body to receive him. She learned to acquire some control so she was not always at his mercy, to delay and postpone, and to feign enjoyment. She said no when she could, and fought back when he rebuked her, returning vicious abuse to his hectoring threats. It was a nightmare she could not tell anyone about.

~ Abdulrazak Gurnah, Theft

In tackling the complexities of relationships, Gurnah also explores the dynamics of marital life, particularly through Karim and Fauzia. In stark contrast to the bliss of their courtship, their marriage is riddled with challenges. Fauzia’s fear of transmitting her condition to her child looms over their relationship. As the couple grapples with the rigors of marriage, Fauzia must also contend with postpartum depression and the demands of raising a newborn. The novel also explores the feminine struggle within patriarchal African culture. African women’s voices are often muted, and their fates are determined for them. Raya’s marriage to an older man, arranged against her wishes, exemplifies this. Initially, she is unable to escape the abusive marriage; the fear of being ostracized by her family and society weighs heavily on her. These familiar societal expectations also weigh on Fauzia. Notably, compared with Gurnah’s other works, the female characters are more central to the action.

Yet in dark times, strength breaks through; Gurnah’s female characters are fully developed and nuanced. Raya finds the courage to flee marital abuse, albeit at a steep price: abandoning her son. In walking away, she chooses humiliation and social stigma, but the decision ultimately makes her stronger. Fauzia, too, finds a way to thrive despite societal expectations. Subtly, the novel also examines the impact of tourism on contemporary Zanzibar and Tanzania. In many African and Gulf countries, the lifeblood of the hospitality industry consists of waiters, servants, and other service staff. Through Badar’s experience, Gurnah sheds light on the conditions such workers face. They are always seen through the eyes of their employers. Badar, for instance, is constantly watched by the Mistress: “The Mistress kept an eye on him to make sure he did everything right, but she didn’t scold him when he made a mistake.” The prevalence of tourism also nods to the region’s rapid modernization.

Gurnah’s characterization remains one of the novel’s central strengths. Individually, they add depth and nuance to the story. Their struggles and triumphs provide texture, and their growth forms the backbone of the novel. Badar emerges as the novel’s emotional core, yet he is ironically the most stagnant. Gurnah crafts him as the character who most easily earns readers’ sympathy. He is the one we root for to achieve the transformation that would grant him agency over his life. His circumstances obscure from him how society views him. He is a victim—a fact he does not fully recognize. This contributes to his aversion to change. His arc, marked by both vulnerability and acceptance, reveals Gurnah’s sustained interest in the ethical and psychological dimensions of dispossession.

Theft reinforces the ideas, themes, and subjects Gurnah explored in his earlier works. Zanzibar and Tanzania remain the mantle upon which his lush narratives are juxtaposed. Set in a more contemporary period, Theft grapples with Tanzania’s colonial history, inevitable modernization, and, subtly, the shift toward capitalism, while examining the legacy of colonialism in the country’s generational identity. Karim, Fauzia, and Badar are individually compelling characters with equally propulsive stories. Their narratives explore the societal fault lines and moral complexities plaguing modern Tanzania. They contend with alienation and the displacement experienced by those perceived as outsiders. They remain tethered to their past, yet they embody a nation slowly rousing from its wounds and moving toward its future. Theft is also a vivid story about finding one’s place. While it is not a radical departure from Gurnah’s earlier works, it is a welcome addition to his tradition of capturing postcolonial struggles and resistance.

Some things seem predictable after they have happened, when before they might have seemed unlikely. He was gone, and it was as if she had known he would be. He was gone, and when he came back, if he came back, she would not be there. She did not want to speak to anyone, not yet. She sat on the sofa, the sun streaming in through the window behind her, considering how to proceed, contemplating what she could retrieve from the wreckage of her life. In her own heart, she had started to suspect that love was ailing some time ago, but she had not known that it would come to this so swiftly.

~ Abdulrazak Gurnah, Theft

Book Specs

Author: Abdulrazak Gurnah

Publisher: Bloomsbury Publishing

Publishing Date: 2025

Number of Pages: 246

Genre: Historical, Literary

Synopsis

What are we given, and what do we have to take for ourselves?

It is the 1990s. Growing up in Zanzibar, three very different young people – Karim, Fauzia and Badar – are coming of age, and dreaming of great possibilities in their young nation. But for Badar, an uneducated servant boy who has never known his parents, it seems as if all doors are closed.

Brought into a lowly position in a great house in Dar es Salaam, Badar finds the first true home of his life – and the friendship of Karim, the young man of the house. Even when a shattering false accusation sees Badar sent away, Karim and Fauzia refuse to turn away from their friend.

But as the three of them take their first steps in love, infatuation, work and parenthood, their bond is tested – and Karim is tempted into a betrayal that will change all of their lives forever.

About the Author

To learn more about the awardee of the 2021 Nobel Prize in Literature, Abdulrazak Gurnah, click here.