The Anti-Conspiracy Theory Novel

One of the most influential and extensive literary traditions in the world, Italian literature has, over the centuries, crafted a legacy that transcends time. Its rich tradition traces its beginnings to the 13th century, when it branched out from the predominantly Latin body of work that defined European literature during the Middle Ages. Like most literatures of that period, the earliest works of Italian literature were written by authors trained in ecclesiastical schools. Over the succeeding centuries, Italian literature evolved, slowly establishing itself as a premier literary tradition. Its long history of literary excellence began with the successes of highly regarded writers such as Giovanni Boccaccio, Niccolò Machiavelli, and Dante Alighieri. Their works—Boccaccio’s Decamerone, Machiavelli’s Il Principe (The Prince), and Alighieri’s Comedìa (The Divine Comedy)—were literary sensations. These masterpieces have transcended time and geographical boundaries and remain hallmarks of Italian literature, retaining their relevance in literary discourse.

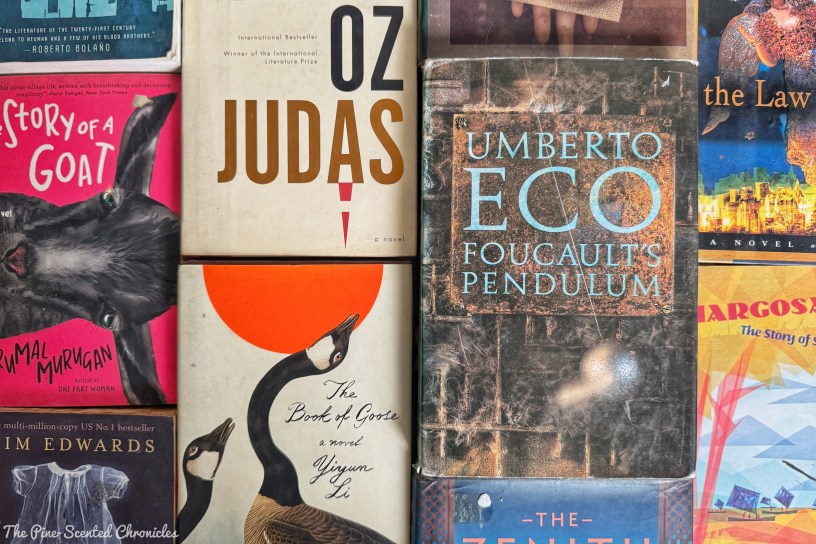

Over time, Italian literature grew even more prominent, driven by the rise of writers such as Italo Calvino, Primo Levi, Oriana Fallaci, and Nobel Laureate Dario Fo. Their contemporary, Umberto Eco (1932–2016), also rose through the ranks to become one of the most recognized Italian writers. Interestingly, before pursuing a literary career, Eco undertook a variety of vocations, including cultural editor, lecturer, and academic. His initial studies focused on aesthetics before branching into communication and semiotics. He was already a renowned semiotician before becoming a highly celebrated novelist. Nearly fifty years old when he published his major novel Il nome della rosa (1980; The Name of the Rose), Eco achieved instant literary success. The novel elevated his reputation and established him as a household name. Il nome della rosa remains one of the most widely recognized literary titles, a testament to its status as a timeless classic of Italian literature.

Building on the success of Il nome della rosa, Eco published his sophomore novel, Il pendolo di Foucault, in 1988. Like its predecessor, it was a critical success and, a year after its Italian publication, became available to Anglophone readers as Foucault’s Pendulum. The titular pendulum was invented by Jean-Bernard-Léon Foucault (1819–1868) and swings in the Conservatoire des Arts et Métiers in Paris. Demonstrating the Earth’s rotation, the concept was introduced to Eco by Mario Salvadori, a professor of civil engineering and architecture at Columbia University. While the pendulum swings harmlessly enough, under Eco’s scrutinizing gaze, it transforms into something far more sinister. Unlike his debut novel, which was set in medieval times, Foucault’s Pendulum takes place in the contemporary period. Nevertheless, Eco employs the same pattern of linguistic play and narrative proliferation that characterized his earlier work.

I should be at peace. I have understood. Don’t some say that peace comes when you understand? I have understood. I should be at peace. Who said that peace derives from the contemplation of order, order understood, enjoyed, realized without residuum, in joy and triumph, the end of effort? All is clear, limpid; the eye rests on the whole and on the parts and sees how the parts have conspired to make the whole; it perceives the center where the lymph flows, the breath, the root of the whys…

~ Umberto Eco, Foucault’s Pendulum

Serving as a narrative focal point is Casaubon, one of the novel’s three central characters. When the story begins, he is hiding in the Conservatoire des Arts et Métiers, surrounded by relics of technological progress such as engines and aircraft. He waits for midnight, believing that an occult group will converge at the museum at the stroke of midnight during the summer solstice. Casaubon firmly believes that this secret group is responsible for the disappearance of his friend and colleague, Jacopo Belbo. Before arriving in Paris, Casaubon received a frantic call from Belbo, who claimed he was being pursued by the Knights Templar because of his knowledge of a secret Plan. As Casaubon searches for his friend, he deciphers the encrypted files Belbo left behind and begins to suspect that the occult group is also pursuing him. As the narrative unfolds, questions about the circumstances leading to Casaubon’s present situation come to the forefront: Who is Casaubon? What is the secret Plan that led to Belbo’s disappearance?

As is often the case, the answers lie in the past. While waiting for midnight as the pendulum continues to swing, Casaubon reflects on the twists and turns of his life, particularly the previous twelve years. The narrative flashes back to 1970s Milan, where Casaubon was a doctoral student in philology writing a thesis on the Knights Templar while also participating in political protests, including the 1968 Italian uprising. In a Milan tavern crowded with students and intellectuals of differing political views, Casaubon was approached by Belbo, a scientific editor at the publishing house of Mr. Garamond. Belbo was assisted by his associate, Diotallevi, a Jewish cabalist and editor. Belbo invited Casaubon to review a manuscript on the Templars written by retired Army Colonel Ardenti, who claimed to have deciphered a coded message detailing a plot engineered by the Knights Templar. Ardenti asserted that the Templars still existed and had devised a plan for world domination involving the deployment of telluric energy—the fundamental power of the Earth, named after the Roman earth goddess Tellus.

The Colonel believed the Templars intended to activate their plan in 1944; however, the project appeared to have been postponed indefinitely. These inconsistencies—along with Ardenti’s belief that the Templars guarded a radioactive Holy Grail—made the editors skeptical of his claims. Initially dismissing him as delusional, they nevertheless agreed to meet with him. After the meeting, the Colonel mysteriously vanished. Drawn into the ensuing investigation, Casaubon and Belbo were informed by an official that an occult member interested in Ardenti’s work may have been involved. The incident left a bitter aftertaste, ultimately leading to a divergence in the trio’s paths. After completing his studies, Casaubon moved to Brazil to teach Italian. Following the dissolution of his relationship with Amparo, a captivating local woman, he returned to Florence in the late 1970s. Struggling to find academic employment, he shifted toward literary research.

Casaubon eventually returned to Milan, where he was employed by Mr. Garamond and reunited with Belbo and Diotallevi. With Garamond’s encouragement, the trio ventured into vanity publishing, discovering it to be a lucrative enterprise. Numerous incompetent writers aspired to publish conspiracy theories, even at great personal expense. Garamond operated Manutius, a vanity press, and the friends’ interest in such publications was fueled by their shared fascination with esoteric and occult knowledge. Immersed in occult manuscripts, the three devised an elaborate intellectual game called “the Plan,” drawing on their extensive knowledge of obscure topics. What began as a harmless exercise borrowed logical fallacies and references from conspiracy theorists. Using Abulafia, Belbo’s word processor, they cross-referenced their ideas, which Abulafia synthesized into something seemingly coherent and convincing.

If what you saw has anything in common with the Masons, it’s the fact that Bramanti’s rite is also a pastime for provincial politicians and professional men. It was thus from the beginning: Freemasonry was a weak exploitation of the Templar legend. And this is the caricature of a caricature. Except that those gentlemen take it extremely seriously. Alas! The world is teeming with Rosicrucians and Templars like the ones you saw this evening. You mustn’t expect any revelation from them, though among their number occasionally you can come across an initiate worthy of trust.

~ Umberto Eco, Foucault’s Pendulum

Foucault’s Pendulum captivates readers with its dense infusion of hermetic thought. The editors connect historical events, philosophical theories, secret societies, and mystical beliefs spanning centuries. Added to this mix are conspiracy theories involving figures such as the Comte de Saint-Germain, an allegedly immortal man. Notably, Amparo introduces Casaubon to Agliè, an elderly man claiming to be the mystical Comte himself. As time ticks on, the narrative progresses slowly, while Eco regales readers with discussions of esoteric subjects ranging from the Solar Myth of the Great Pyramid and African mythology to Brazilian voodoo. The world, Eco suggests, teems with conspiracies proposed by conspiracy hunters from every walk of life, from ordinary individuals to devout religious figures.

Conspiracies often involve organizations, ranging from the mundane to the obscure. Among the most frequent subjects of conspiracy theories are institutions such as the CIA and the Russian KGB, both referenced in the novel. The Catholic Church itself is fertile ground for conspiratorial thinking. Mr. Garamond even categorizes the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (the Mormons) as an “occult” organization worth contacting for publishing ideas. The novel also references the Assassins of Alamut, the Bavarian Illuminati, Candomblé, the fictional Cthulhu cult, Freemasons, Gnostics, Opus Dei, and the Rosicrucians. The editors are eventually invited to attend a Rosicrucian ritual at a secluded villa, where they witness arcane rites that both fascinate and disturb them. Gradually, they construct an elaborate mythic narrative centered on the Knights Templar, a papal order founded in the 12th century and officially disbanded in the 14th century.

Eventually and inevitably, the editors become convinced that a grand conspiracy—one synthesizing all others—is underway. This underscores the blurring of the lines between fiction and reality. What began as an innocuous intellectual game evolves into something darker as they start believing the Plan is real. The editors became so engrossed in the idea of the Plan that it started dictating their lives. In concocting this grand narrative, they unwittingly summon forces beyond their control. The novel highlights the allure of conspiracy theories and humanity’s inclination toward them. Often unnoticed, these conspiracy theories permeate everyday life. Many of us are drawn toward them and even let them shape our own lines of thought. This tendency eventually develops into an obsession, as is the case with the editors. There is danger in obsessing over conspiracy theories, as they soon foster paranoia.

Through its exploration of conspiracies and underground organizations, Eco was also subtly examining the very nature of history and memory. History is shaped by diverse perspectives, allowing for multiple interpretations. Ambiguity is inevitable. After all, history is written by the victors. Such gaps invite speculation, often filled by conspiratorial thinking. The characters also have different understandings of history. Eco contrasts medieval history with events from the late 1960s through the 1980s, illustrating how generational differences shape historical understanding. Casaubon was more critical of present-day events, reflecting on the political and social radicals of his time. Belbo, on the other hand, dismisses the younger generation’s activism. He deems it as initially filled with “enthusiasm, courage, self-criticism.” He also believes that these movements only inspired more violence, cowardice, and self-indulgence.

We usually believe that the tamer is attacked by the lion and that the tamer stops his attack by raising his whip or firing a blank. Wrong: the lion was fed and sedated before it entered the cage and doesn’t feel like attacking anybody. Like all animals, it has its own space; if you don’t invade that space, the lion remains calm. When the tamer steps forward, invading it, the lion roars; the tamer then raises his whip, but also takes a step backward (as if in expectation of a charge), whereupon the lion calms down.

~ Umberto Eco, Foucault’s Pendulum

In Foucault’s Pendulum, symbols and hidden messages abound. It comes with the territory; Eco is, after all, a professor of semiotics. His mastery of codes, signs, and hidden meanings resonates across the novel, tickling the imagination and inviting readers to draw their own conclusions. However, the novel ultimately subverts the traditional mystery fiction genre. As the story progresses, it transforms into an anti-conspiracy theory narrative that deconstructs the conspiratorial thinking itself. The novel serves as a subtle critique of conspiracies often woven into postmodern literature. While the intricacies of the Plan dominate the plot, the emotional core lies in the characters’ development as they transition from skeptical editors who ridiculed the Manutius manuscripts into Diabolicals—self-financing occult writers—themselves.

Eco explores humanity’s obsession with conspiracy theories. Eco postulates that this is a manifestation of our need for meaning and certainty. Through the editors, Eco examines this human tendency to seek patterns and connections despite overwhelming evidence to the contrary. Each of the main characters is in search of meaning in their lives. Diotallevi has devoted his life to the study of the Torah, searching for meaning in this religious text. Belbo was constantly searching for meaning, even in the unlikeliest places. His quest was for inner peace, but he only found meaning in the Plan. Meanwhile, Casaubon was looking for meaning throughout the novel, underscoring his scholarly endeavors. He would eventually find meaning with his partner, Lia, and their son, Giulio—only to abandon them in pursuit of the illusory significance of the Plan.

Following a tragedy, Casaubon experiences a moment of enlightenment: it was the search for meaning that led them astray. Their search for meaning led them to look for meaning where there is none. They ignored the meaning that was right in front of them. Serving as the antithesis to the three conspiracy-obsessed men was Lia. Practical and maternal, she was the voice of reason who reminded Casaubon of a profound reality that they had overlooked. Meaning is found not in hidden messages, but in the mere act of living, in the body, and in love. This is a simple but deep message that resonates on a universal scale. Lia also serves as a reminder of the dangers of conspiracy theories. They can serve as distractions from the real work of human existence. The novel thus serves as a cautionary tale about unchecked pattern-seeking and humanity’s relentless quest for meaning.

Foucault’s Pendulum takes the readers on a literary roller coaster ride. History, symbolisms, and conspiracies converge in a lush tapestry capably woven together by Eco. It is an encyclopedic detective novel that evolves from a playful exploration of conspiracy theories into a meditation on the dangers of excessive knowledge and interpretation. Dense with symbols and layered narratives—hallmarks of Eco’s oeuvre and echoes of his vocation—it challenges readers while warning against intellectual hubris. It is a caveat against men’s insatiable desire to search for meaning and connection, while underscoring the dangers associated with open interpretation. Open interpretations often lead to a chaotic and unworkable reality. Though demanding, Foucault’s Pendulum rewards careful reading and stands as a testament to Eco’s ambition and innovation as one of the world’s most influential writers.

Not that the incredulous person doesn’t believe in anything. It’s just that he doesn’t believe in everything. Or he believes in one thing at a time. He believes a second thing only if it somehow follows from the first thing. He is nearsighted and methodical, avoiding wide horizons. If two things don’t fit, but you believe both of them, thinking that somewhere, hidden, there must be a third thing that connects them, that’s credulity.

~ Umberto Eco, Foucault’s Pendulum

Book Specs

Author: Umberto Eco

Translator (from Italian) William Weaver

Publisher: Guild Publishing

Publishing Date: 1989 (1988)

Number of Pages: 641

Genre: Literary, Mystery Thriller, Speculative

Synopsis

Foucault’s Pendulum is a superb entertainment by the author of The Name of the Rose. An enthralling mystery, a sophisticated thriller, a breathtaking journey through the world of ideas and aberrations, the treasures and traps of knowledge, Umberto Eco’s new novel will delight, tease, provoke, and stimulate.

One Colonel Ardenti, who has unnaturally black brilliantined hair, an Adolphe Menjou mustache, wears maroon socks and fought in the Foreign Legion, starts it all. He tells three editors at a Milan publishing house that he has discovered a coded message about a Templar plan, centuries old and of diabolical complexity, to tap a mystic source of power greater than atomic energy.

The editors (who have spent altogether too much time rewriting crackpot manuscripts on the occult by self-subsidizing poetasters and dilettantes) decide to have a little fun. They’ll make a plan of their own. But how?

Randomly they throw in manuscript pages on hermetic thought. The Masters of the World, who live beneath the earth. The Comte de Saint-Germain, who lives forever. The secrets of the solar system contained in the measurements of the Great Pyramid. The Satanic initiation rites of the Knights of the Temple. Assassins, Rosicrucians, Brazilian voodoo. They feed this all into their computer, which is named Abulafia (Abu for short) after the medieval Jewish cabalist.

A terrific joke, they think – until people begin to disappear mysteriously, one by one, starting with Colonel Ardenti.

About the Author

To learn more about the renowned Italian writer, click here.

I was the type who looked at discussions of What Is Truth only with a view toward correcting the manuscript. If you were to quote “I am that I am,” for example, I thought that the fundamental problem was where to put the comma, inside the quotation marks or outside.

~ Umberto Eco, Foucault’s Pendulum